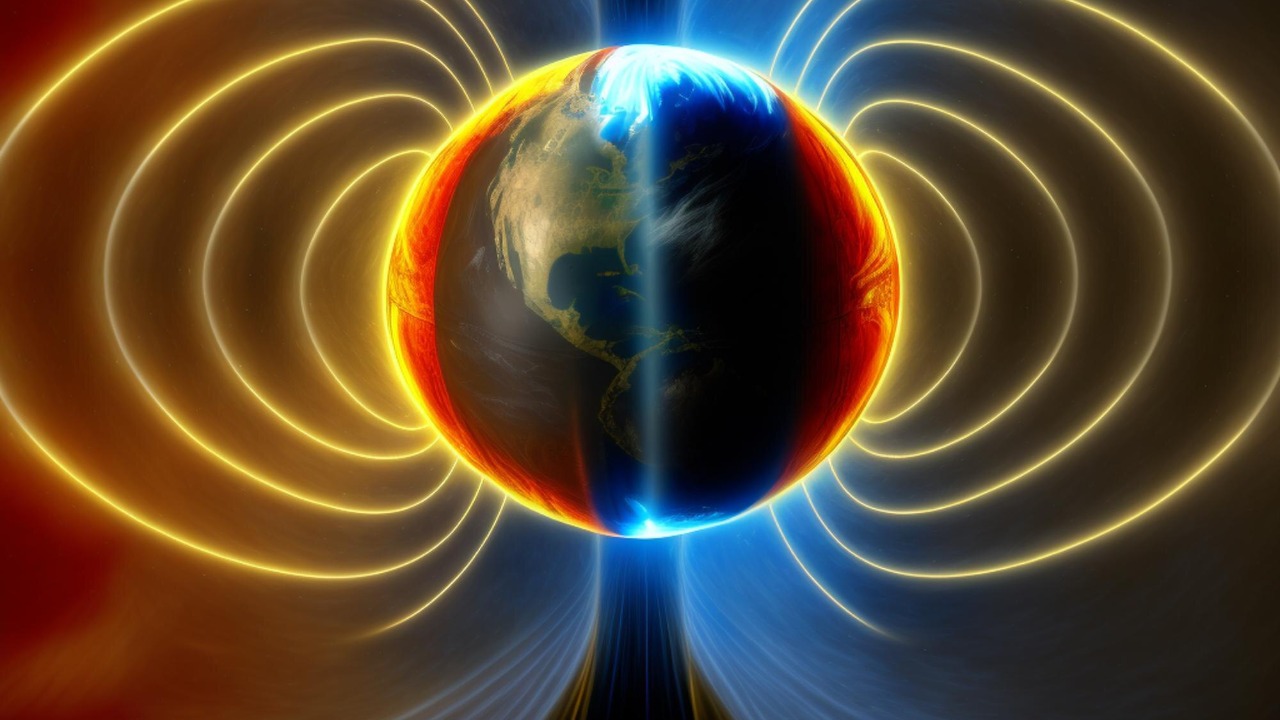

For more than a century, engineers have chased new ways to turn the planet’s natural motions into usable power, from tides to geothermal heat. Now a small group of physicists says Earth’s own magnetic field and rotation could be coaxed into generating electricity directly, using a device that behaves less like a traditional generator and more like a carefully tuned piece of planetary circuitry. If the concept holds up, it would not replace solar panels or wind farms, but it could open a niche class of ultra‑reliable, ultra‑low‑power systems that quietly sip energy from the spinning Earth itself.

The idea sounds like science fiction, yet it rests on sober electromagnetic theory and a tabletop experiment that has already produced a measurable voltage. The early prototypes only yield tiny outputs, measured in microvolts, but they challenge long‑standing assumptions about what Earth’s rotation through its own magnetic field can and cannot do. I see this as less a shortcut to “free electricity” and more a test of how far we can push the physics of a rotating, magnetized planet.

From thought experiment to tabletop hardware

The story starts with a theoretical puzzle: could a conductor fixed to Earth, and therefore rotating with it, draw power from the planet’s motion through its own magnetic field without violating basic conservation laws. In 2016, researchers argued that under the right conditions, a specially shaped conductor embedded in Earth’s field could in principle generate a small but continuous current as the planet spins, even though the rotation only slows by less than 10 milliseconds per century according to their calculations of Earth. That work framed the planet itself as part of a giant electrical circuit, with the magnetic field acting as a kind of stator and the conductor as a rotor that never stops moving.

For years the idea sat mostly on paper, in part because many physicists believed that any such device would be thwarted by the same arguments that limit conventional generators attached to a rotating magnetized body. The new twist came when the same team proposed a conducting soft magnetic object with specific topological and material properties that could sidestep those constraints. By shaping the conductor into a cylindrical shell and embedding it in a carefully controlled magnetic environment, they argued, it should be possible to tap a tiny but steady electromotive force from Earth’s rotation without relying on external moving parts.

The experiment that squeezed 17 microvolts from the planet

The leap from equations to experiment arrived earlier this year, when the group reported that they had actually measured a voltage produced by a prototype device designed to mimic Earth’s rotation through its own field. In a controlled setup, they rotated a conducting cylinder within a magnetic field configured to resemble the relevant part of the geomagnetic environment and detected a signal of 17 microvolts, a level so small it sits near the edge of what precision instruments can reliably pick out from noise. As one account put it, Scientists Turned the Earth and its Rotation Into a measurable trickle of Microvolts of Electricity, and That Could Be Revolutionary precisely because it validates the underlying mechanism.

On its own, 17 microvolts is not going to light a bulb, let alone power a home, but in experimental physics the first priority is proving that a phenomenon exists at all. The team’s measurements show that a conductor with the right geometry, moving through a magnetic field configured to match Earth’s, can indeed produce a continuous voltage without any external energy input beyond the rotation itself. That result, which the researchers attribute to their specially engineered soft magnetic material, gives them a concrete starting point for scaling up the effect, even if the path from microvolts to practical devices remains long and technically demanding.

How the device actually works

At the heart of the new method is a conducting soft magnetic object shaped into a cylindrical shell, designed so that its internal magnetic configuration interacts with the surrounding field in a very specific way. When this shell rotates within a magnetic field aligned to mimic Earth’s, charges inside the conductor experience forces that separate them slightly, creating a potential difference between different parts of the cylinder. According to the researchers, the object’s topological and material properties allow it to circumvent the theoretical constraints that usually prevent a rigid conductor attached to a rotating magnetized body from generating net power, a point they emphasize in their description of the conducting soft magnetic object.

In practical terms, the apparatus looks less like a wind turbine and more like a precision lab instrument, with the cylindrical shell mounted on a rotating platform and surrounded by coils that generate the required magnetic field. The researchers carefully position their specialized cylinders so that the rotation and field lines align in the way their theory demands, then use sensitive electronics to measure the resulting voltage. Earlier coverage of the work notes that the team experimented to see if this configuration could capture electricity from Earth’s rotational dynamics at all, and that they only saw a signal when they had carefully positioned their specialized cylinders within the artificial field.

Why some physicists remain unconvinced

Not everyone in the physics community is ready to accept that a device fixed to Earth can draw net power from the planet’s rotation through its own magnetic field. For decades, standard arguments in electromagnetism have held that any such scheme would either violate energy conservation or simply repackage energy from some other source, such as temperature gradients or external currents. Critics of the new work suggest that the observed voltage might be an artifact of the experimental setup, or that the device is in fact tapping into a more conventional phenomenon, such as subtle variations in the applied field or mechanical friction, rather than Earth’s rotation itself.

The debate has been sharpened by the researchers’ claim that they have found a loophole in those long‑standing arguments. As one analysis of the controversy notes, the discussion centers on whether the complex calculation used to justify the device’s operation really captures all the relevant physics, or whether some hidden assumption breaks down in the real world. In that account, the section titled Planet power describes how But Chyba and his colleagues argue that, Using their mathematical framework, the device can indeed extract a tiny amount of energy from Earth’s rotation, while skeptics counter that the signal might instead arise from some more mundane phenomenon, such as temperature variations in the apparatus.

What “free electricity” really means in this context

The phrase “free electricity” has a way of attracting attention, and some coverage of the new device leans into that language, suggesting that scientists have discovered a way to pull power directly from Earth’s magnetic field without burning fuel or catching sunlight. In one widely shared explainer, the narrator asks what if I told you that scientists have just demonstrated a device that generates electricity directly from the Earth, framing the result as a kind of technological magic trick. The reality is more prosaic: the energy still comes from the gradual slowing of Earth’s rotation, and the amounts involved are so small that they barely register on planetary scales, as the earlier theoretical work that quantified how Earth slows by less than 10 milliseconds per century already made clear.

From my perspective, the more interesting question is not whether the electricity is “free” in some philosophical sense, but whether the method can be engineered into something robust and useful. The video that describes how Scientists DISCOVER FREE Electricity from Earth’s Magnetic field is careful to note that the current devices are laboratory prototypes, and that the power levels are tiny compared with even a modest solar cell, despite the excitement around Scientists DISCOVER FREE Electricity from Earth’s Magnetic field in Aug. The real value of the work lies in expanding the menu of physical effects that engineers can draw on, not in promising a shortcut to limitless energy.

Scaling up: from microvolts to real‑world uses

Turning 17 microvolts into something that can power actual hardware is a formidable engineering challenge, but it is not unprecedented in the broader world of energy harvesting. Many existing technologies, from piezoelectric sensors to thermoelectric generators, start with similarly tiny signals and then rely on clever electronics to accumulate and manage that energy over time. In the case of the Earth‑rotation device, the immediate goal is not to run a refrigerator, but to see whether the voltage can be increased by optimizing the cylinder’s geometry, materials, and magnetic environment, and then paired with ultra‑low‑power electronics that can operate on microwatts or less.

One potential application that has already been floated is the idea of ultra‑long‑life sensors that never need a battery change, instead sipping power continuously from the planet’s rotation. Coverage of the project notes that the team’s apparatus, built around a cylindrical shell made of a carefully chosen soft magnetic conductor, could eventually unlock an entirely new option for clean energy at the scale of remote instruments and monitoring devices. As one report put it, the same configuration that produced the initial microvolt‑level signal could, in principle, be refined into a platform for ultra‑long‑life sensors that draw their power from Earth’s rotation rather than from chemical batteries or intermittent sunlight.

How it fits into the broader clean‑energy puzzle

Even if the new device never scales beyond niche applications, it sits within a larger wave of research that looks for power in overlooked corners of the environment. In recent years, scientists have built experimental systems that harvest energy from raindrops, ambient radio waves, and even falling snow, each one targeting situations where conventional solar or wind power is impractical. One such project demonstrated a snow‑based generator that produces electricity when flakes land on a specially designed surface, a concept that remains a proof of concept because its power output is still low. As one of the researchers behind that work put it, But their invention is still a “proof of concept” experiment for now, since its power output remains low, even though it opens a new direction in this field of research, a point highlighted in the discussion of whether snow be the next source of clean energy.

I see the Earth‑rotation generator as part of that same ecosystem of experimental ideas, where the goal is not to replace gigawatt‑scale power plants but to fill specific gaps in the energy landscape. Just as microbial fuel cells can power small sensors in remote or underwater environments despite their low potential and current production capacities, a device that draws microvolts from Earth’s rotation could serve in situations where reliability and longevity matter more than raw power. A review of power management systems for microbial fuel cells notes that this technology is lagging behind to find practical applications, since the MFCs with scientific advances made so far still struggle with their low potential and current production capacities, a challenge that also applies to any future power management systems built around Earth‑rotation devices.

Inside the lab: rotation, symmetry and speed

To understand why the new device works at all, it helps to picture Earth as a giant magnet with field lines that are roughly, though not perfectly, aligned with its axis of rotation. The part of the field that is axially symmetric is the one that matters most for this effect, because it stays fixed relative to the spinning planet. In one technical explainer, a researcher describes how we are moving through that part of the field at 350 m/s, a speed that sets the scale for the forces acting on charges in a conductor attached to Earth. That same discussion, which walks through the geometry of the setup, emphasizes that the generator’s behavior depends critically on how the conductor is oriented relative to the field lines that define part of the Earth’s field that is um axially symmetric we’re moving through it at 350 m per second in Sep.

In the laboratory, the team cannot literally spin Earth faster or slower, so they simulate the relevant conditions by rotating their cylindrical shell within a magnetic field that reproduces the key features of the geomagnetic environment. By adjusting the rotation rate and field strength, they can explore how the generated voltage scales with each parameter, testing whether it behaves as their theory predicts. The early results, including the 17 microvolt signal, suggest that the effect does track the expected dependencies, although the measurements are delicate enough that even small sources of noise or asymmetry can complicate the picture, which is one reason the broader physics community is scrutinizing the work so closely.

What comes next for this planetary generator idea

For now, the Earth‑rotation generator sits at the intersection of bold theory and fragile experiment, with both supporters and skeptics watching to see whether the initial results can be replicated and extended. The researchers behind the work are already planning more refined prototypes that use improved materials and more precise magnetic control, in hopes of boosting the output beyond the microvolt range and clarifying exactly how the device interacts with Earth’s field. If those efforts succeed, the next step would be to design power electronics that can harvest and store the tiny trickle of energy in a form that real‑world devices can use, a challenge that echoes the hurdles faced by other ultra‑low‑power technologies.

At the same time, the broader narrative around the project is likely to evolve as more data comes in and as other groups attempt their own versions of the experiment. Reports that Scientists pull electricity directly from Earth’s rotation capture the excitement of a device that seems to draw power from a planetary motion that continues through it all the time, but they also risk overselling what is, at this stage, a delicate and highly specialized setup. As I see it, the most responsible way to frame the work is as a provocative demonstration that Earth’s rotation and magnetic field can, under the right conditions, be coaxed into producing a measurable voltage, a result that invites both deeper theoretical scrutiny and creative engineering, as highlighted in the description of how Scientists pull electricity directly from Earth’s rotation in Dec.

More from Morning Overview