Humanoid robots are starting to gain something that once belonged firmly in the realm of science fiction: a sense of pain. Chinese researchers have built a neuromorphic electronic skin that lets machines detect harmful contact, recognize damage and trigger lightning fast reflexes, bringing industrial and service robots closer to the way human bodies protect themselves. The technology promises safer collaboration between people and machines, but it also raises fresh questions about how far we really want robots to feel.

At the heart of this advance is a new class of flexible “robot skin” that fuses tactile sensing with brain inspired computing so that signals are processed directly on the surface instead of being shipped off to a distant processor. That design lets humanoids react in milliseconds when they are squeezed, cut or burned, rather than waiting for a central controller to decide what to do. I see this as a pivotal shift in robotics, one that could redefine how we design factories, hospitals and even home assistants in the decade ahead.

From touch to pain: what neuromorphic e-skin actually is

The Chinese team’s work centers on a neuromorphic robotic electronic skin, often shortened to NRE skin, that treats every sensing node a bit like a biological neuron. Instead of simply measuring pressure or temperature and sending raw numbers to a computer, each tiny unit in the network converts physical stimuli into electrical spikes that resemble the way nerves fire in a human arm. That spike based approach is what lets the material distinguish between a gentle touch and a potentially damaging blow, and it is the foundation for the “pain” response that gives the technology its headline grabbing edge.

In technical terms, the researchers describe the system as a Here, NRE system that not only senses basic contact but also encodes the intensity and type of stimulus in a way that can be processed locally. By embedding this neuromorphic architecture directly into the skin, they avoid the bottleneck of streaming huge volumes of sensor data to a central processor, which is one reason traditional robots often react slowly or clumsily to unexpected contact. The result is a surface that behaves less like a sheet of electronics and more like a living sensory organ.

China’s prototype that lets humanoids flinch

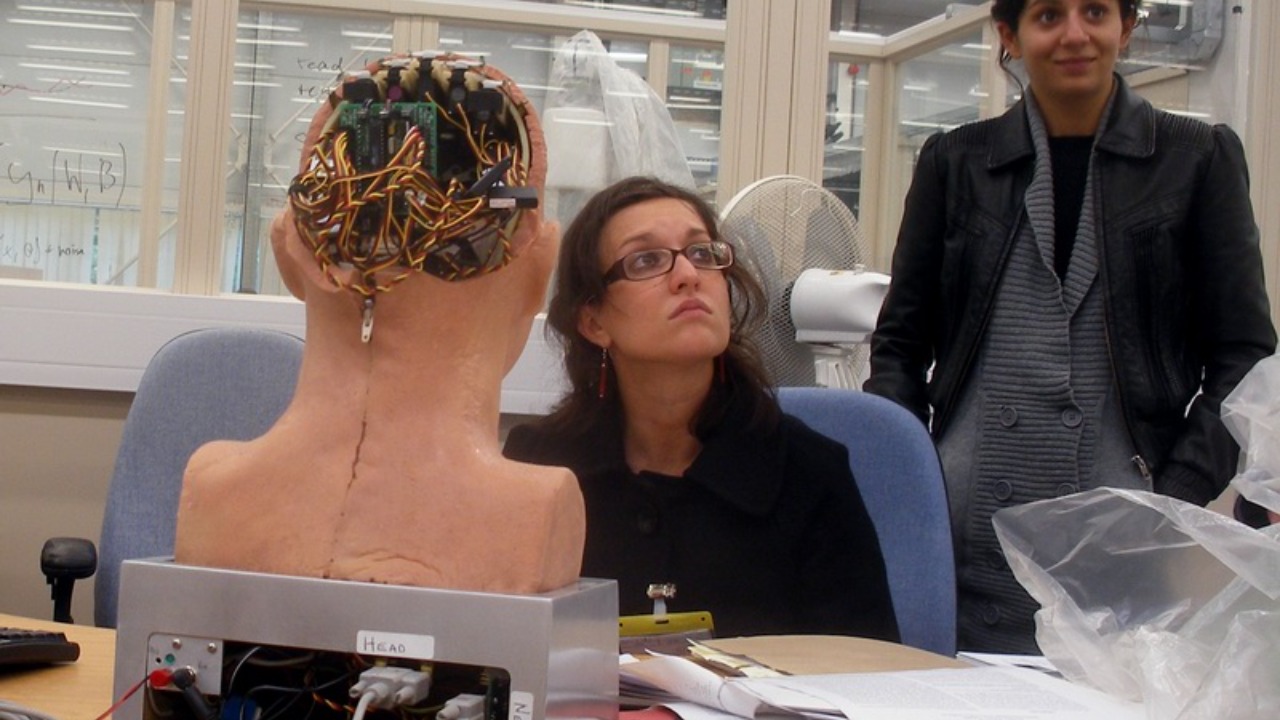

What makes the Chinese project stand out is not just the theory but the working prototype that has already been wrapped around humanoid style robots. The team built a layered patch of NRE skin and attached it to robotic limbs so that the machine could detect when its surface was cut, pressed or otherwise damaged, then respond with a reflexive movement. Instead of waiting for a high level control loop, the limb itself “decides” to pull away, much as a person instinctively withdraws a hand from a hot stove before consciously registering the burn.

According to reporting on the project, a new neuromorphic robotic skin from China enables humanoid robots to sense pain, detect injury and trigger rapid reflex responses that are tuned to the severity of the threat. Separate coverage notes that Researchers have developed a prototype of neuromorphic artificial skin specifically to prevent robots from accidentally crushing people, highlighting the safety motivation behind the work. By combining injury detection with graded reflexes, the prototype moves beyond simple bump sensors and into a realm where robots can modulate their behavior based on how dangerous a contact appears to be.

How the “pain” circuit works at machine speed

For a robot, feeling pain is less about emotion and more about thresholds and timing. The NRE skin uses its neuromorphic circuitry to encode different levels of force, heat or other stimuli into distinct spike patterns, then compares those patterns to built in limits that represent safe and unsafe conditions. When a reading crosses a critical threshold, the local circuit triggers a reflex command that can override slower, higher level instructions, ensuring that the robot backs off or relaxes its grip before damage occurs. This is the same logic that keeps a human from holding onto a sharp object even if they are focused on another task.

The Chinese work builds on a broader wave of research into neuromorphic tactile systems, where Researchers explicitly model their circuits on the layered structure of human skin and the way pain fibers fire under stress. In the NRE skin, those layers are implemented in flexible electronics that can be stretched and bent with a robot’s joints, so the reflex pathways stay intact even as the machine moves. Because the computation happens at the level of the neuromorphic architecture, the system can scale to large surfaces without overwhelming a central processor, which is crucial if full body humanoids are ever going to be covered in responsive skin.

Global race to give robots a sense of touch

China’s neuromorphic e-skin does not exist in isolation. Around the world, labs are racing to give robots richer tactile abilities, from simple pressure sensing to full temperature and pain perception. Earlier this year, a separate team reported a flexible robotic skin that can detect heat, pain and pressure across a dense network of sensing pathways, pointing to a convergence between different national efforts. I see this as an emerging global standard: if robots are going to work shoulder to shoulder with people, they will need something much closer to human like touch.

In one influential project, Researchers created a revolutionary robotic skin made from a flexible material that integrates sensing and processing, echoing the neuromorphic approach seen in the Chinese NRE design. The same line of work notes that the skin can pick up signals from over 860,000 tiny pathways embedded into soft, flexible materials, a figure that hints at how dense and information rich future robot skins may become. Although the robotic skin in that study is not as sensitive as human skin, its scale and flexibility show how quickly the field is moving toward full body coverage.

Why pain sensing matters for safety around people

The most immediate impact of pain capable robot skin is safety. Industrial arms and humanoid helpers are increasingly sharing space with human workers, whether in automotive plants, logistics centers or hospital corridors. Without a fine grained sense of contact, these machines rely on crude safeguards like light curtains, emergency stop buttons or conservative speed limits, which either leave gaps in protection or slow operations to a crawl. A robot that can feel when it is squeezing too hard, or when its surface has been cut or overheated, can react in a more nuanced way that protects people without shutting everything down.

The Chinese NRE skin is explicitly framed as a way to prevent accidents, with prototype systems designed so that a robot loosens its grip before it crushes a hand or fragile object. The ability to detect injury on the robot’s own body also matters, since a damaged joint or torn cable can pose hidden risks if the machine keeps operating at full power. By giving robots a built in incentive to protect their own “skin,” engineers are effectively aligning machine behavior with human safety, a subtle but important shift in how we think about collaborative automation.

Inside the materials: flexible skins that wrap real robots

Under the microscope, these new skins are a blend of soft polymers, conductive traces and neuromorphic circuits that can stretch and flex with a robot’s movements. The Chinese NRE design uses a layered structure that mimics the epidermis and dermis, with sensing elements near the surface and processing elements deeper inside. That architecture lets the skin conform to curved surfaces like humanoid arms or torsos while still routing signals efficiently to local processing hubs. It is a far cry from the rigid metal shells that defined earlier generations of industrial robots.

Parallel work on tactile skins has shown how far this materials science has come. In the project where Made from a flexible base, the robotic skin integrates sensing nodes and wiring into a continuous sheet that can be draped over complex shapes. Jun and other collaborators emphasize that, although the robotic skin is not as sensitive as human skin, it can still detect signals from over Although the tiny pathways embedded into soft, flexible materials, which is enough to support detailed maps of contact and pressure. The Chinese NRE skin taps into the same toolkit of stretchable conductors and elastomers, but adds neuromorphic processing so that the material is not just a sensor array but a distributed computer.

From lab demo to factory floor and hospital ward

Turning a lab prototype into a workhorse technology is never straightforward, and pain sensing robot skin is no exception. To be useful in a car plant or a warehouse, the NRE patches will need to survive oil, dust, repeated impacts and constant flexing, all while maintaining their delicate neuromorphic circuits. They will also have to integrate with existing robot controllers from companies like Fanuc, ABB or Boston Dynamics, which means translating spike based signals into commands that legacy systems can understand. I expect early deployments to focus on high risk contact zones, such as grippers and elbows, before full body coverage becomes practical.

Healthcare is another likely early adopter. Humanoid assistants that help lift patients, deliver supplies or support rehabilitation exercises need a refined sense of touch to avoid bruising fragile skin or aggravating injuries. A Chinese style NRE skin that can detect pain level contact and adjust force in real time could make robots more trustworthy in nursing homes or rehabilitation centers, where human staff are already stretched thin. As robots increasingly operate around people, the ability to sense and respond to harmful contact will likely become a regulatory expectation rather than a futuristic bonus feature.

Ethical lines: when “pain” stops being just a metaphor

For now, the pain in neuromorphic e-skin is a functional metaphor, a way to describe threshold based reflexes that protect hardware and humans. The circuits do not feel in any conscious sense, and there is no evidence in the sources that the Chinese NRE system has anything like subjective experience. Still, as engineers borrow more language from biology and build ever richer sensory systems, the line between metaphor and moral concern can start to blur in the public imagination. I have already seen debates about whether it is acceptable to deliberately damage a robot that reacts as if it is hurt, even when we know it is just executing code.

Those questions will only intensify as neuromorphic architectures grow more complex. The NRE skin described in NRE research is focused squarely on safety and reflexes, not emotion, but it sits on the same spectrum of brain inspired computing that underpins more advanced AI. Policymakers and ethicists will need to decide how to talk about these systems, and whether certain kinds of behavior or appearance should trigger special protections, long before robots come close to anything like human consciousness. For now, the practical priority is clear: use pain like responses to keep people safe, while being honest about what machines do and do not feel.

What comes next for robot skin

Looking ahead, I expect the next wave of work on robot skin to focus on integration and scale. The Chinese NRE prototype and the high density tactile skins developed elsewhere show that the core sensing and neuromorphic processing pieces are already in place. The challenge is to cover entire humanoid bodies without gaps, maintain performance over years of use and connect these skins to higher level AI systems that can interpret patterns of contact as social cues, not just physical threats. A robot that can tell the difference between a child’s hug and an accidental shove, and respond appropriately, would be a powerful tool in education and care settings.

There is also room for cross pollination between projects. The flexible skin that can read signals from over 860,000 tiny pathways offers a template for ultra dense sensing, while the Chinese NRE design shows how to embed neuromorphic reflexes directly into the material. Combining those strengths could yield skins that are both incredibly detailed and incredibly fast, a combination that would make humanoid robots far more capable in cluttered, unpredictable environments. As Jun and other researchers push the limits of what artificial skin can do, the line between metal and flesh will not disappear, but it will become more porous than ever before.

More from MorningOverview