Cancer researchers have long treated genetic chaos and epigenetic rewiring as separate engines of disease, two parallel hallmarks that help tumors grow, spread, and resist treatment. Now a new wave of work is revealing that these forces are tightly intertwined, with chromosomal instability actively driving epigenetic changes that reshape how cancer cells behave. The emerging picture is that the genome’s physical architecture and its chemical “software” are locked in a feedback loop, and that loop may be one of the most powerful levers for stopping tumors in their tracks.

Instead of a simple list of hallmarks, scientists are starting to see cancer as a dynamic system where structural damage to chromosomes, shifts in gene regulation, and the surrounding microenvironment all reinforce one another. By tracing how these layers connect, researchers are uncovering vulnerabilities that were invisible when each hallmark was studied in isolation, from childhood brain tumors to aggressive melanomas and shapeshifting carcinomas.

The surprise connection between chromosomal chaos and epigenetic control

The most striking new insight comes from Research that set out to understand why some cancer cells are so unstable at the chromosomal level yet still manage to survive. Instead of finding a one-way street from DNA damage to random dysfunction, the team uncovered a direct mechanistic link between chromosomal instability and epigenetic changes that control which genes are turned on or off. In other words, the same forces that scramble chromosomes also appear to reprogram the chemical marks that sit on top of DNA, creating a coordinated shift in cell identity rather than pure genetic noise.

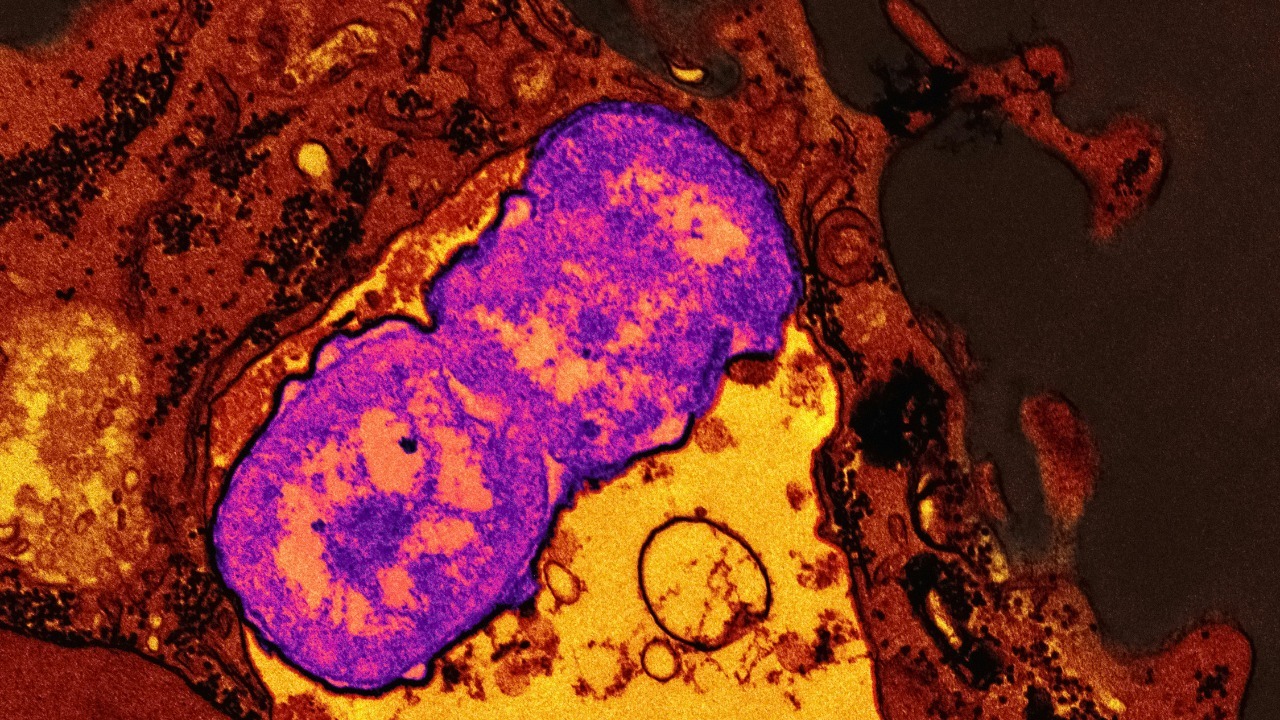

This work, spearheaded by MSK, showed that when chromosomes mis-segregate and break apart, the resulting stress does not just alter gene copy number, it also triggers widespread remodeling of chromatin and DNA methylation patterns. That remodeling can silence tumor suppressor genes or activate growth pathways, effectively converting structural damage into a new regulatory state that favors survival and adaptation. By tying chromosomal instability directly to epigenetic reprogramming, the Research spearheaded by MSK reframes two classic cancer hallmarks as parts of a single, self-reinforcing process.

Why chromosomal instability has always haunted cancer biology

To understand why this connection matters, it helps to recall how central chromosomal damage has been to cancer theory from the start. Cancer cells often carry both numerical and structural abnormalities of chromosomes, a pattern that was recognized more than a century ago and later tied to the idea that chromosomes are the physical carriers of heredity. Those abnormalities include extra or missing chromosomes, large deletions, and complex rearrangements that disrupt normal gene dosage and create novel fusion genes, all of which can drive uncontrolled growth.

Modern work has sharpened that picture by showing that Abnormalities in chromosome copy number and structure, collectively known as chromosomal instability, are not just byproducts of malignant growth but active contributors to it. The link between aneuploidy and cancer has been recognized for decades, and detailed analyses now show that ongoing chromosomal instability can fuel tumor evolution, therapy resistance, and metastasis by constantly generating new genetic variants. When I look at these findings alongside the new epigenetic data, the long-standing view of Abnormalities in chromosome copy number as a core cancer hallmark suddenly seems incomplete without considering how they reshape gene regulation too.

Epigenetics: the chemical tags that turn damage into new identity

If chromosomal instability is the hardware failure, epigenetics is the software rewrite that follows. Known as epigenetics, the mechanism works by adding chemical tags such as methyl groups on DNA, which influence whether genes are active without changing the underlying sequence. These tags can be added or removed in response to developmental cues or environmental stress, and in cancer they are often hijacked to silence protective pathways or lock cells into a proliferative state.

In childhood brain tumors, for example, researchers have shown that DNA methylation alterations are associated with cancer, and that subtle variation in these patterns can shape how aggressive a tumor becomes and how it responds to therapy. The same logic applies across malignancies: once chromosomal instability has disrupted the genome, epigenetic machinery can either attempt to restore order or, more ominously, stabilize a malignant program that helps the tumor thrive. When I connect the dots from chromosomal damage to these chemical marks, the idea that Known epigenetic mechanisms and DNA methylation alterations might be directly sculpted by chromosomal instability feels less like a surprise and more like a missing piece finally snapping into place.

From single cells to neighborhoods: mapping hallmarks in space

One reason this link stayed hidden for so long is that most studies treated tumors as uniform blobs, averaging signals across millions of cells. New spatial technologies are changing that, revealing that cancer hallmarks are not evenly distributed but instead form distinct neighborhoods within a tumor. A recent Schema showing the median spatial location of cells highly active in each hallmark illustrates how different regions specialize in proliferation, immune evasion, or invasion, creating a patchwork of microenvironments that cooperate to sustain the disease.

By layering chromosomal and epigenetic data onto these spatial maps, researchers can now see where instability and regulatory rewiring cluster, and how they correlate with other hallmarks like angiogenesis or inflammation. Tumors are complex ecosystems of interacting cell types, and spatial transcriptomics has made it clear that cancer hallmarks emerge from the interplay between malignant cells and their microenvironment rather than from any single mutation. When I look at these spatial patterns, the idea that chromosomal instability and epigenetic change are linked is reinforced by the way they co-localize in regions that drive growth and resistance, as shown in detailed analyses of Tumors as complex ecosystems and in the accompanying Schema of hallmark activity.

Shapeshifting carcinomas and the hidden switches of identity

The chromosomal–epigenetic link also helps explain one of the most troubling behaviors in oncology: the ability of some carcinomas to change identity when threatened. Scientists are uncovering what makes certain tumors so resistant to targeted drugs, and a key factor is their capacity to switch lineage, adopting features of a different cell type that no longer depends on the original drug target. This plasticity is not random; it is orchestrated by regulatory networks that respond to stress signals, including those triggered by genomic instability.

Two new studies have pinpointed hidden switches that let tumors shapeshift and evade treatment, implicating both transcription factors and chromatin modifiers that sit at the intersection of genetic damage and epigenetic control. When chromosomal instability disrupts key regions, it can activate these switches, prompting a wholesale reprogramming of cell identity that leaves therapies chasing a moving target. For me, the fact that Scientists and Two complementary studies tie this plasticity to specific molecular levers suggests that targeting the epigenetic consequences of chromosomal instability could be just as important as blocking the initial mutations.

Uveal melanoma and the “emerging” hallmarks that fill in the gaps

Some cancers make the chromosomal–epigenetic interplay especially visible because they are driven by a relatively small set of recurrent alterations. Uveal melanoma is one of those, and it has become a proving ground for how the classic hallmarks framework is evolving. An increasing body of research suggests that two “emerging” hallmarks of cancer and two “enabling characteristics” are involved in uveal melanoma, adding layers like immune modulation and metabolic reprogramming to the traditional list of capabilities.

These emerging hallmarks and enabling traits are tightly connected to both genetic lesions and epigenetic states, which together determine whether a uveal melanoma remains localized or progresses to lethal metastatic disease. When I consider how chromosomal instability might feed into these processes, it is easy to see how structural changes could set the stage for epigenetic programs that support immune escape or altered metabolism. The detailed discussion of these capabilities, and their relationship to UM, in the context of An increasing body of research on emerging hallmarks underscores how incomplete any model of cancer would be if it ignored the crosstalk between chromosomal architecture and epigenetic control.

Revisiting the genetic basis of cancer in light of epigenetic feedback

The classic view of cancer as a genetic disease still holds, but it now looks more like the foundation of a multi-layered structure than the whole building. Early work on the genetic basis of cancer emphasized how mutations and chromosomal rearrangements disrupt normal growth controls, and how these changes accumulate over time. Cancer cells have both numerical and structural abnormalities of chromosomes, and this genomic disarray was long seen as the primary engine of malignancy, with other hallmarks treated as downstream consequences.

What the new chromosomal–epigenetic link adds is a sense that the genome is not just a static blueprint that gets damaged, but a dynamic platform whose physical state shapes and is shaped by regulatory marks. When chromosomes break or mis-segregate, they do not simply alter gene dosage; they also create new contexts for epigenetic enzymes to act, which can lock in malignant programs or open up new evolutionary paths. Revisiting the story that began with the German biologist who first tied chromosomes to heredity, I now see the modern synthesis of Cancer genetics and the German chromosomal insight as incomplete without acknowledging how epigenetic feedback loops amplify the impact of each structural lesion.

Therapeutic implications: targeting the loop, not just the nodes

All of this has practical consequences for how I think about treating cancer. If chromosomal instability and epigenetic change are part of a single loop, then therapies that hit only one side may offer temporary relief while the other side compensates. Drugs that stabilize chromosomes without addressing the epigenetic programs they have already set in motion might slow the generation of new variants but leave entrenched malignant states intact. Conversely, epigenetic drugs that reset DNA methylation or chromatin structure could be undermined if ongoing chromosomal instability keeps reintroducing disruptive lesions.

The more promising strategy is to look for combination approaches that interrupt the feedback itself, for example by pairing agents that reduce chromosomal mis-segregation with those that block the epigenetic machinery tumors use to adapt. Spatial mapping of hallmarks can guide where and when to deploy such combinations, focusing on regions where instability, epigenetic reprogramming, and other hallmarks like immune evasion converge. As researchers refine these maps and dissect the molecular switches identified by lineage plasticity studies, the once abstract idea of “linking hallmarks” is starting to look like a concrete roadmap for designing safer, more selective cancer drugs that exploit the very connections tumors depend on.

More from MorningOverview