A small stone tablet pulled from the soil of western Georgia has opened a vast new mystery. Inscribed with dozens of unfamiliar symbols, the artifact appears to preserve a script that does not match any known ancient writing system, hinting at a lost language that once echoed through the Caucasus.

Archaeologists now face a rare and delicate challenge: to document, date, and decode a writing tradition that surfaces in the record fully formed, yet without a clear link to the scripts around it. The tablet’s 39 distinct signs, carved with deliberate care, suggest a community that not only spoke but also wrote a language that has so far escaped historical memory.

Unearthing a tablet that should not exist

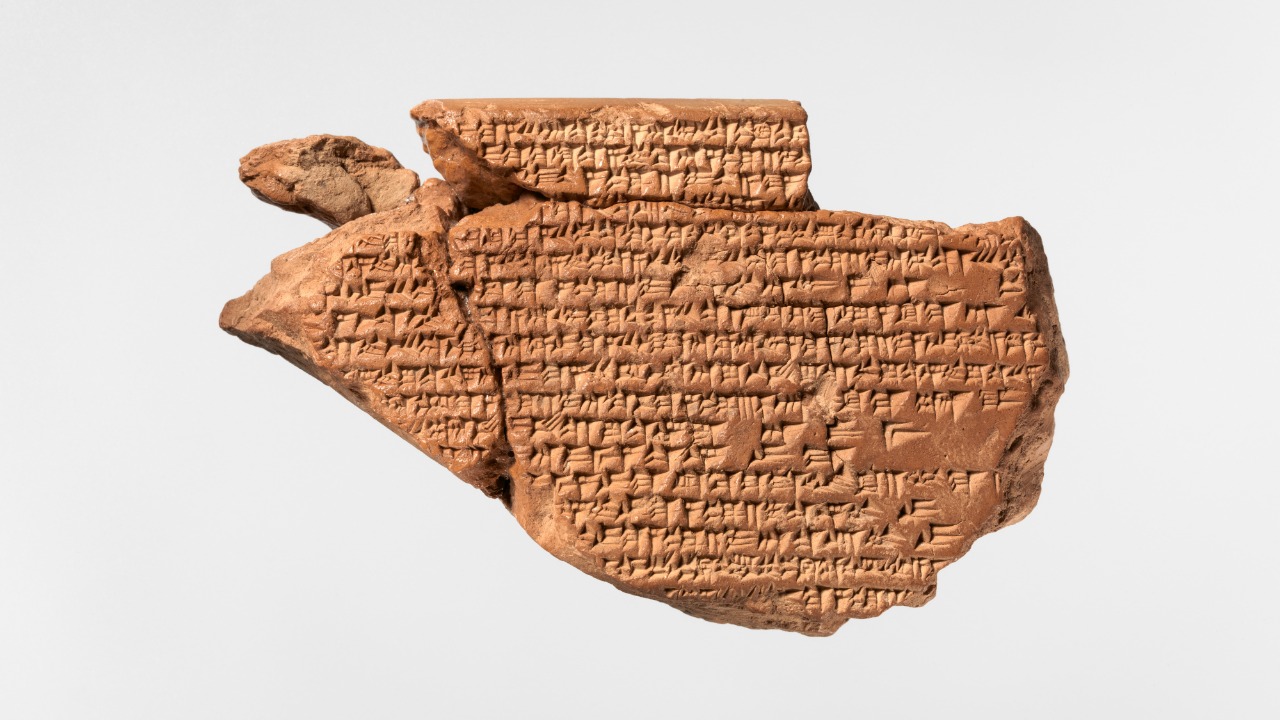

The tablet emerged from an archaeological site in western Georgia, in a region already known for Bronze and early Iron Age settlements, but not for a fully fledged writing system of its own. Excavators uncovered a compact stone slab, roughly hand-sized, bearing multiple lines of carefully incised characters that immediately stood apart from the Greek, Aramaic, or Urartian scripts typically associated with the wider region. Reporting on the find describes a total of about 60 characters on the surface, with 39 of them appearing to be unique signs that do not correspond to any cataloged alphabet or syllabary in the ancient Near East or Caucasus.

Researchers who examined high resolution images of the artifact noted that the characters are arranged in what looks like deliberate rows, with consistent spacing and repeated shapes that strongly indicate a structured script rather than random markings or decorative motifs. Coverage of the discovery highlights that the tablet was found in Georgia and that the unknown script is represented by dozens of distinct symbols, with one account emphasizing that the stone is inscribed with around 60 characters from an unknown language. Another detailed report underscores that archaeologists have identified 39 separate signs on the tablet, a figure that has quickly become central to discussions of how complex this writing system might be and whether it represents an alphabet, a syllabary, or something more intricate.

What 39 unfamiliar signs reveal about a lost script

From a linguistic perspective, the count of 39 distinct characters is striking. Many alphabetic systems operate with fewer symbols, while syllabaries and logosyllabic scripts often require larger inventories. The tablet’s sign list sits in a gray zone that could indicate an alphabet with additional diacritics, a syllabary with a limited set of syllables, or a mixed system that uses both phonetic and logographic signs. Archaeologists and epigraphers quoted in coverage of the find stress that the script does not match known Caucasian, Anatolian, or Mesopotamian systems, which suggests that the community that produced it developed its own graphic tradition rather than borrowing wholesale from neighbors.

Several analyses point out that the characters show repeated patterns and consistent line orientation, which implies that the writer was following established conventions rather than improvising. One report notes that the tablet preserves 39 different signs, while another describes about 60 total characters on the surface, a distinction that likely reflects the difference between unique symbols and their repeated use in the text. In one synthesis of the research, specialists emphasize that the script appears to be entirely new to scholarship, with no direct parallels in existing corpora of Caucasian inscriptions, a conclusion echoed in coverage that frames the find as a previously unknown language preserved on stone. That combination of internal structure and external isolation is precisely what makes the tablet so tantalizing for linguists.

Placing the mystery tablet in Georgia’s deep past

Context is everything in archaeology, and the Georgian tablet’s surroundings are as important as the symbols carved into it. Reports describe the artifact as roughly 3,000 years old, placing it in the early Iron Age, a period when the Caucasus sat at the crossroads of powerful states in Anatolia, Mesopotamia, and the eastern Mediterranean. At that time, scripts such as cuneiform, Phoenician, and various local alphabets were already in use across a wide area, yet the Georgian tablet’s characters do not align with any of those well documented systems. That chronological setting suggests that the community behind the tablet was participating in broader networks of trade and cultural exchange while still maintaining a distinct linguistic identity.

Accounts of the excavation note that the tablet was found in western Georgia, a region that has yielded evidence of complex societies with metalworking, fortified settlements, and long distance contacts. One detailed overview of the discovery explains that the stone was uncovered at a site associated with early state formation in the Caucasus, where archaeologists have also found ceramics, tools, and other material culture that point to sustained occupation. Another report, focusing on the broader implications, underscores that the tablet’s age and location place it among the earliest known examples of writing in the area, potentially predating or standing apart from later Georgian scripts. That framing, echoed in coverage that highlights the tablet as a 3,000 year old artifact from Georgia, reinforces the idea that the region’s linguistic history is more layered than previously assumed.

How archaeologists know the script is truly unknown

Declaring a script “unknown” is not something specialists do lightly. Before making that claim, epigraphers compare new inscriptions against extensive catalogs of ancient writing, from cuneiform sign lists to alphabets used across the Mediterranean and Near East. In the case of the Georgian tablet, researchers have systematically checked the 39 distinct signs against established corpora and found no convincing matches. Reports on the discovery emphasize that the characters do not correspond to Greek, Aramaic, Urartian, or any of the better documented Caucasian scripts, and that their shapes and combinations resist easy classification within existing typologies.

Several accounts describe how the team documented each sign, noting its strokes, orientation, and frequency, then compared those data to known systems. One detailed analysis explains that the script’s internal consistency, including repeated sequences of characters, strongly suggests a genuine writing system rather than random marks or pseudo script. Another report, summarizing expert reactions, notes that linguists have so far been unable to link the signs to any recognized language family, which is why the tablet is being treated as evidence of a previously unattested tongue. That cautious but firm conclusion is reflected in coverage that presents the artifact as a stone tablet inscribed with a mystery language, a phrase that captures both the excitement and the methodological rigor behind the claim.

Why decoding the tablet will be so difficult

Even when a script is clearly structured, decipherment is notoriously hard without a bilingual key or a large body of texts. The Georgian tablet, at least for now, is a single inscription with a limited number of characters, which sharply constrains what linguists can infer. Specialists quoted in coverage of the find point out that without parallel texts, proper names, or clear context such as a funerary formula, it is extremely challenging to assign sounds or meanings to the signs. The 39 distinct characters provide a tantalizing alphabet of shapes, but not yet a dictionary of words.

Reports on the discovery note that researchers are using high resolution imaging and 3D modeling to capture every detail of the inscription, in the hope that subtle features like stroke order or depth might reveal patterns. Some analyses suggest that statistical methods, including frequency analysis and comparisons with known language families in the Caucasus, could eventually narrow down possibilities. However, experts also caution that the script might represent a language with no close surviving relatives, which would make phonetic reconstruction even more complex. One overview of the challenges emphasizes that, in the absence of a Rosetta Stone style bilingual, progress will likely be incremental, a point echoed in coverage that frames the inscription as a mystery language whose secrets will not yield quickly. That sober assessment tempers public enthusiasm with a realistic sense of how long such work can take.

Rewriting the story of writing in the Caucasus

The implications of the Georgian tablet extend far beyond a single artifact. If the script represents a local writing tradition, it suggests that communities in the Caucasus were experimenting with literacy in ways that have not been captured in surviving texts. Several reports argue that the find could force scholars to rethink how and when writing spread through the region, challenging older models that cast the Caucasus primarily as a recipient of scripts from neighboring powers. Instead, the tablet hints at a more dynamic picture in which local groups adapted or invented systems to record their own languages and administrative needs.

Coverage of the discovery often situates it alongside other early writing traditions, noting that the presence of a structured script in Georgia around 3,000 years ago complicates linear narratives that move from Mesopotamia to the Mediterranean and then outward. One analysis stresses that the tablet may represent only a fragment of a much larger corpus that has yet to be found, raising the possibility that future excavations could uncover additional inscriptions in the same script. Another report, focusing on the broader stakes, frames the find as evidence that the linguistic landscape of the ancient Caucasus was more diverse than previously documented, with languages that left no direct descendants in the modern record. That perspective is reflected in accounts that describe the tablet as an ancient stone from Georgia etched with a mysterious language, a phrase that captures both the local specificity and the global significance of the discovery.

Public fascination and the long work ahead

News of the tablet has quickly spilled beyond academic circles, drawing intense interest from history enthusiasts, linguistics fans, and casual readers alike. Online discussions have dissected photographs of the inscription, with users speculating about everything from possible phonetic values to imagined links with modern languages. One widely shared thread on a dedicated archaeology forum highlights the tablet as a 3,000 year old tablet from Georgia that preserves an unknown script, and the comments reflect both genuine curiosity and a recognition that definitive answers will take time. That grassroots engagement mirrors the way other high profile decipherment puzzles, from Linear A to the Indus script, have captured the public imagination.

Specialists, for their part, are moving methodically. Video explainers featuring archaeologists and linguists have begun to walk viewers through the basics of the find, outlining what is known and what remains speculative. In one such presentation, a researcher uses close up footage of the stone to show how the characters are carved and to explain why their shapes do not match familiar alphabets, underscoring the care needed before drawing conclusions. That kind of outreach, exemplified by a detailed video overview of the tablet, helps set expectations: the inscription is a remarkable clue, not a solved puzzle. As more data emerge, including potential new finds from the same site, the conversation will likely shift from initial astonishment to the slow, collaborative work of building a corpus and testing hypotheses.

Why this one tablet matters beyond archaeology

For linguists and historians of writing, the Georgian tablet is a reminder that the global record of scripts is still incomplete. Each newly identified system forces scholars to revisit assumptions about how humans first began to record speech, count goods, and formalize laws. The 39 distinct signs on this stone suggest a community that invested in the abstraction required to turn sounds or ideas into repeatable marks, a cognitive leap that has transformed societies across millennia. In that sense, the tablet is not just a regional curiosity but part of a broader story about how writing emerges, evolves, and sometimes disappears without leaving direct descendants.

The discovery also resonates with ongoing efforts to preserve and study endangered and lesser documented languages today. Institutions that curate historical collections, including specialized archives of agricultural and scientific records, have long shown how fragile written heritage can be when it is not systematically cataloged. One such collection of agricultural experiment station materials, preserved in a digital exhibit that organizes items by series and tags, illustrates how easily technical documents can vanish from public view without deliberate archiving, a point underscored by the structured metadata in a set of archival records. In a different domain, librarians and information specialists who document the evolution of medical literature, as reflected in a detailed issue of the Journal of the Medical Library Association, confront similar questions about how knowledge is recorded, indexed, and made legible to future readers. The Georgian tablet, with its compact but enigmatic script, sits at the intersection of those concerns, a small stone that challenges us to consider how much of humanity’s written past still lies unread beneath the ground.

More from MorningOverview