For decades, the search for life beyond Earth has focused on distant exoplanets and the rusty plains of Mars. Now, a small icy world in orbit around Saturn is emerging as one of the most compelling places in the Solar System where alien organisms might actually exist. Mounting evidence from spacecraft data and new analyses of frozen spray suggests that at least one Saturn moon could be not just habitable in theory, but chemically primed for biology right now.

Scientists are converging on a picture of a hidden ocean world, warmed from within and venting its secrets into space in the form of ice grains and vapor that spacecraft have already flown through. As researchers refine what they know about this environment and prepare new missions to sample it directly, the case that this moon could harbor life is no longer a fringe idea. It is becoming a central test of whether biology is a common outcome when rock, water and energy come together.

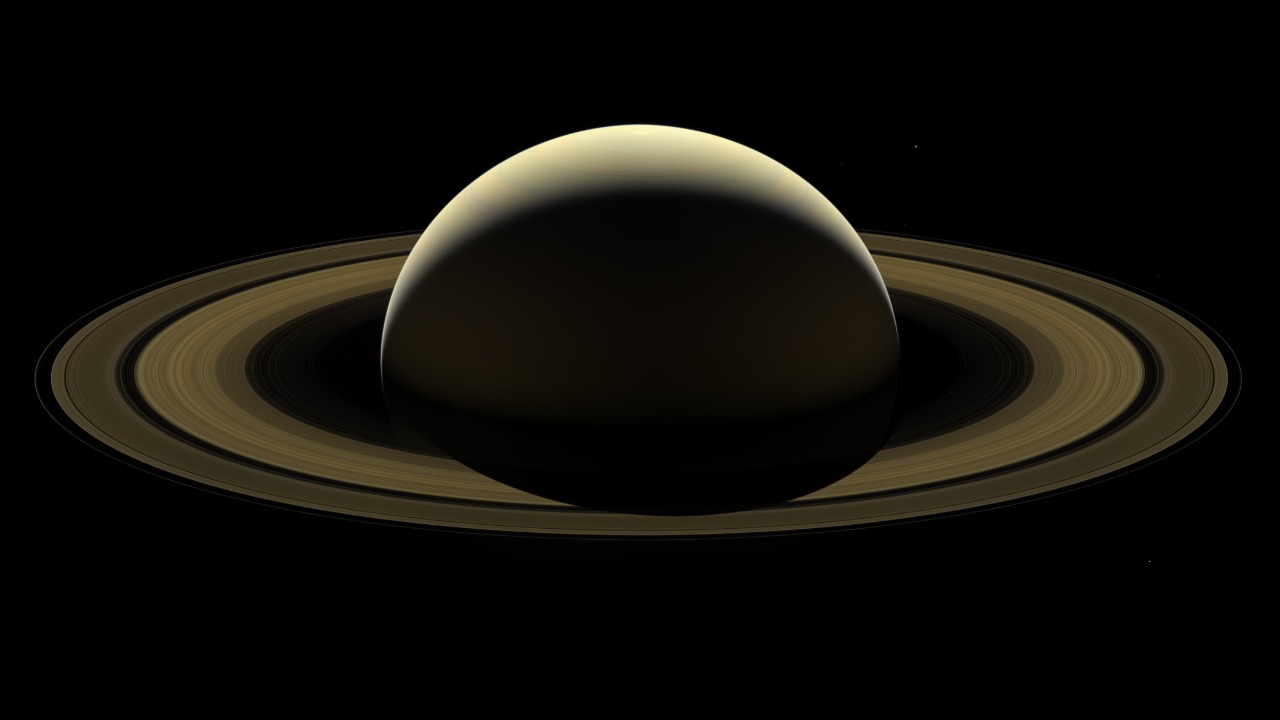

The Saturn system’s unlikely new frontrunner

Saturn has long been a showpiece of the outer Solar System, but its entourage of moons is now stealing the spotlight. Among them, Enceladus and Titan have emerged as prime candidates for habitability, with Enceladus in particular looking like a compact, efficient factory for the chemistry of life. Enceladus is a small moon of Saturn that hides a global ocean beneath an icy crust, yet still manages to blast material from that ocean into space through towering plumes at its south pole.

Those plumes have transformed Enceladus from a curiosity into a serious contender in the search for biology. Earlier work with the Cassini spacecraft showed that the jets contain water, salts and simple organics, but more recent analyses have expanded the catalog of complex molecules and strengthened the case that the subsurface sea is chemically rich. When I look across the new data, the pattern is clear: this is not a dead, frozen world, but a dynamic ocean environment that keeps sending fresh samples into space for us to catch.

Fresh ocean spray and “phenomenal” clues

The most striking new hints come from what researchers describe as fresh ocean spray erupting from Enceladus. As Cassini flew through the south polar plumes, it collected ice grains that were later reanalyzed with more sophisticated techniques, revealing what one team called the strongest life signs yet in the moon’s ejecta. Those grains, sourced from the ocean and blasted through icy vents into Cassini’s path, contained a suite of organic compounds and salts that point to active water–rock interactions at the seafloor, according to work highlighted in a study of Fresh ocean spray from Enceladus.

Another analysis of Cassini data has been described by scientists as “Phenomenal,” arguing that Enceladus now ticks all the boxes for a habitable environment. That work, which examined the composition of the plumes in detail, concluded that the moon’s ocean contains the essential ingredients for life, including organic molecules, liquid water and likely sources of chemical energy. The researchers behind this Phenomenal new evidence argue that the combination of these factors makes Enceladus one of the most promising places anywhere to look for living systems beyond Earth.

What Cassini’s legacy really tells us

Behind the headlines, the technical story is just as compelling. Fresh analysis of Cassini data has shown that the spacecraft did more than simply photograph a pretty plume; it effectively sampled both the surface and the jets, giving scientists a direct chemical fingerprint of the ocean below. By reprocessing measurements from Cassini’s instruments, researchers have been able to reconstruct the composition of the ice grains and vapor, revealing not only water and salts but a growing list of organic molecules that are consistent with hydrothermal activity. This deeper look at fresh analysis of Cassini data underscores how much information was hiding in the mission’s archives.

Other teams have focused on the structure of the plumes themselves, using Cassini’s flyby trajectories to infer how material moves from the ocean through fractures in the ice. The emerging picture is of a world where the ocean is in direct contact with a rocky core, generating chemical gradients that life could exploit, then venting that processed water into space. When I weigh those findings against what we know about Earth’s own deep ocean vents, the parallels are hard to ignore: both environments feature water, rock, and energy in close quarters, and both produce complex chemistry that could feed microbes.

Enceladus in the wider family of ocean worlds

Enceladus is not the only icy moon in the running, and that context matters. Europa, a moon of Jupiter, has long been a favorite target for astrobiologists, and recent radiation modeling has suggested that its surface may be more accessible than once feared. The findings by Nordheim and his colleagues, often referred to collectively as Nordheim and his team, indicate that Europa’s ice shell could preserve biosignatures within reach of future landers, which has helped swing that moon back toward the top of mission priority lists.

Yet even in this competitive field, Enceladus stands out because it does something Europa does not: it sprays its ocean into space in a way that spacecraft can sample without drilling. The 2023–32 Planetary Science and Astrobiology Decadal Survey explicitly identified the search for life on icy moons such as Europ and Enceladus as a central goal, emphasizing the need to capture and analyze compounds that may carry evidence of biology. That Planetary Science and Astrobiology Decadal Survey has effectively put Enceladus on equal footing with Europa, and in some ways ahead, because the technical path to sampling its ocean is so much clearer.

Titan: a second, stranger laboratory

While Enceladus grabs attention for its ocean, Titan offers a very different kind of experiment in habitability. Titan, Saturn’s largest moon, is a strange, alien world, Covered in rivers and lakes of liquid methane, icy boulders and dunes of organic sand beneath a thick, hazy atmosphere. Researchers studying Titan’s climate and chemistry have concluded that it could harbor life, but likely only in very small amounts, given the extreme cold and the unusual solvents involved. A detailed study of how Titan could harbor life suggests that any organisms there would have to be adapted to methane lakes rather than water oceans.

Even so, Titan continues to be a source of fascination for researchers, with some arguing that its chemistry could offer new insights into how life began on Earth. Earlier work has already shown that complex organic molecules form in Titan’s atmosphere and settle onto the surface, creating a natural laboratory for prebiotic chemistry. That is one reason Titan has been selected for a dedicated rotorcraft mission, and why scientists see it as a place that could support life or at least preserve the steps that lead up to it. As one analysis of Titan insights into life on Earth notes, the moon’s combination of methane weather and organic-rich dunes makes it a natural analog for early Earth’s atmosphere and surface chemistry.

Dragonfly and the race to sample Titan directly

To turn Titan from theory into data, NASA is preparing an ambitious rotorcraft mission called Dragonfly. This nuclear-powered drone will hop across Titan’s surface, sampling dunes, impact craters and possibly ancient lakebeds to map out the distribution of organic molecules and search for signs of prebiotic chemistry. The mission’s official description emphasizes that Dragonfly is designed to investigate the chemical processes that could lead to life, taking advantage of Titan’s thick atmosphere and low gravity to fly from site to site in a way no previous planetary mission has attempted.

Dragonfly’s science goals are not limited to Titan itself. By exploring a world where complex organics rain from the sky and collect in liquid methane lakes, the mission will test ideas about how life might arise in environments very different from Earth’s. If Dragonfly finds that Titan’s chemistry naturally assembles building blocks like amino acids or membrane-like structures, it will strengthen the argument that life is a common outcome in the universe wherever the right ingredients are present. In that sense, Titan becomes a counterpoint to Enceladus: one world offers a water ocean that looks familiar, the other a hydrocarbon landscape that stretches our definition of habitability.

Is there really an ocean under Titan’s ice?

One open question has been whether Titan, like Enceladus, hides a global water ocean beneath its crust. A recent NASA study suggests that Titan may not possess a global ocean, at least not in the way some models once envisioned. The researchers behind that work argue that gravity and rotation data are more consistent with a patchy or regionally confined subsurface sea, rather than a single continuous layer of water encircling the moon. Yet they are careful to add that, “While Titan may not possess a global ocean, that doesn’t preclude its potential for harboring basic life forms, assuming that life can adapt to the unique conditions present, whether it is in the subsurface or on the surface.” That nuanced view is captured in the While Titan study, which reframes Titan as a more complex, layered world.

For astrobiology, the implication is that Titan may host multiple potential habitats, from methane lakes at the surface to pockets of water-rich material deeper down. That complexity complicates mission design, since sampling a buried ocean is far harder than flying through a plume, but it also broadens the range of possible life strategies. If basic organisms can survive in hydrocarbon lakes or briny subsurface reservoirs, Titan could still be a living world, just one that looks nothing like Earth. I see that as a reminder that habitability is not a single checklist but a spectrum, and that our instruments need to be flexible enough to catch life in forms we might not anticipate.

Europe’s bold plan to chase alien life at Saturn

As the scientific case for Enceladus has strengthened, space agencies have begun sketching missions that would go back and sample the plumes with instruments built specifically to hunt for biology. The European Space Agency, often shortened to Esa, is now planning a mission explicitly aimed at searching for alien life in the Saturn system, with a particular focus on flying through Enceladus’s jets. Reporting on this effort describes how The European Space Agency wants to send a spacecraft that can capture and analyze ice grains in real time, looking for complex organics, isotopic patterns and other signatures that would be hard to explain without biology. That ambition is laid out in detail in coverage of how a Saturn moon could harbour alien life, which notes that Dec discussions inside Esa have moved from abstract concepts to concrete mission designs.

One of the most striking aspects of this proposed mission is its confidence. Scientists involved in the planning argue that Enceladus is not just theoretically habitable but may already host microbial ecosystems similar to those found in Earth’s deep ocean vents. They hope to sample jets of water spouting from the south pole and then compare the chemistry to what is known from organisms living in volcanic vents on our own seafloor. As Scientists have explained, the goal is not simply to detect generic organics but to look for patterns that match biological processing, such as specific chains of amino acids or cell-like structures frozen in the ice grains.

Stronger evidence, but still short of a smoking gun

Even with all these tantalizing clues, researchers are careful to distinguish between habitability and confirmed life. The discovery of more complex organic molecules in Enceladus’s plumes significantly expands the range of chemistry known to exist there, but it does not yet prove that any of those molecules are being assembled or maintained by living cells. A recent study that broadened the catalog of organics on Enceladus emphasized that the key is how those compounds are distributed and whether they show patterns that are hard to explain through simple geochemistry. That work, which framed the findings as more evidence that one of Saturn’s moons could harbor life, underscores how close the field is to a major breakthrough, yet how cautious it must remain.

Other analyses have focused on the physical properties of the ice grains themselves, looking for textures or inclusions that might indicate biological structures. So far, the results are intriguing but ambiguous, with some grains showing complex internal patterns that could be mineralogical or biological in origin. When I weigh these findings, I see a field that is deliberately holding itself to a high standard, insisting on multiple independent lines of evidence before declaring victory. That is why future missions are being designed to carry instruments capable of imaging individual particles, sequencing organic fragments and measuring isotopic ratios, all in the hope of turning suggestive chemistry into a clear biological signal.

Nature Astronomy and the case for a living ocean

One of the most influential recent studies of Enceladus’s ice grains was published in Nature Astronomy, and it has helped crystallize the argument that the moon’s ocean is not just wet but chemically active. By examining fresh ice from Saturn’s moon Enceladus, the researchers found signatures consistent with ongoing hydrothermal reactions at the seafloor, including mineral assemblages and organic patterns that match what is seen near Earth’s mid-ocean ridges. The authors of that work concluded that the findings add to growing evidence that Enceladus could be one of the most promising places in the Solar System to search for life, and they explicitly called for a dedicated mission to explore the moon up close. Those conclusions are summarized in coverage of Nature Astronomy findings on fresh ice.

For me, the power of that study lies in how it connects Enceladus to environments we already know can support life. On Earth, hydrothermal vents host dense communities of microbes and animals that thrive without sunlight, relying instead on chemical energy from reactions between seawater and hot rock. If Enceladus has similar vents on its seafloor, as the Nature Astronomy analysis suggests, then it is reasonable to think that comparable ecosystems could exist there as well. That does not guarantee that life has actually taken hold, but it does mean that the physical and chemical conditions are not exotic or marginal; they are directly analogous to habitats where life is already known to flourish.

Public fascination and the next wave of missions

The scientific debate is unfolding alongside a surge of public interest, fueled in part by accessible explainers and podcasts that translate technical findings into vivid stories. One widely shared video framed the latest Cassini results as NASA just finding signs of life on Saturn’s moon Enceladus, emphasizing that the ice contains the stuff life is made of and that there is a whole ocean hiding under the ice. That narrative, captured in a NASA Just Found Signs explainer, has helped cement Enceladus in the public imagination as a place where something might already be swimming in the dark.

Podcasts and news segments have also leaned into the mystery, with one episode titled “Alien Clues? Saturn’s Moon Just Got More Mysterious!” walking listeners through the latest plume chemistry and what it might mean for life. That show, part of a series that promises unique and interesting stories, uses Enceladus as a gateway to discuss how scientists define life and what kinds of evidence would be convincing. The Alien Clues? discussion underscores how the moon has become a cultural touchstone for the broader question of whether we are alone, and it reflects a growing expectation that the next generation of missions will finally deliver a definitive answer.

Why Enceladus now sits at the center of astrobiology

All of this new evidence has reshaped how mission planners think about priorities. The 2023–32 Survey period has already seen a shift toward so-called ocean worlds, and Enceladus is now firmly in that inner circle. Investigations into ocean worlds have highlighted how capturing and analyzing compounds that may carry evidence of biology is essential, and Enceladus offers a uniquely straightforward way to do that by flying through its plumes. A recent overview of investigating ocean worlds makes clear that Enceladus, Europ and Titan are now seen as complementary targets, each probing a different slice of the habitability spectrum.

European planners have been especially vocal about the stakes. In one detailed report, Sarah Knapton Science Editor described how senior scientists at The European agency argued that it is a very strong speculation that Enceladus is habitable, and that if life does exist there, sampling the plumes could reveal something moving under our microscope. That vivid phrase, drawn from coverage of how a Saturn moon could harbour alien life, captures both the excitement and the caution that define this moment. The evidence is strong enough to justify bold missions, but the final verdict will only come when a spacecraft flies through those plumes with instruments tuned not just to chemistry, but to biology itself.

More from MorningOverview