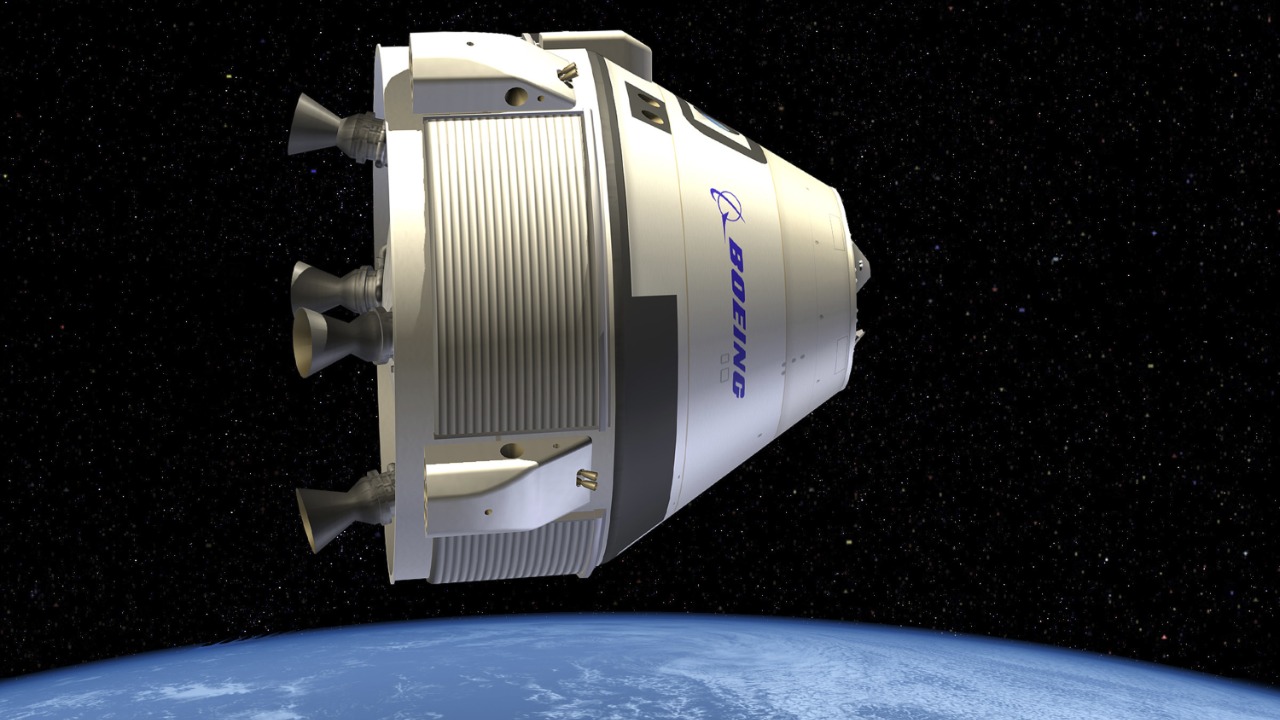

Boeing’s CST-100 Starliner is getting a reset. Instead of rushing back to crewed operations after its troubled astronaut test, the spacecraft is now slated to fly uncrewed in April 2026, carrying only cargo to the International Space Station and serving as a high-stakes systems check rather than a passenger flight. That shift marks a pivotal moment for NASA’s Commercial Crew Program, signaling both a loss of confidence in Starliner’s near-term role and a pragmatic attempt to salvage value from a vehicle that has yet to meet its original promise.

The new plan reframes Starliner as a workhorse in training, not yet a peer to SpaceX’s Crew Dragon, and it forces NASA and Boeing to rethink what success looks like for a program that was supposed to deliver routine astronaut transport. I see this as a strategic retreat designed to buy time, gather data, and keep options open, even as it underscores how far the spacecraft still has to go before it can be trusted with human lives again.

Starliner’s next mission: cargo only, no astronauts on board

The most immediate change is stark: the next Starliner flight, targeted for April 2026, will launch without astronauts and will be limited to cargo. Instead of ferrying a crew, the CST-100 capsule will be used to deliver supplies and equipment to the International Space Station, with NASA explicitly restricting the mission to uncrewed operations. The agency has confirmed that Boeing’s CST-100 Starliner spacecraft is now cleared to carry only cargo on its upcoming flight, a decision that caps months of internal debate about whether the vehicle was ready to return people to orbit after its fumbled astronaut outing, and that shift is reflected in the way NASA described the mission profile in its own statement and in coverage that noted how Boeing’s CST-100 Starliner spacecraft will be used.

By stripping out the crew, NASA is effectively turning this flight into a full-scale systems test under real orbital conditions, with the added benefit of resupplying the station. The cargo-only configuration allows engineers to stress Starliner’s propulsion, guidance, and docking systems without the added risk of human passengers, and it gives mission planners more flexibility to respond to anomalies during ascent, rendezvous, or reentry. It is a conservative posture that acknowledges the spacecraft’s recent problems while still leveraging its capabilities to support the orbital laboratory, and it sets the tone for how the program will be judged over the next several years.

How a “fumbled” astronaut flight reshaped NASA’s plans

The decision to keep astronauts off the next Starliner flight did not come out of nowhere. It follows what NASA itself has characterized as a fumbled astronaut mission, a crewed test that exposed weaknesses in the spacecraft’s systems and in Boeing’s readiness to operate it as a reliable human transport. In the wake of that experience, NASA said the next Starliner mission would not carry people, a clear acknowledgment that the agency was not satisfied with the performance it saw and that it needed to scale back expectations for how quickly the vehicle could be certified for routine crew rotation, a reality captured in reporting that described how NASA and Boeing Scale Back Starliner Missions After Fumbled Astronaut Flight.

That crewed outing was supposed to be a capstone demonstration, the moment when Boeing proved it could stand shoulder to shoulder with SpaceX in flying astronauts safely to orbit. Instead, it became a turning point that forced NASA to rethink how much risk it was willing to accept and how much additional testing Starliner would need before it could be trusted as a regular ride for its crews. The fallout from that mission is now baked into the new flight plan, with the agency explicitly repositioning the next launch as a cargo-only operation and signaling to Congress, the White House, and the broader space community that it is prioritizing safety and reliability over schedule pressure, even as it continues to rely on other vehicles to keep astronauts moving to and from the station.

A temporary demotion to gather hard data

In practical terms, the cargo-only mission amounts to a temporary demotion for Starliner, a step down from crew transport to a more limited but still critical role. NASA and Boeing have agreed to rethink the spacecraft’s place in the Commercial Crew lineup, treating the upcoming flight as an end-to-end test that can validate recent propulsion updates, new thruster redundancy strategies, and other technical changes that were introduced after the troubled astronaut outing. This repositioning has been described as a way to gather data from comprehensive tests of those propulsion updates and thruster redundancy improvements, with NASA and Boeing explicitly agreeing to rethink the Starliner spacecraft’s role so they can better understand how it performs under real mission conditions, a shift captured in coverage that noted how NASA and Boeing have agreed to rethink the Starliner spacecraft.

I see this as a classic engineering move: when a system underperforms in a high-stakes environment, you pull it back, simplify the mission objectives, and use the next flight to instrument everything you can. By flying uncrewed, Starliner can be pushed harder in certain regimes, with more aggressive testing of its propulsion and redundancy schemes than would be acceptable on a human-rated mission. The data from that flight will feed directly into decisions about whether the vehicle can eventually return to carrying astronauts or whether its long-term future lies in cargo and specialty roles, a question that will hang over the program until those numbers are in and fully analyzed.

Contract changes and a narrower role in Commercial Crew

The shift to an uncrewed cargo mission is not just an operational tweak, it is now embedded in the formal relationship between NASA and Boeing. The agency has modified its Commercial Crew contract to reflect Starliner’s new trajectory, designating the next flight, known as Starliner-1, as a mission that will be used to deliver necessary cargo to the orbital laboratory rather than to rotate a crew. In its own description of the updated agreement, NASA made clear that certification of Boeing’s Starliner remains a goal, but it also spelled out that Starliner-1 will be focused on cargo delivery to the International Space Station, a change that is explicitly laid out in the agency’s explanation of how NASA, Boeing modify Commercial Crew contract.

By rewriting the contract, NASA is doing more than adjusting a single mission profile, it is narrowing Starliner’s official role in the near term and giving itself more flexibility to rely on other vehicles for astronaut transport. The updated language effectively decouples Starliner-1 from the original expectation that it would be a crew rotation flight, and it signals to Boeing that future crewed missions will depend on how convincingly the company can demonstrate reliability and safety in this new cargo-focused phase. For Boeing, that means the April 2026 mission is not just a technical test but a contractual proving ground, one that will influence how many additional flights NASA is willing to buy and what mix of cargo and crew those missions might carry in the years ahead.

What this means for Boeing’s ambitions and reputation

For Boeing, the reconfigured Starliner plan is both a setback and a lifeline. The company entered the Commercial Crew Program with ambitions to be a co-equal provider of astronaut transport, leveraging its long history in aerospace to compete directly with newer players. The reality, underscored by the fumbled astronaut flight and the subsequent decision to fly cargo only in 2026, is that Boeing now has to rebuild trust with NASA and demonstrate that it can deliver consistent, trouble-free performance before it can reclaim that original vision. The temporary demotion to cargo and test roles reflects a lower level of confidence than Boeing once enjoyed, but it also preserves a path forward if the company can show that its propulsion updates, thruster redundancy changes, and other fixes translate into a smoother, more predictable spacecraft.

I read this as a reputational inflection point. If the April 2026 mission goes well, Boeing can argue that it has learned from its mistakes, stabilized the vehicle, and earned another look at crewed operations. If it stumbles again, the narrative will harden around the idea that Starliner is a troubled program that never quite lived up to its billing, especially when compared with the steady cadence of flights from competitors. In that sense, the cargo-only mission is not just about delivering supplies to orbit, it is about delivering a performance that convinces NASA, Congress, and the public that Boeing still deserves a central role in human spaceflight.

NASA’s risk calculus and the priority of redundancy

From NASA’s perspective, the recalibrated Starliner plan reflects a careful risk calculus. The agency has always emphasized redundancy in access to low Earth orbit, arguing that relying on a single provider for astronaut transport is a strategic vulnerability. Starliner was supposed to be one half of that redundancy, paired with other vehicles to ensure that a problem with any one system would not ground the entire U.S. crewed presence in orbit. By shifting the next mission to cargo only, NASA is accepting a temporary reduction in its near-term options for crew transport in exchange for a more measured, data-driven path to eventual certification.

That tradeoff is easier to make because NASA still has other ways to get astronauts to the station, but it is not cost free. Every delay in bringing Starliner up to full crewed capability extends the period in which the agency is more dependent on a narrower set of vehicles, and it complicates long-range planning for crew rotations, science schedules, and station maintenance. At the same time, NASA’s insistence on additional testing and contract modifications underscores its willingness to slow down rather than compromise on safety, a stance that aligns with its public messaging about the importance of thorough end-to-end testing and robust redundancy in critical systems.

Technical focus: propulsion, thrusters, and end-to-end validation

Technically, the April 2026 mission is being framed as an opportunity to validate Starliner’s most sensitive systems under real operational stress. The emphasis on propulsion updates and thruster redundancy is not incidental, it goes to the heart of what makes a spacecraft safe and controllable during ascent, orbital maneuvers, docking, and reentry. By flying uncrewed, engineers can push those systems through a wider range of scenarios, including contingency modes that might be too risky to attempt with astronauts on board, and they can collect detailed telemetry that would be difficult to replicate in ground tests or simulations.

End-to-end validation is particularly important for a vehicle that has already shown vulnerabilities in flight. It is one thing to test a thruster or a propulsion component in isolation, and another to see how the entire system behaves when it is integrated, fueled, and operating in the complex environment of low Earth orbit. The cargo-only mission gives NASA and Boeing a chance to observe that full stack performance from launch to landing, to verify that redundancy schemes behave as designed, and to identify any remaining edge cases that need to be addressed before people are allowed back on board. In that sense, the mission is as much a diagnostic exercise as it is a logistics run.

Implications for the International Space Station and beyond

For the International Space Station, Starliner’s new role is both a help and a reminder of lingering uncertainty. On the positive side, an additional cargo-capable vehicle adds flexibility to the station’s resupply chain, which already depends on a mix of commercial and international partners to keep its laboratories stocked and its systems maintained. The ability of Starliner-1 to deliver necessary cargo to the orbital laboratory, as spelled out in NASA’s modified contract, means that the station can benefit from another route for supplies, spare parts, and experiment hardware, even if the spacecraft is not yet ready to carry crew.

At the same time, the station’s long-term planning has to account for the fact that one of its intended crew transport vehicles is still in a probationary phase. That affects how NASA sequences crew rotations, how it allocates resources among different providers, and how it thinks about contingency scenarios in which a vehicle might be grounded unexpectedly. The April 2026 mission will therefore be watched closely not only for what it delivers to the station, but for what it reveals about Starliner’s readiness to take on a larger share of the workload in the years before the station’s eventual retirement and in any follow-on platforms that might replace it.

The road ahead to possible recertification

Looking beyond April 2026, the central question is whether Starliner can earn its way back to crewed status. NASA has been clear that certification of Boeing’s Starliner remains an objective, but it has also tied that goal to the successful execution of the upcoming cargo mission and to the broader set of technical and operational milestones that will follow. The agency’s willingness to modify its contract, redefine Starliner-1 as a cargo flight, and describe the spacecraft’s current status as a temporary demotion all point to a conditional future in which further crewed missions will depend on hard evidence that the vehicle’s problems have been resolved.

For Boeing, that means the path to recertification runs through meticulous preparation, flawless execution, and transparent reporting of the April 2026 flight’s results. Any sign of lingering issues in propulsion, thruster redundancy, or other critical systems will invite renewed scrutiny and could prompt NASA to further limit Starliner’s role or to shift more resources to alternative providers. Conversely, a clean mission that delivers cargo on time, docks and undocks smoothly, and returns safely to Earth would strengthen the case for giving Starliner another chance at carrying astronauts, even if that opportunity comes later and in a more constrained form than originally envisioned.

More from MorningOverview