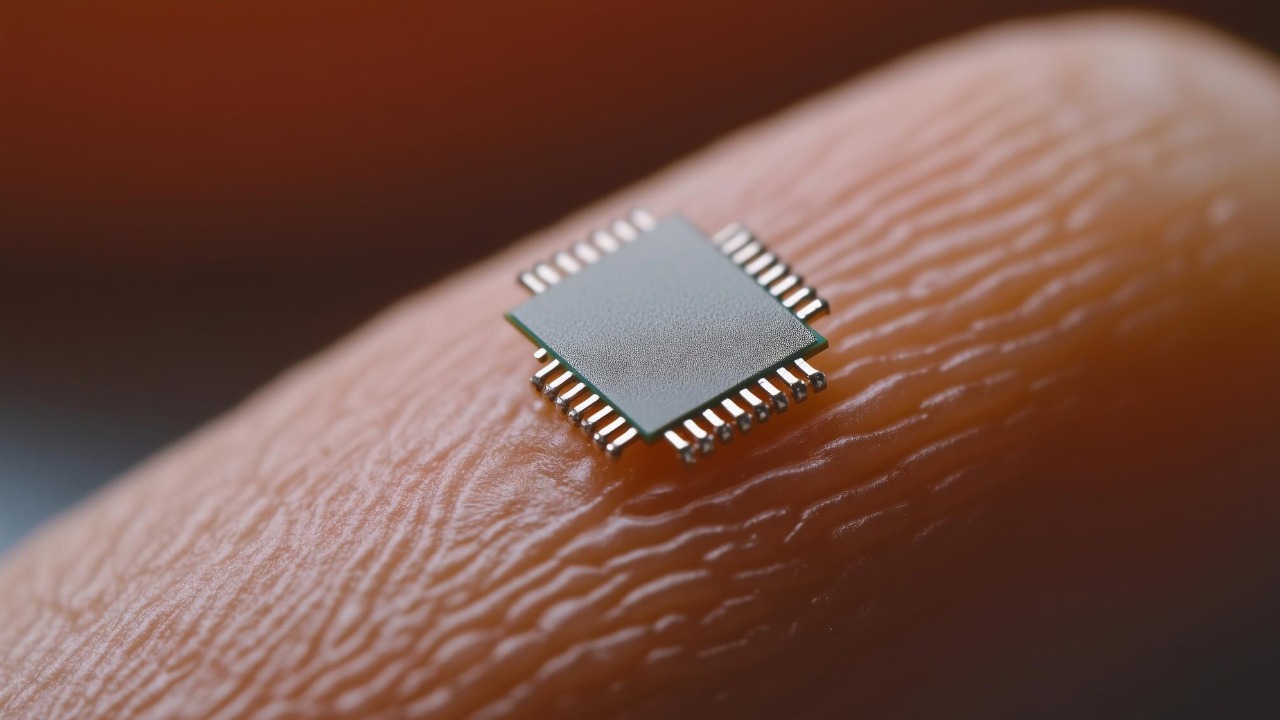

A device smaller than a grain of dust is emerging as a surprisingly powerful candidate to reshape how quantum computers are built and scaled. Instead of relying on room-filling optics and fragile lab setups, this new component promises to shrink some of the most complex control hardware onto a chip that looks almost trivial under a microscope. If it works as advertised, the path to practical, massively parallel quantum machines could run through a speck of silicon that barely registers to the naked eye.

Why quantum computers are stuck in the lab

Quantum computers are often portrayed as almost magical machines, but their current reality is far more cumbersome. To run even modest algorithms, researchers must orchestrate the behavior of individual qubits with exquisite precision, a process that, as one analysis of trapped-ion systems notes, involves performing careful control of the energy state of every qubit independently. When ions are spaced only about 5 micrometers apart, steering each one without disturbing its neighbors demands a forest of lasers, lenses, and feedback electronics that quickly becomes unmanageable as systems grow.

That complexity explains why most quantum processors still look more like experimental physics rigs than commercial products. A detailed overview of current platforms points out that a typical quantum processor is at an exploratory stage and takes up a lot of space, with the hardware that manipulates qubits consisting of lasers, lenses, and mirrors arranged in intricate optical benches. According to this assessment, the sophisticated optics needed to control qubits are a major reason why quantum setups remain bulky and fragile, a problem that a dust-sized device aims to solve by collapsing some of that infrastructure into a compact, integrated component.

The dust-sized device at the heart of the breakthrough

The new component attracting attention is a tiny on-chip structure designed to manipulate light with extreme precision, yet fabricated using the same industrial processes that build everyday electronics. Reporting on the advance describes a device smaller than a grain of dust that can be produced through the design of the CMOS-fabricated, resonantly enhanced architecture that modern chip foundries already understand. By leaning on complementary metal–oxide–semiconductor techniques, the same basic toolkit behind smartphone processors and laptop CPUs, the researchers sidestep the need for exotic manufacturing and instead ride on decades of semiconductor scaling.

What makes this speck of hardware so promising is not just its size, but its function. The component acts as a phase modulator for light, a tool that can imprint information onto photons or adjust their timing with high fidelity, which is exactly what large-scale quantum systems based on light need. A top-down image of the on-chip phase-modulator devices, captured with a microscope and credited to Top view photographer Andrew Leenheer, shows a dense array of structures that can, in principle, be tiled across a chip in huge numbers, each one nudging individual photons that carry the basic units of quantum information.

How a phase modulator unlocks scalable quantum optics

At the core of many quantum computing schemes that use light is the need to control the phase of photons, which determines how their wave-like properties interfere and combine. Traditional optical phase modulators are bulky devices that sit outside the chip, connected by fibers or free-space beams, and they consume significant power to achieve the necessary effect. The new dust-scale component instead integrates the phase modulation directly into the chip, using a resonantly enhanced structure that amplifies its impact so that a tiny electrical signal can produce a large optical response, a design choice that the description of the CMOS-fabricated architecture highlights as central to its efficiency.

By shrinking the modulator and embedding it in silicon, the researchers open the door to arrays of thousands or even millions of individually addressable optical elements, each one steering a photon in a slightly different way. A detailed account of the work notes that this tiny new device could enable giant future quantum computers by making it realistic to build phase modulators in huge numbers on a single chip, rather than wiring up discrete components one by one. In that reporting, the project is framed as a Tiny Chip Breakthrough Could Supercharge Quantum Computers, precisely because it turns a historically bulky function into something that can be replicated at semiconductor scale.

From room-sized optics to chip-scale control

To appreciate the significance of this shift, it helps to contrast the dust-sized device with the sprawling optical tables that dominate many quantum labs. Analyses of current quantum technology emphasize that the sophisticated optics needed to manipulate qubits consist of lasers, lenses, and mirrors that occupy entire racks or rooms, with each beam path carefully aligned and stabilized. One detailed discussion of how quantum technology is changing the world notes that, at present, a quantum processor is still at the exploratory stage and that the hardware controlling qubits consists of lasers, lenses, and mirrors that are difficult to miniaturize, a reality that keeps most systems confined to specialized facilities rather than data centers or office buildings.

By comparison, the new phase modulator is designed to sit directly on a chip, eliminating the need for many external optical components and the painstaking alignment they require. The top-down microscope image credited to Andrew Leenheer shows a device that looks more like a conventional integrated circuit than a physics experiment, with patterned waveguides and electrodes laid out in regular grids. If such structures can replace or at least drastically reduce the footprint of free-space optics, then quantum processors could begin to resemble the compact, sealed modules that power classical computing, rather than the delicate, open-air assemblies that dominate today.

Why CMOS fabrication matters for quantum scale-up

One of the most important aspects of the dust-sized device is that it is built using CMOS fabrication, the same industrial process that underpins the global semiconductor industry. The description of the design of the CMOS-fabricated, resonantly enhanced phase modulator stresses that it can be produced in standard foundries, which means it can, in principle, benefit from the same economies of scale and process refinements that have driven down the cost and size of classical chips. Instead of crafting each quantum component as a bespoke piece of lab equipment, engineers could order wafers full of identical devices, each one smaller than a grain of dust, ready to be integrated into larger systems.

That compatibility with existing manufacturing is not just a convenience, it is a strategic advantage in a world where access to advanced fabrication capacity and critical materials is increasingly contested. A survey of computing and math research trends notes that Critical Minerals Are Hiding in Plain Sight in U.S. Mines, and that researchers have identified how U.S. metal mines already contain many of the elements needed for high-tech applications. By designing quantum components that use familiar CMOS-compatible materials and processes, rather than exotic compounds that depend on fragile supply chains, the dust-sized device aligns quantum hardware with broader efforts to secure access to the minerals and manufacturing capacity that advanced electronics require.

The control problem: taming thousands of qubits

Even with better hardware, scaling quantum computers is ultimately a control problem. As systems grow from dozens to hundreds or thousands of qubits, the challenge is not only to keep each qubit coherent, but also to address each one individually without cross-talk. A detailed examination of trapped-ion quantum computing explains that Performing a quantum computation requires precisely controlling the energy state of every qubit independently, even when ions are only about 5 micrometers apart. That level of granularity is difficult to achieve with bulk optics and discrete electronics, which is why many current systems hit practical limits long before they reach the theoretical qubit counts that researchers envision.

The dust-sized phase modulator directly targets this bottleneck by offering a way to embed fine-grained control into the same chip that routes and processes quantum signals. Because each modulator is so small, designers can imagine placing one at every node where a photon interacts with the circuit, effectively giving each qubit or mode its own dedicated control knob. The reporting that frames the work as a Tiny Chip Breakthrough emphasizes that the device can be built in huge numbers, which is exactly what is needed when the goal is to manage thousands or millions of quantum channels in parallel. In that sense, the new component is less about raw computational power and more about the infrastructure that makes large-scale quantum operations feasible.

From experimental rigs to deployable quantum hardware

For quantum computing to move beyond demonstration projects and into real-world deployments, the hardware must become more compact, robust, and manufacturable. Analyses of the current state of quantum technology stress that processors are still at an exploratory stage, with setups that take up a lot of space and rely on delicate optical alignments that are vulnerable to vibration, temperature changes, and human error. One detailed discussion of how quantum technology is changing the world notes that, at present, a quantum processor is still at the exploratory stage and that the sophisticated optics needed to control qubits consist of lasers, lenses, and mirrors, a combination that is hard to package into a product that can be shipped, installed, and maintained like a conventional server.

By contrast, the dust-sized device is explicitly designed for integration into compact, chip-scale systems that can be replicated and deployed in volume. The description of the device smaller than a grain of dust highlights that it uses far less power than older tools need, a crucial factor when quantum hardware must operate inside cryogenic refrigerators or other constrained environments where every watt of heat is a liability. If phase modulation and other key optical functions can be handled by such efficient, CMOS-fabricated components, then the rest of the quantum stack can be engineered around standardized modules rather than custom lab gear, bringing the field closer to the kind of plug-and-play hardware that cloud providers and industrial users expect.

The road ahead for dust-scale quantum components

None of this means that a single dust-sized device will, on its own, deliver the fully fault-tolerant quantum computers that researchers ultimately want. The broader ecosystem still has to solve challenges in error correction, materials, cryogenics, and software, and many of those problems are only loosely connected to optical phase modulation. Yet the emergence of a CMOS-fabricated, resonantly enhanced phase modulator that is smaller than a grain of dust shows how quickly the hardware landscape is evolving, and how lessons from classical chip design can be repurposed for quantum systems. By turning a historically bulky function into something that can be stamped out by the million, the researchers behind this work have provided a template for how other quantum components might follow.

As I look across the reporting on current quantum platforms, from trapped ions spaced 5 micrometers apart to photonic circuits that rely on intricate optics, the pattern is clear: the future belongs to architectures that can compress complexity into scalable, manufacturable units. The dust-sized device that now sits at the center of this conversation is a vivid example of that trend, a reminder that sometimes the most consequential advances in computing come not from grand new theories, but from tiny pieces of hardware that quietly make the impossible practical.

Supporting sources: How quantum technology is changing the world.

More from MorningOverview