Engineers at MIT have taken a metal that usually trades strength for lightness and pushed it into an entirely new class, creating a 3D printable aluminum alloy that is reported to be roughly five times stronger than standard cast versions. Instead of relying on exotic elements or slow trial‑and‑error, the team used machine learning and laser powder bed fusion to redesign aluminum from the atomic scale up. The result is a material that behaves like a high‑end aerospace alloy but can be printed into intricate shapes that traditional casting or machining could never reach.

That combination of strength, low weight and geometric freedom is not just a lab curiosity, it directly targets some of the most demanding parts in aviation, energy and electronics. If the alloy performs in full‑scale components the way it has in test coupons, it could reshape how fan blades, structural brackets and even data‑center cooling hardware are designed and manufactured over the next decade.

How MIT’s alloy breaks the aluminum trade‑off

Aluminum has long forced designers into a compromise: it is light and easy to cast, but once you push for very high strength, it tends to become brittle, difficult to weld and prone to cracking during 3D printing. According to MIT, the new composition sidesteps that trade‑off, delivering parts that reach about five times the strength of standard cast aluminum while still behaving like a printable powder. That performance, described in an analysis of According to MIT, puts the alloy in the same league as some of the strongest aluminum grades made with conventional processes.

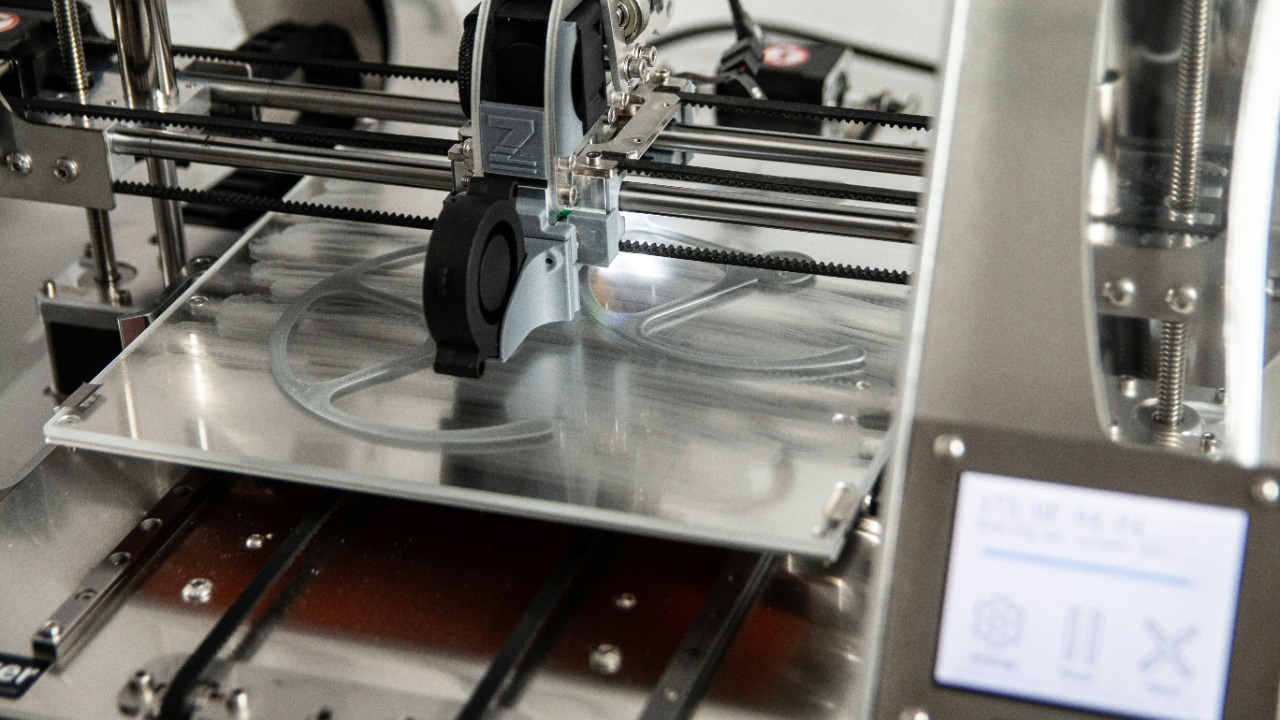

Instead of simply copying existing aerospace alloys, the researchers tuned the microstructure so that the metal forms a dense network of strengthening phases when it is melted and rapidly solidified by a laser. That is crucial, because in metal 3D printing the material is repeatedly heated and cooled in tiny pools, a cycle that can easily create pores and hot cracks. By designing the alloy around the realities of laser powder bed fusion rather than forcing a legacy recipe into a new process, the team effectively created a new category of aluminum that is both ultra strong and inherently compatible with additive manufacturing.

Why conventional aluminum struggles in 3D printing

Traditional alloy development has been painfully slow, with researchers mixing and casting countless compositions, then testing each one to see whether it meets a target strength or toughness. As one overview of the field notes, Traditionally this trial‑and‑error cycle can drag on for months or even years before a single promising candidate emerges. That slow pace has left many metal 3D printers relying on alloys originally designed for casting, even though the thermal conditions in a laser powder bed are completely different from those in a mold.

In metal casting, molten aluminum is poured into a relatively large cavity that cools at a moderate rate, which gives time for certain strengthening phases to form but also allows defects to grow. In laser powder bed fusion, by contrast, a focused beam scans across a thin layer of powder, creating tiny melt pools that solidify in milliseconds. As detailed in the same technical coverage, molten aluminum in this environment faces a high threshold for avoiding hot tearing and porosity. Many standard alloys simply cannot survive that thermal shock without cracking, which is why a purpose‑built composition is so significant.

From classroom challenge to lab breakthrough

The project did not begin as a top‑down industrial program but as a teaching experiment. In a 2020 MIT class, materials scientist Greg Olson challenged students to design a stronger printable aluminum alloy that could exploit the unique cooling rates of laser powder bed fusion. That classroom exercise seeded the idea that aluminum could be re‑engineered specifically for additive manufacturing rather than adapted from casting recipes. As the concept matured, it evolved into a full research effort that combined computational design, experimental printing and mechanical testing.

MIT’s role was not limited to theory. The team built and refined its own process parameters on in‑house printers, then partnered with external labs to validate the results. According to a detailed account of how the work unfolded, MIT engineers systematically mapped how small changes in composition and laser settings affected crack formation, density and strength. That iterative loop between classroom ideas, simulation and real hardware is what ultimately turned a student challenge into a material that now rivals the best conventional aluminum alloys.

Machine learning as a materials design engine

What sets this alloy apart is not only its performance but the way it was discovered. Instead of manually exploring a narrow set of compositions, the researchers used machine learning to scan a vast design space and predict which combinations of elements would produce the desired microstructure under laser processing. As one technical summary explains, the team applied data‑driven models to identify candidate alloys that would form stable strengthening phases without triggering the hot cracking that plagues many printable metals, a strategy highlighted in coverage of how By applying machine learning techniques they could leapfrog aluminum made using conventional manufacturing.

Once the model flagged promising compositions, the group printed test coupons and measured their density, microstructure and mechanical properties, feeding the results back into the algorithm. That closed loop allowed them to converge on a formulation that not only reached the target strength but also printed reliably across a range of geometries. The approach shows how artificial intelligence can compress years of metallurgical experimentation into a much shorter cycle, especially when the goal is to tailor alloys to the extreme thermal gradients of laser powder bed fusion rather than to the slower cooling of castings or forgings.

Printing crack‑free parts with powder tailored for lasers

Even the best alloy design is useless if it cannot be turned into a high quality powder that flows, melts and solidifies correctly in a printer. In this case, the team produced a feedstock whose particles had the right size distribution and surface chemistry to support dense builds. Reports on the work note that Powder made from this composition was successfully printed into dense, crack‑free parts, a critical milestone because many high strength aluminum alloys tend to fracture along grain boundaries during solidification.

After the initial builds, the researchers subjected the printed parts to a carefully tuned heat treatment to further optimize their microstructure. According to the same technical account, After heat treatment for eight hours, the alloy developed a fine dispersion of strengthening phases that pushed its mechanical performance into the range of the strongest cast aluminum grades. The fact that this could be achieved within a large design space, rather than at a single narrow set of parameters, suggests that the material has enough process robustness to be used in real industrial environments where printers and geometries vary.

Validating strength with LPBF and international testing

To prove that the alloy’s performance was not limited to a single lab setup, the team worked with partners abroad. Using their in‑house LPBF system, a German team printed small samples that captured the fine features and thermal histories typical of real components. Those samples were then shipped back to MIT for rigorous mechanical testing, including tensile strength, fatigue and fracture toughness. This cross‑border workflow helped confirm that the alloy’s behavior was not an artifact of a single machine or operator.

The results were striking. According to a detailed summary of the testing campaign, Using that LPBF setup the printed metal achieved strength levels comparable to or exceeding high end cast aluminum alloys, while maintaining the fine feature resolution that additive manufacturing is known for. That combination of validated strength and geometric fidelity is what makes the material relevant for demanding applications like aircraft structures, where both mechanical performance and precise shapes are non negotiable.

How it stacks up against conventional aluminum

For decades, the benchmark for strong aluminum parts has been alloys produced through casting, forging and subsequent heat treatment. These materials power everything from automotive suspension components to aerospace brackets, but they are limited in the shapes they can take and often require extensive machining. According to a synthesis of the MIT results, the new printed alloy performed on par with the strongest aluminum alloys currently produced through traditional casting, a claim backed by testing that showed the 3D printed metal could match the strength of aluminum made using standard manufacturing techniques as reported in MIT researchers.

What changes the equation is that this performance is now available in complex, lightweight structures that can be printed directly from a digital file. Instead of machining away most of a billet to leave a thin, optimized bracket, engineers can design lattice‑reinforced ribs, internal cooling channels or topology‑optimized trusses that only additive manufacturing can produce. As one overview of the work notes, MIT Engineers Create a 3D‑printable aluminum that is 5 Times Stronger Than Conventional Alloys while still enabling that kind of design freedom, which is a very different proposition from simply swapping one cast alloy for another.

Implications for aircraft, engines and data centers

The most immediate beneficiaries of this alloy are likely to be aerospace and energy systems, where every kilogram saved translates into fuel, range or payload. Today, fan blades for jet engines are typically made from titanium, which is over 50 per cent heavier and up to 10x more expensive than aluminum. If a printed alloy can approach titanium’s strength while retaining aluminum’s low density and cost, engine makers could redesign blades and structural frames to be lighter and cheaper without sacrificing safety margins. The same report points to potential uses in heat exchangers and cooling devices for data centres, where complex internal channels and high thermal conductivity are at a premium.

Beyond individual parts, the shift to metal 3D printing, also called additive manufacturing, promises shorter supply chains and lower costs in manufacturing. As one industry analysis notes, Today metal 3D printing is already being used to consolidate multi‑part assemblies into single components, reduce tooling and enable on‑demand production. A printable aluminum that rivals the best cast alloys could accelerate that trend, especially in sectors like aviation and high performance computing where both weight and thermal management are critical design drivers.

Why this alloy matters beyond MIT

Although the work originated at MIT, its implications reach far beyond a single campus. According to a detailed technical summary, Reardon Metal, Reimagined is not just a catchy phrase but a signal that aluminum, once seen as a mature and fully optimized material, still has room for radical improvement when paired with new design tools and manufacturing methods. The fact that the alloy can be printed into dense, crack‑free parts and then heat treated to reach fivefold strength over standard cast aluminum suggests that other common metals, from steels to nickel superalloys, may also be ripe for similar reinvention.

From my perspective, the most important shift here is conceptual rather than purely technical. Instead of treating additive manufacturing as a way to print existing alloys, the MIT team treated it as a new physical environment that demands its own materials, microstructures and design rules. That mindset, supported by machine learning and rigorous testing, is what allowed them to create Printable Aluminum that is genuinely Times Stronger Than Conventional Alloys and to position it as Lightweight Strength for Extrem applications. If industry follows that lead, the next decade of metal 3D printing will be defined less by the machines themselves and more by the tailored materials that run inside them.

More from MorningOverview