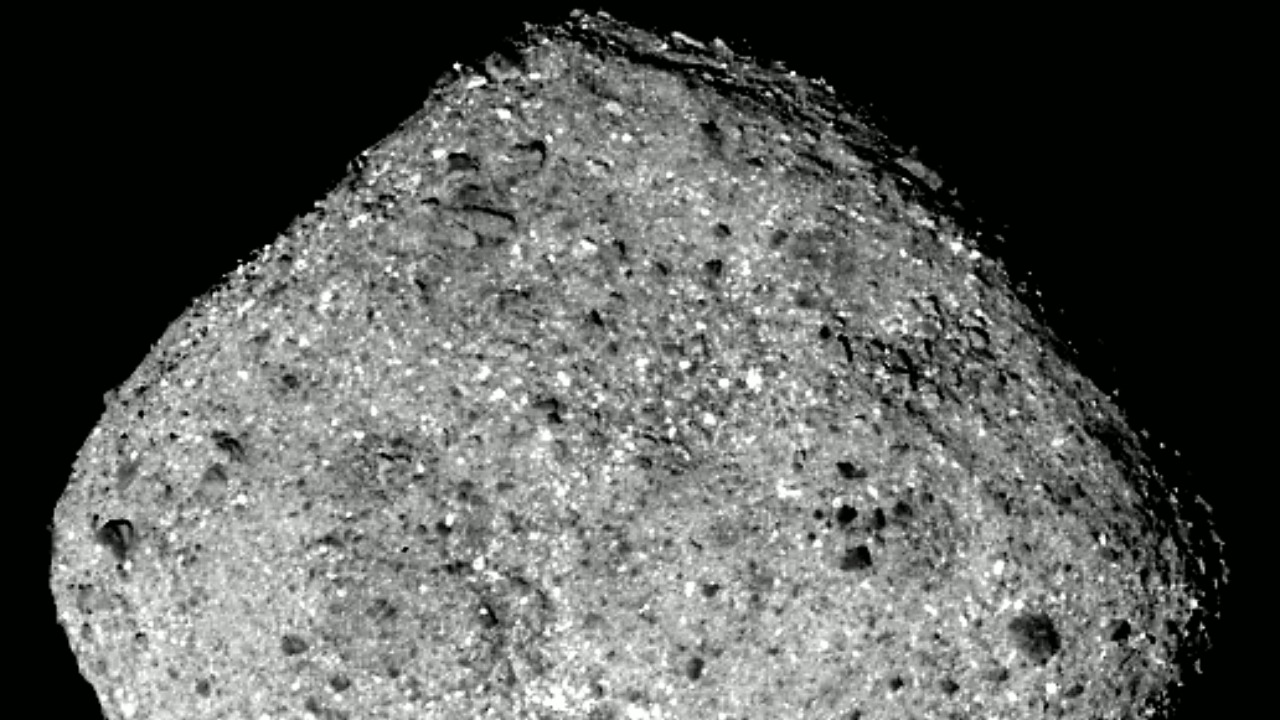

When scientists cracked open the first grains from asteroid Bennu, they expected a time capsule of rock and dust. What they found instead was a cocktail of sugars, phosphates, evaporite salts, and a strange, sticky “space gum” that looks nothing like the tidy textbook picture of a primitive asteroid. The samples are forcing researchers to redraw the early solar system, and they hint that the ingredients for biology were mixed in more exotic ways than anyone had predicted.

The new material from Bennu is not just chemically rich, it is structurally odd, with ultra‑pure crystals, delicate coatings thinner than a human hair, and fragile clumps that barely survived the trip home. Taken together, these discoveries suggest Bennu’s parent body was once a warm, salty world, and that its rubble preserves some of the most pristine “original ingredients” for life that scientists have ever held in a lab.

The mission that brought Bennu home

The story starts with the Origins, Spectral Interpretation, Resource Identification, and Security – Regolith Explorer, better known as OSIRIS-REx, which was launched to rendezvous with Bennu and return a sample of its surface. The spacecraft’s sampler head briefly touched the asteroid, stirred up a cloud of loose material, then sealed away a cache of dark grains that would later be delivered to Earth. That maneuver turned Bennu from a distant point of light into a physical archive of the early Solar System that researchers could weigh, heat, dissolve, and probe grain by grain.

Those grains are now at the center of a coordinated campaign across laboratories in the United States and abroad, with teams dissecting everything from their mineral structure to their organic chemistry. The mission’s curators describe Bennu as holding the Solar System’s “original ingredients,” and early analyses suggest the asteroid may once have been part of a larger, wetter world that was broken apart and scattered. That idea is grounded in a deep dive into the returned material, which shows that Bennu preserves minerals and textures that simply do not form on a cold, inert rock.

A sticky surprise: the “space gum” coating

Among the most visually striking finds is a thin, sticky coating that clings to some of the grains, a material researchers have nicknamed “space gum.” Under the microscope, this substance appears as a translucent film that binds particles together, giving parts of the sample a clumped, almost chewed texture that no one expected from an airless asteroid. Analyses show that this gum-like material is rich in complex organic molecules, suggesting that Bennu’s surface chemistry is far more intricate than a simple mix of rock and ice.

What makes the “space gum” so intriguing is its structure: in some places it forms layers thinner than a human hair, wrapping individual grains in a protective skin. That delicate architecture hints at slow, cumulative processes on Bennu’s surface, where organic-rich films may have built up over time as the asteroid was bombarded by radiation and micrometeorites. The presence of this coating was highlighted when scientists reported that Asteroid Bennu Samples Carry Mysterious Space Gum, Sugars, Ton of Stardust, Learn, underscoring how alien this material is compared with the more familiar meteorites that fall to Earth.

Sugars in stone: ribose, glucose, and the “gum” connection

Alongside the sticky coating, Bennu’s grains contain something even more consequential for origin-of-life research: bio-essential sugars. A team of Japanese and US scientists has identified ribose and glucose in the samples, molecules that are central to RNA and energy metabolism in modern biology. Finding these sugars locked inside an asteroid fragment shows that such compounds can form and survive in space, long before any planet develops oceans or atmospheres.

Researchers think the presence of these sugars is linked to the same processes that produced the gum-like organics, with water-rich reactions and radiation chemistry working together on Bennu’s parent body. The discovery was detailed in a Dec News and Events item under News Releases and Multimedia from NASA, which reported that Sugars, ‘Gum,’ Stardust Found in NASA samples, and that the same grains hosting the sticky material also carry these fragile carbohydrates. That pairing strengthens the idea that Bennu’s organics are not random contamination but part of a coherent chemical environment that once existed on a much larger body.

Ultra-pure phosphates and a clue to hidden oceans

If the organics tell one part of Bennu’s story, the phosphates tell another. In one of the most surprising mineral finds, scientists identified a magnesium-sodium phosphate crystal that stands out for its extraordinary purity, with almost no other elements mixed in. On Earth, phosphates are often tangled up with a host of other minerals, so encountering such a clean crystal in an asteroid sample suggests it formed in a very specific, controlled environment.

That environment likely involved liquid water and slow evaporation, conditions more reminiscent of a briny pond than a dry rock in space. The magnesium-sodium phosphate was first flagged in a detailed analysis of the Bennu grains, which noted that the Surprising Phosphate Finding in the NASA OSIRIS Asteroid Sample from Bennu could only be explained if the parent body once hosted pockets of water that slowly concentrated dissolved salts. A separate discussion of the same crystal emphasized that the magnesium-sodium phosphate found in the Bennu sample stands out for its purity, and that this unusual composition was highlighted by researchers including Dante Lauretta, as reported in Jun Bennu coverage.

A long-lost salty world behind a rubble pile

Put together, the phosphates, organics, and salts point back to a parent body that was far more complex than the small rubble pile we see today. Evidence of evaporite minerals, which form when salty water dries up, indicates that the interior of Bennu’s ancestor was warm enough to support liquid water for a substantial period. That warmth would have allowed dissolved chemicals to circulate, react, and eventually crystallize into the pure phosphates and other salts now seen in the sample.

In one analysis, scientists argued that finding evaporites means Bennu comes from a long-lost salty world, a larger object that may have had internal heating and a layered structure before it was shattered. They also reported that fourteen of the 20 amino acids essential for life on Earth have been detected in related asteroid material, reinforcing the idea that such bodies can stockpile the raw materials for biomolecules like DNA and RNA. These conclusions were drawn from work showing that Jan Finding Bennu connects the asteroid to a once-wet world that has long since disappeared, leaving only fragments like Bennu as witnesses.

Stardust, magnetite, and the deep-time archive

Beyond the chemistry of water and organics, Bennu’s grains carry physical traces of events that predate the Solar System itself. Embedded in the dark matrix are tiny specks of stardust, grains forged in dying stars and later swept into the cloud that formed the Sun and planets. Analyses of the returned material show a higher concentration of these presolar grains than many researchers expected, suggesting that Bennu managed to preserve a particularly pristine slice of that ancient mixture.

Those stardust grains sit alongside microscopic crystals of magnetite, an iron oxide mineral that forms in the presence of water and can record magnetic fields. The Bennu samples revealed magnetite crystals less than 1 micrometer in size, with individual crystals identified as potential recorders of the conditions in the early Solar System. Reports on the sample return noted that Jan The Bennu grains contain both these magnetite particles and a suite of organic compounds, tying together the physical and chemical records of the Solar System’s first days.

Life’s “building blocks” and the sugar–phosphate link

For origin-of-life researchers, the most tantalizing aspect of Bennu is how many different “building blocks” show up in the same handful of dust. Scientists have detected amino acids, sugars, and phosphates, the same categories of molecules that underpin proteins, nucleic acids, and cellular energy systems on Earth. The coexistence of ribose, glucose, and magnesium-sodium phosphate in a single sample suggests that the basic components of RNA-like chemistry can assemble in space without any help from biology.

One research team framed the OSIRIS-REx haul as a direct test of the idea that asteroids delivered key ingredients to the early Earth before life began. They pointed out that the OSIRIS-REx mission successfully returned samples from Bennu, and that these grains contain a mix of organics and minerals that could have seeded prebiotic chemistry on the young planet. Coverage of this work emphasized that Scientists Bennu The OSIRIS findings strengthen the case that at least some of life’s raw materials were imported from space rather than synthesized entirely on Earth’s surface.

Comparing Bennu to other cosmic time capsules

Bennu is not the first asteroid to deliver a sample to Earth, but it is quickly becoming one of the most chemically revealing. Earlier missions returned smaller amounts of material that already hinted at organic chemistry in space, yet Bennu’s combination of sugars, phosphates, and evaporites appears unusually rich. That richness may reflect the specific history of its parent body, which seems to have experienced both deep freezing and episodes of internal heating that allowed water to flow and react with rock.

Researchers studying how organics emerged in the deep freeze of the early Solar System have long noted that one of the main challenges in understanding that era is finding any pristine material from the period to analyze. Most meteorites that fall to Earth have been altered by atmospheric entry, weathering, or terrestrial contamination, which obscures their original chemistry. A detailed discussion of this problem stressed that One of the key advantages of missions like OSIRIS-REx is that they deliver untouched material, allowing scientists to compare Bennu’s pristine organics with those in more weathered meteorites and build a clearer picture of how chemistry evolved across different environments.

From lab benches to cosmic context

Inside the laboratories now handling Bennu’s grains, the work is painstaking and methodical, but the implications reach far beyond the sample trays. Teams are using high resolution instruments to map where each sugar, salt, and mineral sits within the rock, building three dimensional reconstructions of the asteroid’s microstructure. Those maps reveal, for example, that the gum-like organics often coat or infiltrate cracks in the rock, while the pure phosphates occupy distinct pockets that likely formed as brines cooled and crystallized.

At the same time, astronomers are using telescopes to search for other asteroids that might share Bennu’s spectral fingerprints, hoping to identify siblings from the same long-lost parent body. Observations have already imaged 42 of the biggest asteroids in our Solar System, and instruments like Webb have detected a previously unknown 100–200-mete scale object in the outer regions, expanding the catalog of potential targets. These broader surveys were highlighted in work noting that Jan Astronomers Solar System Webb are now linking the detailed chemistry of Bennu to the wider population of small bodies, turning a single sample return into a reference point for the entire asteroid belt.

Why Bennu’s oddities matter for life’s origins

All of these strands, from the sticky gum to the ultra-pure phosphates, converge on a simple but profound question: how did lifeless chemistry on small bodies like Bennu set the stage for biology on planets like Earth? The Bennu samples show that even a modest rubble pile can host a surprising diversity of molecules and minerals, assembled under conditions that include liquid water, radiation, and long periods of slow cooling. That environment is capable of producing sugars, amino acids, salts, and stardust in close proximity, a combination that many origin-of-life models consider fertile ground for complex reactions.

When NASA brought home pieces of the asteroid, researchers expected to refine their models of early Solar System chemistry; instead, Bennu has forced them to widen those models to include exotic materials and processes that had not been fully appreciated. Analyses of the grains indicate that Dec Stardust and Asteroid Bennu When NASA uncovered more stardust from dying stars than anyone expected, along with a richer suite of organics and salts. In that sense, the “strange new material” from Bennu is not just a curiosity, it is a reminder that the path from dust to life may have run through worlds and chemistries that we are only now beginning to recognize.

The next questions Bennu will have to answer

Even with this flood of data, Bennu’s samples are still in their scientific infancy, and many of the most pressing questions remain open. Researchers are now trying to determine how the different components of the gum-like organics, sugars, and phosphates interact when heated, irradiated, or dissolved, experiments that could mimic conditions on the early Earth or on other young planets. They are also probing whether the chirality, or “handedness,” of Bennu’s organic molecules shows any bias, a subtle property that might hint at why life on Earth favors one orientation over another.

As those experiments proceed, the OSIRIS-REx sample curation teams are carefully preserving a large fraction of the material for future generations, betting that new instruments and theories will extract even more information from the same grains. Additional context about the mission’s journey and the scientific community’s response has been provided in reports noting that Jun NASA OSIRIS Origins Spectral Interpretation Resource Identification returned a sample that is already reshaping planetary science. If Bennu’s first surprises are any guide, the most transformative insights may still be hiding in grains that have yet to be opened.

A new baseline for “primitive” worlds

For decades, planetary scientists used the term “primitive” to describe asteroids and comets that had not melted or differentiated like planets, assuming their interiors were simple mixtures of rock and ice. Bennu’s samples challenge that picture by revealing a rubble pile built from fragments of a once active, salty world, where water circulated, minerals crystallized, and complex organics accumulated over time. In that sense, Bennu is primitive only in the chronological sense, not in its chemical or structural sophistication.

As I look across the emerging results, I see Bennu setting a new baseline for what we expect from small bodies in the Solar System. Instead of inert leftovers, they now appear as dynamic laboratories where the ingredients for life can be concentrated, transformed, and preserved for billions of years. The strange new material no one expected, from the space gum to the pure phosphates, is not an anomaly to be explained away, but a signal that our inventory of cosmic environments capable of nurturing prebiotic chemistry has been far too narrow.

More from MorningOverview