A burst of high-energy radiation has struck Spain’s newest military communications satellite, jolting a flagship program that Madrid has promoted as a cornerstone of its secure links with deployed forces. The incident has forced engineers to lean on backup systems and raised fresh questions about how well even the most advanced spacecraft can withstand the invisible hazards that fill near-Earth space.

What happened to the satellite is still being pieced together, but early indications point to a powerful “space particle” impact that briefly compromised part of its electronics during a critical maneuver. I see the episode as a revealing stress test for Europe’s space ambitions, exposing both the fragility of orbital hardware and the growing sophistication of the contingency plans designed to keep it working.

Spain’s flagship satellite takes an unexpected hit

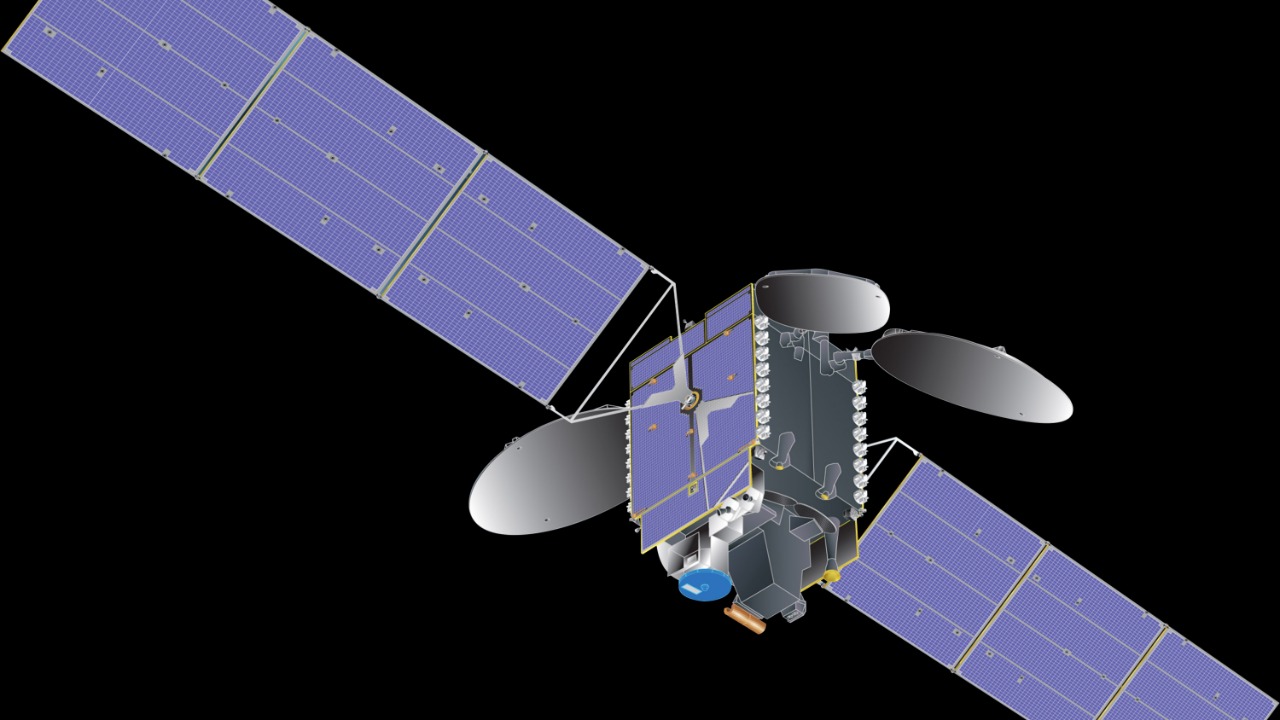

Spain’s new military communications platform, Spainsat NG-II, was supposed to spend its first months in orbit quietly proving itself, not fighting off a blast of radiation. Instead, during a transfer phase that should have been routine, a high-energy particle slammed into the spacecraft and triggered what engineers describe as an “external impact” on its systems. The event did not shatter solar arrays or rip through fuel tanks, but it did inject enough energy into sensitive components to disrupt normal operations at a moment when the satellite was still settling into its planned orbit.

In MADRID, the company responsible for the satellite’s space segment, Indra Group, confirmed that Spainsat NG-II had suffered this external impact and that the anomaly occurred while the spacecraft was being repositioned. According to Indra Group, the hit compromised part of the satellite’s functionality during the transfer phase, forcing teams to switch to pre-planned backup modes. That confirmation matters because it rules out a software bug or ground control error and squarely points to the harsh environment around Earth as the culprit.

Why a “space particle” can cripple a billion-euro asset

To anyone used to thinking of satellites as rugged machines, the idea that a single particle can cause trouble sounds counterintuitive. In reality, the electronics that make a platform like Spainsat NG-II so capable are also exquisitely sensitive to stray energy. A high-energy proton or heavy ion can plow into a microchip, deposit charge in the wrong place, and flip a bit in memory or logic. In the best case, that produces a harmless glitch. In the worst case, it can lock up a processor, corrupt a configuration file, or even permanently damage a component that has no easy workaround.

Military communications satellites are hardened against this kind of radiation, but there are limits to how much shielding and redundancy can be packed into a spacecraft without making it too heavy or too power hungry. When Indra Group describes an external impact that compromised functionality during a transfer phase, it is describing exactly the kind of scenario designers fear: a particle strike at a time when the satellite is executing a complex sequence of maneuvers and software-controlled steps. In that window, a single upset can cascade into a broader anomaly if it hits the wrong subsystem at the wrong moment.

Indra’s contingency playbook moves into action

The real test of a satellite program is not whether it avoids every anomaly, but how it responds when something goes wrong. In this case, Indra Group did not wait for the spacecraft to sort itself out. Engineers activated contingency plans that had been rehearsed on the ground, shifting Spainsat NG-II into safer configurations and rerouting tasks to redundant hardware. Those procedures are designed precisely for events like a high-energy particle strike, when the priority is to stabilize the platform first and diagnose the root cause later.

By confirming that contingency plans were activated after the external impact, Indra Group signaled that the incident was serious enough to warrant a structured response but not catastrophic enough to write off the satellite. The company’s statement from MADRID framed the anomaly as a contained event in the transfer phase, not a systemic failure of the Spainsat NG program. That distinction matters for Spain’s defense planners, who rely on Spainsat NG-II and its twin, Spainsat NG-I, to carry secure traffic for government and military users and cannot afford a prolonged outage.

What the hit means for Spain’s secure communications

For Spain’s armed forces, the timing of the impact is almost as important as the physics behind it. Spainsat NG-II is part of a new generation of satellites meant to replace older platforms and expand coverage for deployed units, maritime operations, and diplomatic links. Any disruption during the early transfer phase risks delaying the point at which the satellite can be declared fully operational and integrated into day-to-day communications planning. Even a short-lived anomaly can force commanders to lean longer on legacy systems or allied networks.

Indra Group’s confirmation that the impact compromised functionality during the transfer phase suggests that some planned activities had to be paused or re-sequenced. In practice, that can mean postponing certain orbit-raising burns, delaying payload calibration, or holding off on handing over control from the manufacturer to the operator. For a military satellite, those delays translate into a slower ramp-up of encrypted channels and protected links that are supposed to give Spain more autonomy in how it routes sensitive traffic. The fact that contingency plans were ready and executed quickly is reassuring, but it does not erase the operational friction that comes with an unexpected hit.

Space weather, debris, and the crowded orbital neighborhood

Although Indra Group has described the event as an external impact, the label “space particle” covers a range of possible culprits. High-energy protons from solar storms, trapped particles in Earth’s radiation belts, and even secondary particles generated when cosmic rays hit the spacecraft structure can all produce the kind of upset seen on Spainsat NG-II. The transfer phase often takes a satellite through regions where these particles are more intense, especially near the Van Allen belts, which makes that period particularly risky for sensitive electronics.

At the same time, the term external impact inevitably raises questions about orbital debris. Even a tiny fragment of metal or paint chip traveling at several kilometers per second can deliver a punch far beyond its size. In this case, the description of a high-energy particle and the lack of reported structural damage point more toward a radiation event than a debris strike, but the distinction is not academic. If debris were involved, it would add to growing concerns about the safety of crowded orbits and the need for better tracking and mitigation. For now, the available information ties the anomaly to the broader category of space environment hazards that every operator must factor into mission design.

Lessons from past satellites that met space at full force

Spainsat NG-II is not the first spacecraft to be rattled by the environment it operates in, and it will not be the last. Earlier missions have shown how even well-designed satellites can be pushed to the edge by radiation, thermal extremes, or micrometeoroid hits. The Japanese X-ray observatory Suzaku, for example, spent years studying high-energy phenomena in the universe while itself being battered by the same kinds of particles that now trouble Spain’s new satellite. Its instruments and electronics were built to cope with intense radiation, yet its operators still had to manage gradual degradation and occasional anomalies as the mission aged.

Accounts of the Suzaku satellite describe how the Copernical Team tracked the observatory’s performance and how its experience fed into later European projects, including Galileo navigation satellites that rode Ariane launchers to strengthen Europe’s resilience. Those programs underline a simple point that applies directly to Spainsat NG-II: every mission is both a service provider and a data point in a long-running effort to understand how hardware behaves in orbit. When a high-energy particle knocks a modern satellite off script, engineers reach not only for contingency plans but also for the accumulated lessons of earlier spacecraft that have weathered similar storms.

How Europe’s space ambitions shape the response

Spain’s reaction to the Spainsat NG-II incident is unfolding against a broader European backdrop in which space is increasingly treated as critical infrastructure. Programs like Galileo, launched on Ariane rockets to give Europe its own navigation system, were justified in part as a way to reduce dependence on foreign constellations. Spainsat NG fits the same logic for secure communications. A high-energy impact that compromises functionality, even temporarily, is therefore not just a technical hiccup but a reminder of how much political and strategic capital is now tied up in orbital assets.

That context helps explain why Indra Group moved quickly to confirm the external impact and highlight the activation of contingency plans. For European governments, transparency about anomalies is a way to maintain confidence in the broader project of building independent space capabilities. It also creates pressure to invest in more robust designs, better space weather forecasting, and closer coordination between civilian and military operators. The experience of earlier European missions, from Galileo to scientific observatories like Suzaku that informed later designs, will likely feed into post-incident reviews of Spainsat NG-II and shape how future satellites are hardened against similar events.

What comes next for Spainsat NG-II and its operators

In the near term, the priority for Indra Group and Spanish authorities is to verify that Spainsat NG-II has fully recovered from the impact and that no latent damage is lurking in its systems. That process typically involves exhaustive checkouts of power, propulsion, and payload subsystems, along with careful analysis of telemetry from the moment of the anomaly. If the high-energy particle caused only transient upsets, engineers can gradually return the satellite to its planned sequence of maneuvers and begin the handover to routine operations.

Longer term, the incident will likely become a case study in how to manage high-energy events during critical mission phases. Designers may revisit shielding strategies, redundancy schemes, and software protections that can catch and correct bit flips before they cascade. Operators may refine their procedures for transfer orbits, perhaps adjusting timelines to avoid known peaks in radiation exposure. For Spain, the episode is an unwelcome but valuable reminder that even a state-of-the-art platform like Spainsat NG-II is at the mercy of the space environment, and that resilience in orbit depends as much on planning for the worst as it does on celebrating a successful launch.

More from Morning Overview