Just off a quiet Aegean shoreline, scientists have stumbled onto a seafloor landscape that looks less like a Mediterranean holiday postcard and more like a scene from another world. A newly mapped hydrothermal field near the Greek island of Milos is so extensive and so active that researchers say they were “stunned” by its scale, its heat and the way it rewrites what they thought they knew about this corner of the Earth’s crust.

The discovery reveals a boiling, mineral-rich world hidden only a short distance from popular beaches, where superheated fluids rise along deep fault zones and burst through the seabed in shimmering plumes. It is a reminder that beneath the surface of familiar places, the planet is still cracking open, still venting its interior, and still offering clues to how oceans, life and even other worlds might work.

How scientists found a “boiling world” off Milos

The starting point for this story is geography. Milos sits in the southern Aegean volcanic arc, a chain of islands shaped by the slow collision of tectonic plates beneath Greece, where magma, faulting and hot fluids have long been part of the landscape. Scientists already knew Milos for its hot springs and shallow-water vents, but when they began a new, high resolution survey of the seafloor, they expected to refine that picture, not to find an entirely new hydrothermal province hiding in plain sight.

Instead, as Dec expeditions mapped the seabed and sampled the water column, Scientists realized they were looking at a vast hydrothermal field stretching along active fault lines, with venting that extended far beyond previously known sites. The work, described in a study in Scientific Reports and summarized in several technical briefings, shows that the vents are aligned with deep crustal structures where Fault Zones Shape Where Vents Appear, guiding hot fluids up from depth until they emerge at the seabed in a dense cluster of chimneys and diffuse flows that had never been charted before.

A giant hydrothermal field hiding in the Mediterranean

What makes this discovery so striking is not just that there are vents off Milos, but how many there are and how closely packed they seem to be. According to Dec reporting that highlighted how Scientists were stunned by a massive hydrothermal field off Greece, the team identified an extensive underwater vent system that rivals some of the better known fields on mid ocean ridges, yet sits in a semi enclosed basin that most people associate with warm, relatively quiet waters rather than deep ocean style volcanism. The field’s footprint, as reconstructed from sonar and visual surveys, suggests a continuous hydrothermal system rather than a scattering of isolated springs.

Researchers emphasize that this is not a single towering “black smoker” complex, but a mosaic of structures, from low temperature seeps to high temperature jets, all feeding off the same tectonic engine. In one summary, Scientists described how the vents are concentrated along a corridor of active faults that cut the seafloor near Milos, with the most intense activity clustered at what they call the White Sealhound structure, a feature that appears to focus fluid flow and mineral deposition. That pattern, documented in detail in a Dec release on how Fault Zones Shape Where Vents Appear, is what justifies calling this a massive hydrothermal field rather than a handful of scattered anomalies.

The “boiling world” beneath the waves

For anyone swimming off Milos, the idea that there is a boiling world just offshore sounds like hyperbole, but the temperature measurements tell a different story. As Scientists pushed instruments into the seafloor and sampled rising plumes, they recorded fluids hot enough to flash water into shimmering curtains, creating the visual impression of underwater “boil” even where the surrounding sea stayed relatively cool. One detailed account described how Scientists recently stumbled upon something incredible just off the coast of the Greek island of Milos, where the seafloor is punctured by vents that discharge superheated water and gases into the overlying Aegean.

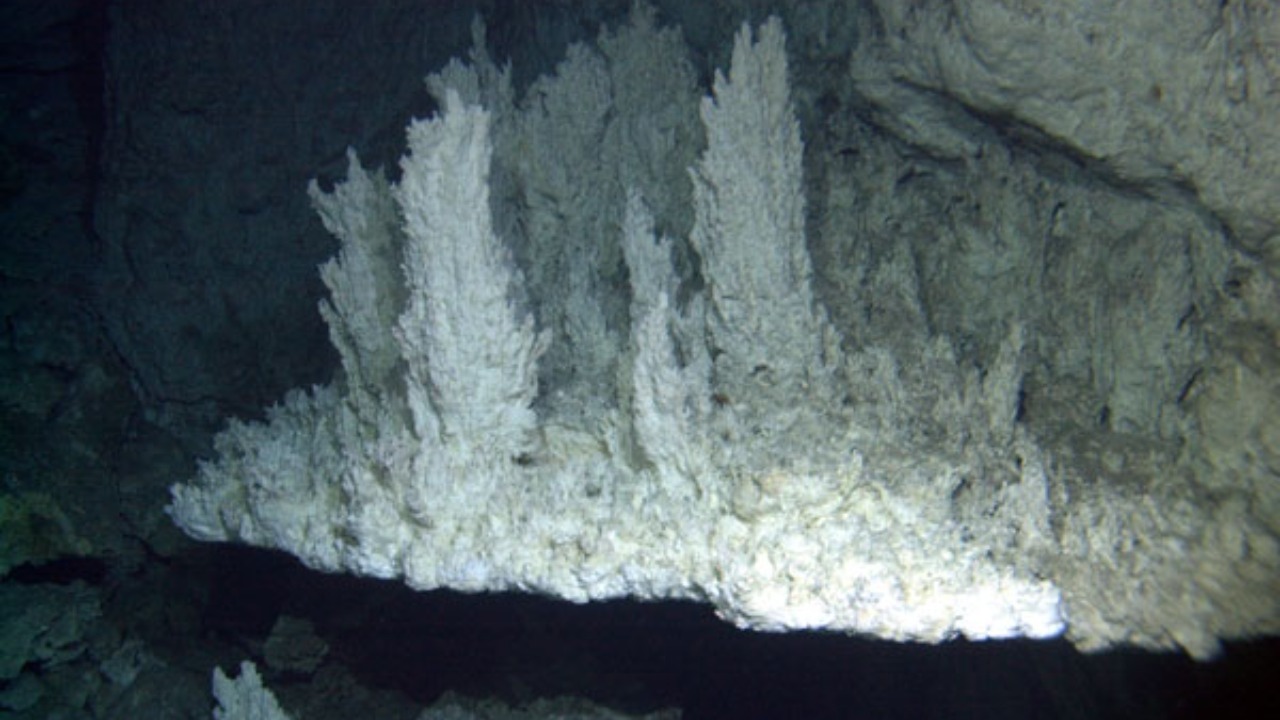

Those same reports describe the area as a kind of natural laboratory, where the combination of heat, minerals and steep chemical gradients creates conditions that are harsh for most familiar marine life but ideal for specialized microbes. The phrase “boiling world under the Greek sea” is not just a metaphor, it reflects direct observations of vigorous venting, bubbling gas and milky plumes that transform patches of seabed into alien looking terrain. While exploring this environment, Scientists noted that some of the vent fields, with their icy looking mineral crusts and dark fractures, resemble conceptual images of the ocean floor on Jupiter’s moon Europa, a comparison that underscores just how unusual this Mediterranean setting really is.

Fault zones as the hidden architects

At the heart of the new research is a simple but powerful idea, that the architecture of the crust controls where hydrothermal vents can exist. In the Milos field, Scientists traced the vents back to a network of active faults that slice through the upper crust and act as conduits for hot fluids rising from deeper magmatic or metamorphic sources. A Dec synthesis titled Fault Zones Shape Where Vents Appear explains how these fractures localize both the heat and the permeability, so that instead of diffuse warming, the system produces focused jets of superheated water that erupt at the seabed in narrow bands.

That structural control helps explain why such a large hydrothermal system could remain hidden until now. The vents are not spread evenly across the seafloor, they are tucked into fault bounded depressions and along subtle scarps that standard, low resolution surveys can easily miss. Only when Researchers combined detailed bathymetry, targeted sampling and geophysical imaging did the full pattern emerge, revealing a corridor of venting that tracks the underlying faults almost like a tracer dye. This insight, laid out in the Dec analysis of how Fault Zones Shape Where Vents Appear, suggests that similar, undiscovered fields may exist wherever comparable fault systems cut through volcanic arcs or back arc basins.

A Mediterranean system that looks like another planet

One of the most striking aspects of the Milos discovery is how often Scientists reach for planetary analogies to describe it. In their field notes and public briefings, they compare the boiling, mineral rich seafloor to the hypothesized oceans beneath the ice shells of outer solar system moons. A Dec feature framed the find as part of a broader realization that the Mediterranean seafloor is cracking open, revealing hidden pathways where hot fluids circulate through the crust and vent into the ocean, a process that could mirror what happens on icy worlds where tidal forces, rather than plate tectonics, drive fracturing.

That planetary echo is not just poetic language, it is grounded in specific observations of how the vents alter the seabed. In one widely shared visual summary, Scientists described new evidence that the Earth is cracking open, with fractures that channel hot, chemically reactive fluids in ways that resemble models for hydrothermal circulation on other planets and moons. The post, shared under the handle originalsaibu, highlighted how these Mediterranean vents, captured in the originalsaibu feed, could serve as real world test beds for understanding environments that might exist on Europa or Enceladus, where similar chemistry could support microbial ecosystems in the absence of sunlight.

Why Milos is a natural laboratory for life’s extremes

From an astrobiology perspective, the newly mapped field off Milos is a gift. Hydrothermal systems are already central to debates about how life began on Earth, and the combination of heat, minerals and steep chemical gradients in this Aegean setting offers a compact, accessible version of those conditions. A Dec overview of newly discovered hydrothermal fields off the island of Milos notes that Bühring, senior author of the study and scientist at the MARUM – Center for Marine Environmental Sciences, University of Bremen, sees the site as a key place to study the interplay between tectonics, volcanism and hydrothermal activity, all of which shape the energy landscape available to microbes.

In that same work, the team emphasizes that the Milos vents host microbial communities adapted to high temperatures, low oxygen and high concentrations of dissolved metals and gases, conditions that mirror some of the scenarios proposed for early Earth. The fact that these communities thrive in a semi enclosed basin, close to shore and within reach of standard research vessels, makes them especially valuable. As the Dec astrobiology summary on newly discovered hydrothermal fields off the island of Milos explains, the combination of MARUM led geochemical measurements and biological sampling is already yielding insights into how life exploits the sharp gradients created where hot, reduced fluids mix with cooler, oxygenated seawater.

How can boiling springs sit so close to a beach?

For local residents and visitors, one of the most disorienting aspects of the discovery is its proximity to familiar coastlines. The vents are not tucked away in the deep abyss, they are located near the shores of a Mediterranean island better known for whitewashed villages and calm bays. A Dec explainer framed the central puzzle bluntly, How can boiling water springs emerge so close to the shores of a Mediterranean island, and what does that say about the underlying geology. The answer, it argues, lies in the unique combination of thin crust, active faulting and residual magmatic heat beneath Milos, which together create a narrow but intense corridor of hydrothermal circulation.

That same analysis describes the system as a major hydrothermal system discovered in the Mediterranean, notable both for its scale and its location. The vents, some of which discharge near the seabed in water shallow enough for snorkelers to see shimmering plumes, are fed by fluids that have traveled along deep faults and been heated far below the surface. As the Dec piece on a major hydrothermal system discovered in the Mediterranean explains, the contrast between the tranquil surface and the energetic subsurface is precisely what makes Milos such a compelling case study, a place where the forces that usually operate in remote mid ocean settings are compressed into a coastal environment.

Mapping a hidden giant off Milos Island

To appreciate the scale of what has been found, it helps to zoom out and look at Milos in its regional context. The island, cataloged in global knowledge graphs as Milos Island, sits near the junction of several tectonic blocks, where the African plate is being forced beneath the Eurasian margin. That setting has produced a long history of volcanism, from explosive eruptions that built the island’s tuff cliffs to quieter phases that left behind geothermal reservoirs tapped today for energy and tourism. The newly documented hydrothermal field adds a submarine chapter to that story, one that had been largely speculative until detailed mapping campaigns filled in the gaps.

According to Dec summaries that focus on how Scientists have uncovered an extensive underwater vent system near Milos, Greece, the field stretches along active fault lines beneath the Aegean, with the densest venting concentrated at the White Sealhound structure. In that account, Scientists describe how they used a combination of sonar, submersible observations and geochemical tracers to delineate the boundaries of the system, revealing a patchwork of chimneys, mounds and diffuse flow zones that together form one of the largest known hydrothermal complexes in the region. The same report, which highlights how Scientists were stunned by a massive hydrothermal field off Greece, underscores that this is not an isolated curiosity but a major feature of the local seafloor, one that will need to be factored into future geological and hazard assessments.

From Scientific Reports to tsunami risk

The scientific backbone of the Milos discovery is a peer reviewed study that appears in Scientific Reports, where Dec authors lay out the evidence for a surprisingly large hydrothermal vent field along the underwater slopes near the island. In that paper, the team details how they combined structural geology, fluid chemistry and heat flow measurements to show that the vents are not random, but systematically aligned with faults that cut through the crust and emerge at the seabed. A Dec synthesis of the work notes that the study in Scientific Reports describes the discovery of a surprisingly large hydrothermal vent field along the underwater slopes of Milos, and that the authors interpret this as a sign of ongoing tectonic and magmatic activity beneath the Aegean.

Those same findings have caught the attention of researchers who study natural hazards, particularly tsunamis. While hydrothermal venting itself does not generate large waves, it is often associated with faulting and volcanism that can. A Dec roundup of Top Headlines on tsunamis, which includes an item titled Scientists Stunned by a Massive Hydrothermal Field Off Greece, highlights how the discovery feeds into broader questions about how active the seafloor really is in this part of the Mediterranean. In that context, Scientists are careful to distinguish between the immediate spectacle of boiling vents and the longer term need to monitor the faults that feed them, since those structures, if they slip or host submarine landslides, could contribute to tsunami generation in the wider region.

Why this Mediterranean field matters far beyond Greece

For all its local drama, the Milos hydrothermal field is ultimately a global story about how Earth works. It shows that even in relatively well studied basins like the Mediterranean, large and energetically significant hydrothermal systems can remain undetected until the right combination of tools and questions is brought to bear. The Dec coverage that first described how Scientists were stunned by a massive hydrothermal field off Greece makes clear that this is not just a curiosity for geologists, it is a reminder that the planet’s plumbing is more complex and more dynamic than surface maps suggest, with implications for everything from mineral resources to carbon cycling.

It also reinforces the idea that coastal volcanic arcs can host hydrothermal systems that bridge the gap between deep ocean vents and shallow, land based hot springs. In the case of Milos, that bridge runs through a field of vents that sit within the territorial waters of Greece, close enough to shore that their plumes mingle with coastal currents and their chemistry can influence nearby ecosystems. As Dec reports on Scientists recently stumbling upon something incredible just off the coast of the Greek island of Milos put it, the discovery of this boiling world under the Greek sea is not just a spectacular find, it is a new reference point for how scientists think about the links between tectonics, hydrothermal activity and life, both on this planet and, potentially, on others.

More from MorningOverview