Hints of ancient microbes in Martian rocks and a revived theory about our cosmic ancestry are forcing scientists to rethink where the story of life really began. Instead of a warm little pond on early Earth, some researchers now argue that biology may have first sparked on Mars, then rode meteorites to the planet we call home. The idea is still controversial, but a new wave of data and debate is pushing it from the fringes of speculation into the center of origin-of-life research.

Why Mars is suddenly back at the origin-of-life table

For decades, the question of how life began has focused on Earth, with competing scenarios involving deep-sea vents, volcanic pools, or icy chemistry. I now see that conversation shifting, because early Mars appears to have ticked many of the same boxes that made our own planet habitable, including liquid water, volcanic activity, and long-lived lakes and rivers. Astrobiologists studying Life on Mars note that the planet once had a thicker atmosphere and a milder climate, conditions that could have supported microbial ecosystems even if the surface is hostile today.

That backdrop matters because the more Mars looks like a younger sibling of Earth, the more plausible it becomes that biology might have started there first. A recent study highlighted in late Dec revisits the idea that life may have originated on Mars before Earth, arguing that the Red Planet’s early environment could have been more stable for fragile prebiotic chemistry. In that framing, Earth is not the cradle of life but the beneficiary of a cosmic transfer, with our biosphere seeded by hardy microbes that first evolved on another world.

The Cheyava Falls rocks that reignited the Mars life debate

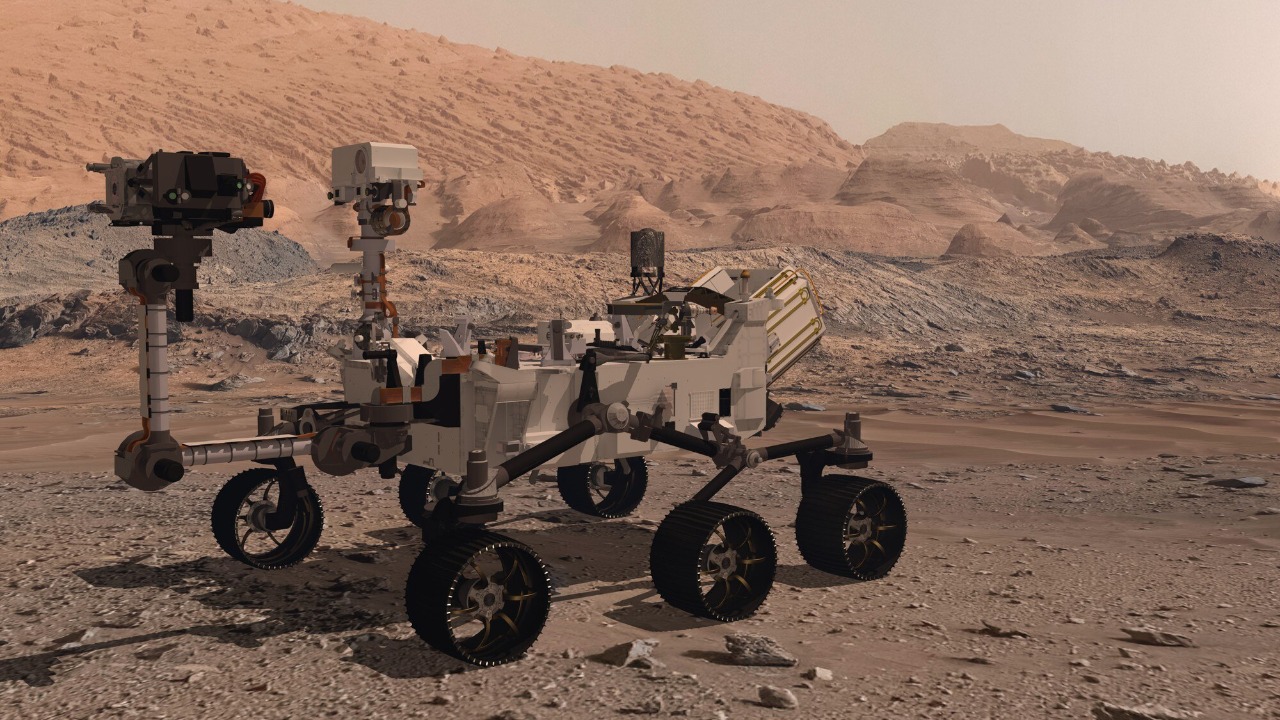

The abstract question of Martian origins has taken on new urgency because of a specific set of rocks in Jezero Crater. NASA’s Perseverance rover, exploring an ancient river delta, found a reddish boulder nicknamed Cheyava Falls that is mottled with dark, circular patches scientists call leopard spots. According to NASA, Perseverance spotted leopard spots and greenish “poppy seeds” on this rock in Mars’ Jezero Crater, features that appear enriched in certain elements in a way that hints at chemical processes once powered by microbes.

Researchers spent roughly a year testing non-biological explanations, from mineral growth to radiation damage, and still could not easily explain what they saw. A detailed analysis described by Oct in a deep dive on Our best proof of life on Mars yet notes that the patterns in Cheyava Falls resemble textures on Earth that form when microbial mats alter rock chemistry over long periods. The team is careful to call this a “potential biosignature,” not proof of Martians, but the discovery has raised the stakes for the entire Mars program, because samples from this rock could eventually be returned to Earth for definitive tests.

From “Martians” to microbes: how the idea evolved

Popular culture has long imagined Mars as a world of canals and intelligent Martians, a vision that still shapes how people react when scientists talk about life there. Modern researchers are focused on something far more modest and, in many ways, more radical: the possibility that simple microbes once thrived in Martian lakes and sediments. A widely viewed documentary segment on Mars and Martians underscores that scientists now suspect the barren world we see today may once have swarmed with microscopic organisms, not the humanoid aliens of science fiction.

That shift from fantasy to geochemistry has changed the tone of the debate. Instead of asking whether there are cities on Mars, researchers are asking whether subtle mineral textures, isotopic ratios, or organic molecules in rocks like Cheyava Falls can only be explained by biology. The long-running catalog of possible Martian life signs includes methane plumes, recurring slope lineae, and carbonate globules in the Martian meteorite ALH84001, all of which sparked intense debate but ultimately fell short of consensus. The new evidence from Jezero Crater is being judged against that history, with scientists determined not to repeat earlier overstatements.

What Perseverance is really telling us about ancient Mars

Perseverance’s findings are not just about one photogenic rock, they are about reconstructing an entire vanished ecosystem. NASA’s own summary of the mission’s progress notes that the rover has drilled into fine-grained sediments in the “Sapphire Can” area and identified minerals that typically form in long-standing water. In a special report, NASA highlighted that Says Mars Rover Discovered Potential Biosignatures after a year of scrutiny, with textures and chemical signatures that are consistent with ancient microbial life processes, even if they are not yet conclusive.

Independent coverage has echoed that cautious excitement. One detailed account described how the “leopard-spot” rocks could be the most compelling signs of life ever found on another world, quoting scientists who say the patterns are hard to reproduce without biology. The report on Life on Mars leopard spots notes that the features are enriched in elements like iron and manganese in ways that, on Earth, often trace back to microbial activity. Another analysis of the same dataset, framed as a Study of Signs of life, stresses that the textures could still have non-biological origins, but that the combination of mineralogy, context, and patterning makes them the strongest candidates yet for a Martian biosignature.

Why some chemists think Mars had the better starting kit

Even before Perseverance, some origin-of-life researchers argued that Mars might have offered a more favorable chemical environment for life’s first steps. One influential line of reasoning focuses on how certain minerals and elements behave under different planetary conditions. Reporting on early work in this area explained that Life on Mars might have benefited from more accessible oxidized minerals on the Martian surface, which could catalyze the formation of complex organic molecules on the crystalline surfaces of minerals in ways that were harder to achieve on early Earth.

More recently, Japanese scientists modeled how microbial spores or prebiotic chemistry could survive in rocks blasted off Mars and traveling through space. Their work, summarized in a report that opens with the blunt statement that How life arose on Earth remains a mystery, suggests that microbes shielded inside meter-scale rocks could survive for up to 10 years in space, long enough to make the journey from Mars to Earth. That finding undercuts one of the main objections to Mars-first scenarios, which is that the trip through vacuum and radiation would sterilize any hitchhiking organisms.

Panspermia, from “wild” idea to testable hypothesis

The notion that life can travel between worlds is known as panspermia, and it has a long history of being dismissed as fringe. Early proponents suggested that asteroids and comets could act as incubators for microbes, carrying them across interplanetary or even interstellar distances. A recent overview notes that these once Wild theories are now being revisited as laboratory experiments show that some bacteria and spores can survive extreme cold, vacuum, and radiation for surprisingly long periods, especially when shielded by rock or ice.

Modern panspermia research is less about aliens seeding planets on purpose and more about physics and probability. A detailed explainer on Panspermia and Earth describes how impacts can eject debris into space, some of which eventually intersects the orbits of other planets. Another analysis traces how the reemergence of this theory is intertwined with the slow progress in pinning down a purely Earth-based origin, arguing that it is no longer enough to say “life started here” without explaining why our planet, and not Mars, had the winning combination of chemistry and stability. As one long-form piece on Mars origin of life points out, panspermia does not solve the mystery of how life began, it simply relocates the first spark to another world and asks whether that world might have been Mars.

Could Martian rocks really seed Earth with life?

The mechanics of getting life from Mars to Earth are surprisingly well understood. When a large asteroid slams into Mars, it can blast chunks of crust into space at escape velocity, some of which eventually cross Earth’s orbit and fall as meteorites. Astronomers studying this process have calculated that a significant number of Martian rocks have landed here over the planet’s history, and that some of them would have spent relatively short times in transit. A detailed breakdown of this scenario explains that if pieces from Mars were knocked off via ballistic panspermia, they could land in the right puddle on Earth with microbes still dormant but viable inside.

Laboratory experiments and computer models now suggest that microbes embedded several centimeters deep in rock could survive the shock of ejection, the cold of space, and the heat of atmospheric entry. A recent synthesis of new data on origin-of-life timing argues that it is “entirely plausible” that life arose on the Red Planet first and then survived the trip to Earth. In that analysis, the authors emphasize that But Mars could have cooled and stabilized earlier than Earth, giving it a head start of tens of millions of years. If that is true, then the first terrestrial microbes might literally be Martian immigrants that adapted to a new world.

How new studies are reframing the “where” of life’s origin

What is changing now is not just the data from Mars, but the way origin-of-life scientists frame their questions. Instead of treating Earth as the default starting point, some researchers are building models that compare multiple worlds, asking which had the right combination of water, energy, and chemistry at the right time. A recent study, highlighted in Dec, explicitly revisits the idea that life may have originated on Mars, not Earth, and argues that the probability of life emerging on our own planet might be lower than previously assumed if key minerals or environmental cycles were missing.

At the same time, some scientists are broadening the conversation beyond Mars entirely, asking whether life on Earth could have been seeded by comets, asteroids, or even interstellar dust. A recent feature on whether humans were seeded by aliens notes that the idea of life beginning elsewhere in space is gaining traction as more exoplanets are discovered and as we learn how resilient microbes can be. That does not mean most researchers think intelligent aliens deliberately sent life here, but it does mean that the origin story is no longer confined to one planet or one narrow set of conditions.

Why none of this is proof, and why it still matters

For all the excitement around Cheyava Falls and Martian panspermia, there is still no smoking gun that proves life began on Mars. The textures in Jezero Crater rocks could yet turn out to be exotic mineral growths, and the chemistry that favors life’s emergence might have been just as accessible on early Earth. A careful analysis of the rover data notes that the “most compelling” features are still ambiguous, and that scientists have pointed out non-biological processes that could produce some of the same patterns. One widely shared account of the rover’s work describes how the rocks were speckled with greenish dots dubbed poppy seeds and leopard spots, enriched with certain elements, but stresses that In addition to biological explanations, there are still plausible abiotic reactions that might account for these minerals.

That uncertainty is why NASA and its partners are investing heavily in Mars Sample Return, which aims to bring carefully selected rocks, including material from Cheyava Falls, back to Earth for analysis with the full arsenal of modern laboratories. Coverage of the initial announcement about the potential biosignature framed the discovery with a simple question, asking whether Has NASA finally found evidence that life once existed on Mars, then answering with a cautious “not yet.” Even so, the revived theory that life may have started on Mars is already reshaping mission priorities, laboratory experiments, and philosophical debates about what it means to be “from” a particular planet.

What a Martian origin would mean for us

If future analysis confirms that life began on Mars and later colonized Earth, the implications would be profound but also strangely grounding. On one level, it would mean that every plant, animal, and person on this planet is part of a lineage that started on another world, making us literal Martians by ancestry. A long-running discussion of Our Mars meteorite evidence, including the famous ALH84001 rock, has already accustomed scientists to the idea that planetary boundaries are porous, with material and perhaps microbes moving between worlds over time.

On another level, a Martian origin would make life feel more universal, not less. If biology can start on Mars, survive ejection into space, and take root on Earth, then the universe may be far more fertile than we imagined. A recent synthesis of origin-of-life research argues that the reemergence of panspermia as a serious idea reflects both our growing catalog of habitable environments and our frustration with pinning down a single birthplace. As one overview of Mars origin debates notes, the real breakthrough may not be proving that life started on one planet or another, but recognizing that in a dynamic solar system, the story of life is written across multiple worlds, with Mars and Earth as just two chapters in a much longer cosmic narrative.

More from MorningOverview