Human brains evolved under the steady pull of gravity, yet modern astronauts are spending months at a time in orbit, where that basic force is stripped away. A growing body of research now shows that the brain does not simply adapt in subtle ways, it physically reshapes, with fluid-filled spaces expanding, neural wiring reorganizing, and some changes persisting for years after landing. Those findings are forcing space agencies to rethink what long missions to the Moon and Mars will demand of the human body and mind.

Instead of a temporary wobble, scientists are documenting structural shifts that scale with how long someone lives off Earth, and in some cases with how often they go back. The picture that emerges is of a remarkably plastic organ that can warp and reconfigure to keep astronauts functioning in orbit, but that may also carry long term trade offs that mission planners can no longer afford to treat as an afterthought.

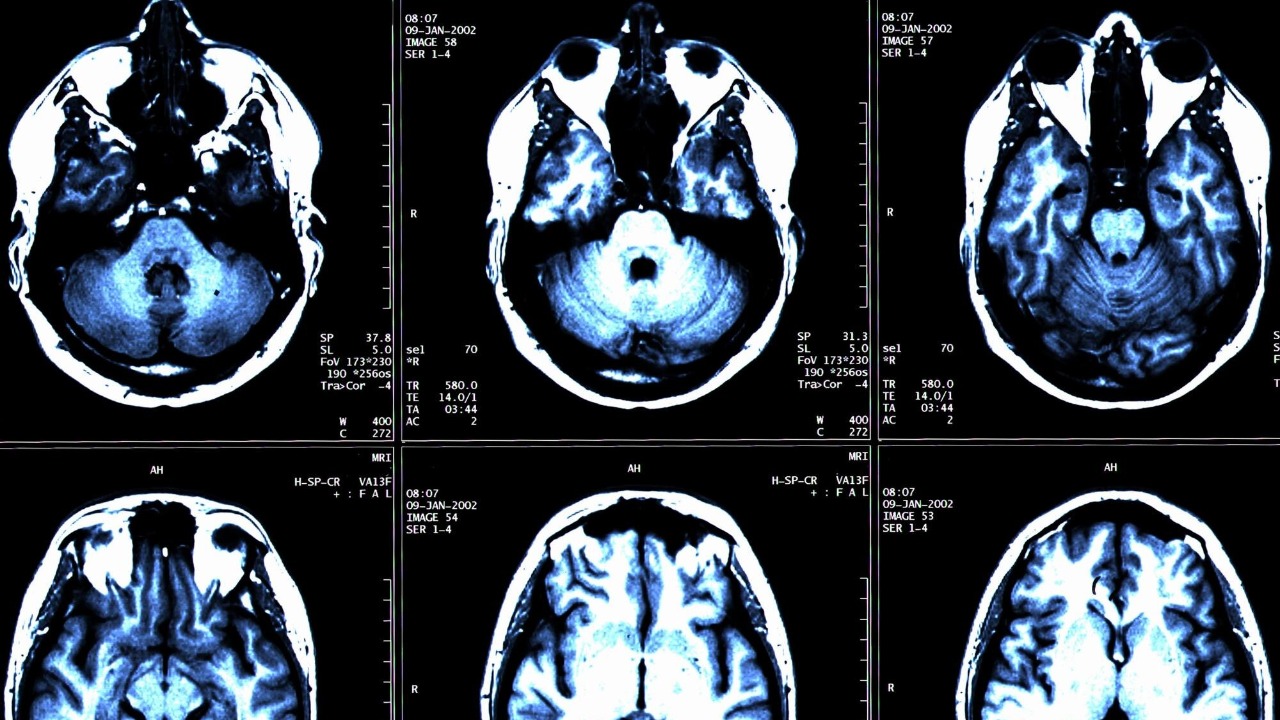

What scientists are actually seeing inside astronauts’ heads

When researchers first began comparing brain scans before and after missions, they were struck by how global the reshaping looked. In one early analysis of 26 astronauts, the brains of all 26 changed configuration after their time away from Earth, with the degree of distortion greater in those who had spent longer in orbit, a pattern that pointed to microgravity as the driver rather than random variation, and that was detailed in structural scans. Follow up work using more refined imaging has focused on the brain’s ventricles, the fluid filled cavities that cushion and nourish neural tissue, and has found that these spaces can enlarge markedly after long missions, a sign that cerebrospinal fluid is being redistributed in the skull. In a study that examined regional gray matter volume and white matter microstructure, scientists led by Jun and colleagues reported that longer missions were associated with greater post flight ventricular expansion, reinforcing the idea that time in orbit is directly linked to the scale of these internal shifts, as described in detailed voxelwise analyses.

Those ventricles are not empty voids, they are filled with cerebrospinal fluid that normally circulates under the influence of gravity, and in microgravity that circulation is altered. Imaging work that grouped eight astronauts who flew roughly two week missions, 18 who spent about six months in orbit, and four who stayed for approximately one year found that the longest serving group had the most pronounced ventricular enlargement, and that the medium duration group sat in between, a dose response pattern that was highlighted in coverage of how long term travel affects the brain. A related analysis of 30 astronauts, which again split them into eight two week flyers, 18 six month residents, and four who logged about a year, concluded that mechanisms in the human body that normally manage fluid distribution are disrupted in orbit, causing the ventricles to expand and stay enlarged for months after landing, according to Of the 30 cases examined.

From warped ventricles to rewired networks

Ventricular expansion is only part of the story, because the brain’s wiring also appears to reorganize in response to life in orbit. When neurologists analyzed functional connectivity in cosmonauts before and after long missions, they saw key changes in neural connections between several motor areas and altered communication in regions that integrate sensory information, a pattern that suggested the brain was reweighting inputs to cope with a world where “up” and “down” no longer exist, as described when investigators reported what they saw When analyzing the images. A separate study of cosmonauts found that long missions appeared to “rewire” white matter tracts, with Our brains changing not only as we age and grow here on Earth but also in distinctive ways after extended spaceflight, a contrast that was underscored when scientists asked what happens to the human brain after being in orbit for a long time and reported that Our and Earth based patterns diverged, as noted in work that emphasized how Our brains adapt.

Structural imaging backs up those functional findings. In a retrospective analysis of T2 weighted MRI scans from 27 astronauts, including thirteen roughly two week shuttle crew members and 14 who had flown longer station missions, researchers documented shifts in gray matter distribution and deformation of tissue near the top of the brain, changes that correlated with balance data and hinted at underlying mechanisms and behavioral consequences, as described in a study that relied on MRI scans. Earlier work using sensor based balance tests and imaging had already shown that regions involved in leg movement and processing sensory information from the lower body expanded in volume after spaceflight, suggesting that the brain was reallocating resources to help astronauts navigate in three dimensions, a pattern that was highlighted when researchers described how those sensor driven measures lined up with structural changes.

How long the changes last, and why mission length matters

One of the most unsettling findings is that some of these alterations do not snap back quickly. Work that tracked astronauts for years after six month missions found that ventricular enlargement and certain connectivity changes persisted well beyond the initial recovery period, suggesting that the brain settles into a new equilibrium rather than fully reverting to its preflight state, a pattern that was emphasized in reporting that six months in orbit can change your brain for years and that featured NASA astronaut and Expedition 66 Flight Engineer Mark Vande Hei peering through the International Space Station’s window, as described in a piece on how Six Months in orbit affects neural tissue. A separate analysis of perivascular spaces, the channels where cerebrospinal fluid flows alongside blood vessels, found that new astronauts showed measurable changes in these PVS structures after their first long mission, while more experienced flyers had less additional alteration, hinting at a ceiling effect where the brain may only be able to remodel so much, a pattern that was documented when Researchers examined PVS before and after flight.

Mission duration also appears to shape how reversible the changes are. In the work led by Jun and colleagues, Here the team found that longer missions were tied not only to greater ventricular expansion but also to slower recovery, with some astronauts still showing enlarged fluid spaces long after landing, as detailed in the Here analysis. A broader review of spaceflight effects on the brain concluded that microgravity results in headward fluid shifts that can contribute to spaceflight associated neuro ocular syndrome, a cluster of eye and vision problems that may be linked to the same pressure changes reshaping the brain, and that the number of long duration human spaceflights has increased substantially over the past 15 years, raising the stakes for understanding these mechanisms, as summarized in an Aug review.

From lab findings to real world risks for crews

Structural change does not automatically mean impairment, but there are reasons for caution. By studying brain scans of astronauts before and after missions, researchers have warned that shifts in fluid and tissue could potentially lead to cognitive impairments if they affect regions involved in attention, memory, or executive function, a concern raised in discussions of how Spaceflight might alter both structure and function. According to Roberts, basic MR imaging scans are already part of the medical operations protocol for NASA astronauts, but there had been no long term imaging follow up until these recent studies, and the new data are now being used to refine how NASA screens and supports crews, a shift described when investigators noted that, According to Roberts, the agency needed this information to move forward.

Other work has tied brain reshaping to more visible symptoms. A study led by radiologist Larry Kramer at the University of Texas found that long missions were associated with upward brain shifts, crowding at the top of the skull, and increased volume around the optic nerve and spinal cord, findings that support the theory that microgravity increases pressure in the head and may contribute to vision changes that some astronauts experience, as detailed in research on how Larry Kramer and colleagues examined these effects. A separate news feature framed these findings within a broader look at how space travel can seriously change your brain and linked them to other physiological oddities cataloged under Related sections such as The Human Body in Space: 6 Weird Facts, underscoring that the brain is part of a whole body response to microgravity that includes fluid shifts, bone loss, and cardiovascular adaptation, as described in coverage that highlighted The Human Body in Space and other Weird Facts.

Preparing brains for the Moon, Mars, and beyond

As space agencies and private companies plan missions that will keep crews away from Earth for years, the question is shifting from whether the brain changes to how to manage those changes. Human physiology is based on the fact that life evolved over millions of years while tethered to Earth gravity, and researchers studying Brains in orbit have argued that countermeasures will need to address not just muscles and bones but also the central nervous system, a point made in work that framed Brains and Human adaptation in the context of Brains in space. Some scientists have suggested that artificial gravity, refined exercise protocols, or pharmacological tools might help stabilize fluid distribution and protect sensitive structures, but those ideas remain largely experimental, and the existing data underline how much is still unknown about long term neural health in deep space.

The stakes are not only medical but operational. A video segment that asked whether spending time in orbit may change astronauts’ brains forever highlighted concerns about long term side effects and raised questions about how cognitive performance might evolve over multi year missions, as discussed in a broadcast that examined what space may do to neural tissue. Another program, the Weon podcast, has explored how lasting changes in astronauts’ brains intersect with mission design, training, and even crew selection, emphasizing that welcome to the Weon conversation is now as much about neuroscience as it is about rockets, a shift captured when the show unpacked Weon perspectives on these findings. As I weigh the accumulating evidence, I see a clear message for planners of lunar bases and Mars expeditions: the brain is not a passive passenger on these journeys, it is an active, reshaping organ whose limits and resilience will help define how far from Earth humans can safely roam.

More from Morning Overview