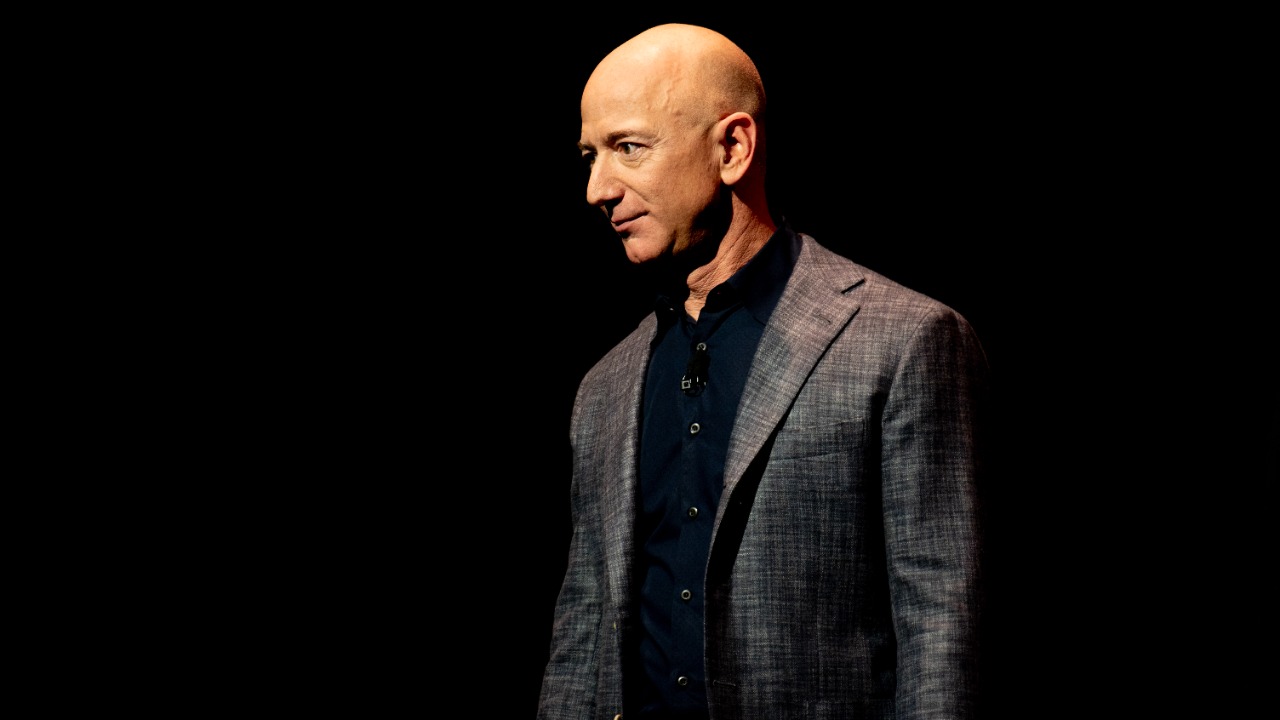

Jeff Bezos is no longer content to play the long game in cislunar space. Blue Origin is now working to put hardware on the Moon by 2026, positioning its landers and rockets as a direct counterweight to SpaceX at the very moment NASA’s Artemis schedule is wobbling and the commercial race is opening up.

I see a clear strategic pivot: instead of waiting for NASA to dictate the tempo, Bezos is using self-funded missions, a heavy-lift launcher, and a larger lunar lander to argue that Blue Origin can be the dependable alternative if SpaceX slips, and that the Moon is big enough for two dominant players.

Bezos accelerates Blue Origin’s lunar timetable

Blue Origin’s shift toward a 2026 lunar landing target is as much about narrative as it is about engineering. By pulling forward its ambitions, the company is signaling that it wants to be judged not as a perpetually future-focused lab but as a near-term transportation provider that can actually reach the Moon’s surface while NASA and its partners sort out Artemis. That acceleration reframes Jeff Bezos from patient benefactor into an operator trying to match, and eventually outpace, SpaceX’s cadence.

The centerpiece of that push is the Blue Moon Mark 1 lander, a cargo vehicle designed to touch down at the Moon’s south pole and sized to dwarf Apollo-era hardware. When Blue Origin showed off the vehicle on Nov 23, 2025, the company emphasized that the Lunar Lander Way Bigger Than Apollo would be capable of delivering substantial payloads to the south polar region, a scale that underpins any realistic plan for bases or resource extraction. That hardware, paired with a more aggressive schedule, is how Bezos is trying to turn Blue Origin from a distant promise into a near-term rival.

Mark 1 pathfinder missions as a proving ground

To make a 2026 landing credible, Blue Origin is leaning on a pair of self-funded robotic flights that function as both testbed and marketing campaign. The company has framed these early sorties as a way to validate guidance, navigation, and landing systems in the harsh lighting and terrain of the lunar poles before astronauts ever climb aboard. In practice, they are also a way to show NASA and commercial customers that Blue Origin is willing to spend its own money to retire risk.

Reporting on these plans describes how Blue Origin wants to fly two Mark 1 missions in quick succession, using the first as a Mark 1 Pathfinder to shake out systems and the second to refine operations like surface deployment and return to lunar orbit. The company has said that With the Mark Blue Origin flights, it wants to test and refine critical landing and associated systems, then demonstrate the ability to depart the surface and rendezvous in orbit. That sequence is designed to give NASA confidence that the same architecture can scale to crewed missions later in the decade.

Blue Moon Pathfinder and the Artemis V link

Those early Mark 1 sorties are not just technology demos, they are the front end of a family of landers that Blue Origin hopes will anchor NASA’s later Artemis missions. The Blue Moon Pathfinder concept is explicitly framed as a prototype, a way to fly a near-final configuration of the Blue Moon Mark 1 before it is asked to carry higher stakes cargo or crew. By treating the first mission as a prototype in flight, the company is trying to compress the usual gap between test article and operational vehicle.

According to program descriptions, the Mark 1 Pathfinder is planned as a flight test of a prototype Blue Moon Mark 1 lander that will launch no earlier than the middle of the decade, with the broader Blue Moon family expected to support NASA’s Artemis V mission in 2030. The Mark Pathfinder Blue Moon Pathfinder Blue Moon Mark lineage is central to Blue Origin’s pitch that it is not just building a one-off cargo ship but a modular system that can evolve from robotic deliveries to human-rated landers tied directly into NASA’s long-term lunar architecture.

New Glenn as the backbone of Bezos’s Moon strategy

No lunar lander flies without a heavy-lift rocket, and for Blue Origin that role belongs to New Glenn. Bezos has long argued that reusable launch is the economic foundation for any serious space economy, and New Glenn is his answer to SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy and Starship. The rocket is designed to loft large payloads to orbit and beyond, with a reusable first stage intended to drive down costs over time.

Technical overviews describe New Glenn as a vehicle that, like Blue Origin’s suborbital systems, is meant to support both commercial and government customers, including missions under the National Security Space Launch program. The rocket’s early flights are expected to serve as demonstration launches required for certification, with timelines that place operational use between early 2026 and late 2027. Those details, outlined in references to National Security Space Launch, underscore why New Glenn is so central to Blue Origin’s Moon plans: it is both the workhorse for Mark 1 missions and a revenue-generating platform in its own right.

New Glenn versus Starship in the heavy-lift market

Bezos is not shy about the competitive framing. New Glenn is being marketed as a middle path between traditional expendable rockets and SpaceX’s fully reusable Starship, a vehicle that promises enormous capacity but is still working through a long test campaign. Blue Origin is betting that some customers will trade absolute payload for schedule confidence and regulatory comfort, especially if Starship’s development continues to encounter delays.

Analysts have noted that Blue Origin is positioning itself as the reliable middle option, more capable than legacy rockets yet more available than a still-maturing super heavy system, and that the market for large payloads is big enough for two players. Commentaries on Blue Origin New Glenn emphasize that this rivalry with SpaceX is not just about prestige but about capturing a share of government and commercial contracts that will fund deeper lunar ambitions.

NASA’s shifting Artemis landscape and Blue Origin’s opening

The timing of Blue Origin’s lunar push is not accidental. NASA’s Artemis 3 mission, which is supposed to deliver the first crewed lunar landing since the Apollo era, has been under pressure as schedules slip and hardware milestones move to the right. That uncertainty creates an opening for alternative providers who can promise a credible path to the surface if the primary plan falters.

Coverage of recent program reviews notes that NASA’s Artemis 3 mission, aiming for the first crewed lunar landing since Apollo, currently lacks a firm date as the agency weighs new lunar landing profiles from both SpaceX and Blue Origin. Reports on Key Takeaways NASA Artemis Apollo describe how both companies have been asked to refine their concepts, a process that effectively elevates Blue Origin from backup to co-architect in NASA’s thinking about how to reach the Moon in the second half of the decade.

SpaceX delays reshape the competitive clock

For years, SpaceX’s Starship looked so far ahead of the field that competition felt almost theoretical. That perception is changing as the realities of integrated testing, refueling in orbit, and human-rating a brand new system collide with NASA’s timelines. Each delay in Starship’s path to operational status narrows the gap that Blue Origin needs to close.

Program updates have pointed out that SpaceX has completed 11 integrated test flights of its Super Heavy booster, demonstrating feats like catching and reusing multiple stages, but that the first crewed lunar landing using Starship is now expected no earlier than the middle of 2026. One detailed account of Blue Origin’s progress amid an Artemis 3 contract shakeup notes that Oct Lunar Looming Artemis Beyond In the context of those delays, Blue Origin’s own schedule suddenly looks less hypothetical and more like a viable alternative if NASA needs redundancy.

Leaked expectations for SpaceX’s Moon landing window

The competitive calculus sharpened further when internal expectations about SpaceX’s lunar readiness surfaced. A leaked memo suggested that the company’s first human landing on the Moon would likely slip beyond NASA’s earliest hopes, pushing the operational window into the later 2020s. For Blue Origin, that kind of delay is not just a headline, it is a strategic opportunity to argue that its more incremental approach can deliver sooner.

According to reporting on the memo, which was described by Audrey Decker at Politico, SpaceX is now expected to be ready to land humans on the Moon in September of a later year, with a broader target of June 2027 for full readiness. The account notes that Nov In the Audrey Decker Politico Moon memo, SpaceX is portrayed as likely to miss earlier deadlines, a shift that makes Blue Origin’s 2026 target more than just aspirational rhetoric.

Bezos’s political and NASA positioning

Jeff Bezos has spent years trying to align Blue Origin with NASA’s institutional needs, and that effort is now paying off in the form of major contracts and a more central role in Artemis planning. When NASA selected Blue Origin to build lunar landers for future moonwalkers, it was a clear signal that the agency wanted redundancy and competition in its human landing systems, not a single point of failure. That decision also validated Bezos’s argument that his company could deliver complex, crew-capable hardware, not just suborbital tourism.

In May 2023, NASA announced that it had picked Bezos’ Blue Origin to build lunar landers for moonwalkers, a decision highlighted in Science May coverage on May 19, 2023 at 3:42 PM EST from CAPE Canaveral, and one that followed a contested procurement where a previous award to SpaceX had been upheld. The report notes that NASA Bezos Blue Origin Science May EST CAPE secured a contract that some critics pegged at 42 as a shorthand for its scale and significance, underscoring how deeply intertwined Blue Origin now is with the agency’s long-term lunar plans.

New Glenn’s sudden rise and the broader rivalry

As New Glenn edges closer to operational status, its role in the broader rivalry with SpaceX is becoming more visible. The rocket is no longer a paper design but a vehicle that NASA and commercial customers are starting to factor into their launch manifests. That shift changes how policymakers and investors view Blue Origin, recasting it from a distant challenger into an active competitor in the heavy-lift market.

Commentary on the rocket’s emergence notes that, according to Ars Technica and other observers, Blue Origin’s New Glenn has suddenly become a competitor that NASA is willing to trust with science missions, including probes that will investigate how the solar wind interacts with planetary environments. One analysis framed this as a turning point in the Nov Opinion Blue Origin New Glenn NASA rivalry with SpaceX, arguing that once New Glenn proves itself on government payloads, its role in supporting lunar missions will be far harder to dismiss.

NASA reopens the door on lunar lander options

NASA’s own procurement strategy is also tilting the field in Blue Origin’s favor. After initially awarding the first human landing system to SpaceX, the agency has moved to broaden its options, inviting additional providers to propose landers for later Artemis missions. That shift reflects both political pressure for competition and a sober assessment of the risks of relying on a single, unproven architecture.

Coverage of NASA’s evolving approach notes that Jeff Bezos’ Blue Origin, along with other companies, has been encouraged to compete for new Moon landing opportunities as the agency reassesses its plans for Starship. Reports from Florida highlight that Oct Jeff Bezos Blue Origin and others could offer additional lunar lander options to NASA, a process that effectively institutionalizes the competition between Blue Origin and SpaceX rather than treating it as a one-off contest.

Technical contrasts in the two lunar architectures

Underneath the politics and contracts, the technical differences between Blue Origin’s and SpaceX’s lunar plans are stark. SpaceX is pursuing a fully reusable, single-stack architecture that relies on multiple refueling flights in Earth orbit before a Starship variant heads to the Moon. Blue Origin, by contrast, is building a more traditional stack of a heavy-lift rocket and a dedicated lander, with a focus on incremental testing and modular upgrades.

Analyses of the two approaches point out that SpaceX has demonstrated a few critical capabilities, such as the catch and reuse of multiple Super Heavy boosters, but still faces an unknown number of tanker missions and complex in-space refueling before its lunar variant can fly. Blue Origin, meanwhile, has only just begun to fly its large orbital hardware, but its architecture avoids some of the most novel elements of Starship’s design. A detailed comparison in late October framed these differences in the context of Oct Super Heavy But, suggesting that Blue Origin’s more conservative design could prove advantageous if regulators or NASA grow wary of Starship’s complexity.

Bezos’s public case for Moon bases

Jeff Bezos has always framed his lunar ambitions in grand terms, talking about millions of people living and working in space and using the Moon as a stepping stone for deeper exploration. Recently, he and his leadership team have sharpened that message, arguing that permanent infrastructure on the Moon is not a sci-fi dream but a near-term industrial project that requires reliable transportation and heavy cargo capacity. That rhetoric is aimed at both policymakers and potential partners who might help fund or operate lunar bases.

In a public discussion posted on Nov 22, 2025, Blue Origin’s chief executive described Bezos as both tactically impatient and strategically patient, highlighting how he pushes for near-term milestones like the first Mark 1 landing while keeping his eye on long-term goals like lunar bases and in situ resource utilization. The conversation, captured in a video where speakers repeatedly reference Nov as a marker of the current phase of the program, is available on Nov and offers a rare glimpse into how the company’s leadership sees the balance between bold vision and incremental progress.

Public sparring and the optics of rivalry

The rivalry between Bezos and Elon Musk is not confined to engineering reviews and contract awards, it also plays out in public jabs and carefully crafted infographics. Blue Origin has at times taken direct aim at SpaceX’s technical choices, arguing that certain architectures are too risky or too complex for NASA’s timelines. Those critiques are as much about shaping perception in Washington as they are about genuine technical disagreement.

One notable example came on May 30, 2025, when observers spotted a new Blue Origin infographic on a Wednesday that dissected SpaceX’s plan to refuel Starship in orbit, a graphic that was quickly picked up in a CNBC report. The company used the visual to argue that its own approach to reaching the Moon was more straightforward, a point underscored in coverage that described how Wednesday CNBC framed the move as a huge swing at SpaceX. That kind of public sparring reinforces the sense that the 2026 Moon landing race is as much about narrative dominance as it is about who plants the next flag.

More from MorningOverview