Nvidia’s data center chips have become the default engine for modern artificial intelligence, but they are not just faster versions of gaming graphics cards. The company’s AI accelerators strip away display baggage, add deeply specialized math hardware, and plug into server racks like miniature supercomputers, which is why cloud providers and enterprises treat them as a different class of silicon entirely. To understand what makes them special compared with standard GPUs, I need to unpack how they are built, how they are deployed, and why their surrounding ecosystem matters as much as raw teraflops.

From graphics workhorse to AI specialist

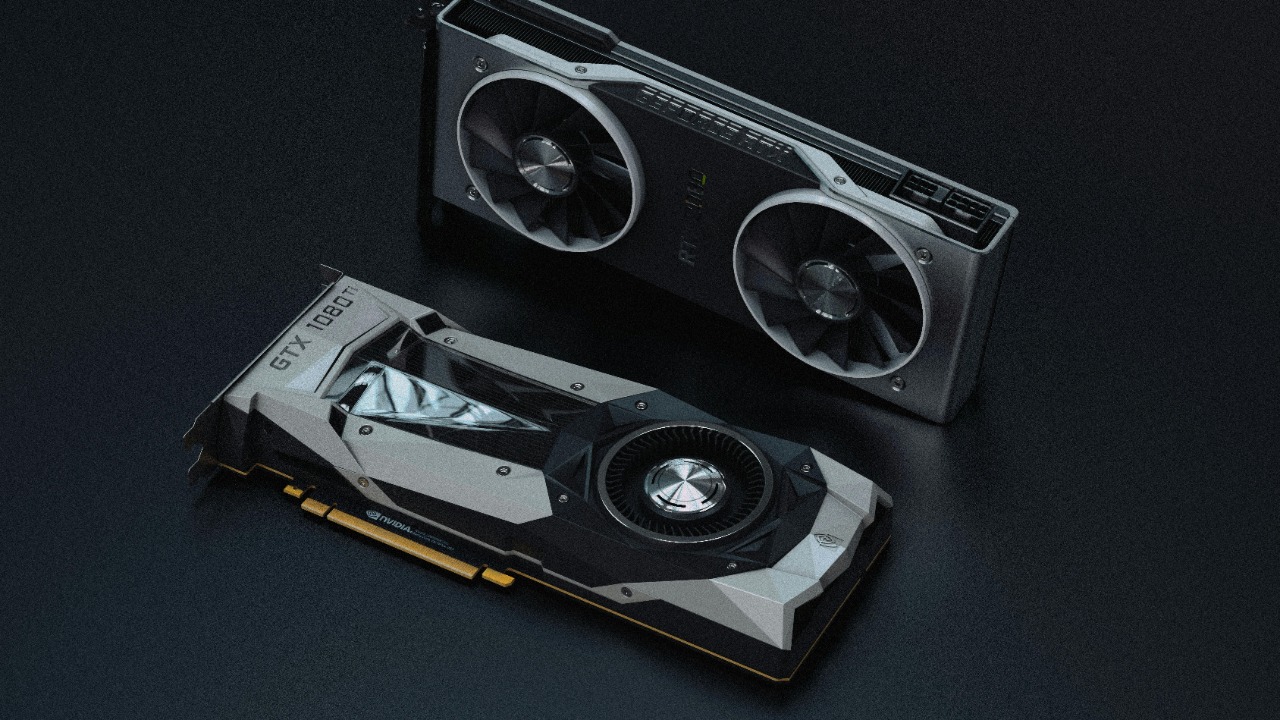

At a basic level, both a gaming card and an Nvidia AI accelerator start from the same idea, a massively parallel processor that can juggle thousands of small tasks at once. Traditional GPUs were created to draw pixels and triangles, so they carry display controllers, video outputs, and logic for handling screens and user interfaces. Nvidia’s dedicated accelerators remove that screen handling and focus entirely on compute, so every watt and every square millimeter of silicon is tuned for matrix math instead of rendering frames, which is why they are described as purpose built for AI rather than general graphics.

That specialization shows up in how workloads are scheduled and how memory is organized. A regular GPU must share resources between graphics pipelines, compute shaders, and sometimes even desktop compositing, while an accelerator is designed so that AI tasks can run without getting in each other’s way, with firmware and drivers tuned for long running training jobs instead of interactive games. Reporting on Nvidia’s server parts notes that this shift away from display logic toward pure compute is one of the core differences highlighted when explaining why AI accelerators behave differently from regular GPUs in data centers.

Tensor Cores and math engines built for neural networks

The real magic in Nvidia’s AI lineup sits in its dedicated math units, branded as Tensor Cores, which are designed to chew through the matrix multiplications that dominate neural network training and inference. Instead of treating AI as just another compute shader, these cores operate on blocks of numbers in formats like FP16, BF16, or newer low precision types, delivering far more throughput per clock cycle than the standard CUDA cores that power gaming workloads. That is why the company describes The NVIDIA A100 Tensor Core GPU as a device that delivers unprecedented acceleration for AI, data analytics, and HPC.

With the H100 generation, Nvidia doubled down on this approach, adding fourth generation Tensor Cores and a dedicated Transformer Engine that can dynamically choose precision to keep large language models running efficiently. Analysis comparing A100 and H100 notes that these Tensor Cores and the Transformer logic give H100 more efficiency when running modern AI models, particularly in multi tenant environments where every watt and rack unit counts. That kind of silicon level tailoring for neural networks simply does not exist in older gaming oriented GPUs, which still lean on more generic floating point units.

Memory and bandwidth: HBM versus GDDR

One of the least visible but most important differences between accelerators and standard GPUs is memory. Consumer cards like the RTX 4090 or workstation boards such as the RTX Pro 6000 typically use GDDR memory, which is fast but optimized for cost and gaming style access patterns, while data center accelerators rely on stacked high bandwidth memory that sits much closer to the compute cores. The A100 uses HBM2e and the H100 moves to HBM3, a progression that a technical comparison of Memory and Bandwidth highlights as critical for handling very large models and datasets.

Capacity matters just as much as speed. The H100 typically ships with 80 GB of HBM3, while a workstation card like the RTX Pro 6000 features 96 GB of GDDR7, a difference that underlines how Nvidia segments its products for datacenter training versus desktop content creation. Reporting on H100 vs RTX Pro 6000 stresses that the GDDR7 equipped board is aimed at workstations, while the H100’s HBM3 is tuned for data center training, where sustained bandwidth and low latency access to massive parameter arrays matter more than peak frame rates.

Architectural trade offs: RTX versus H100 and L40S

Even when Nvidia uses the same basic architecture across product lines, the company makes deliberate trade offs between flexibility and specialization. RTX A series cards keep full graphics pipelines and display outputs because they must serve as both compute engines and visualization tools in workstations, while H100 class accelerators strip those away to maximize density and power efficiency in server racks. A technical breakdown of What separates RTX A series and H100 notes that RTX parts are built for a mix of visualization and compute, while H100 is optimized for pure throughput in AI workloads.

Nvidia’s L40S illustrates how the company now blurs the line between GPU and accelerator for some enterprise tasks. The L40S is described as being designed to handle next generation data centre workloads, including large language model, or LLM, inference and high performance computing environments, yet it still carries the L series branding that historically pointed to visualization. That hybrid positioning shows how Nvidia is carving out tiers within its own stack, with H100 and successors at the top for training, L40S and similar parts for inference and mixed workloads, and RTX A series for smaller scale deep learning tasks that a comparison of A100, H100, and RTX A6000 describes as use cases for smaller scale deep learning.

Blackwell Ultra and the “AI factory” mindset

Nvidia’s latest architecture, Blackwell Ultra, shows how far the company has moved from the mindset of a graphics vendor to that of an AI infrastructure supplier. The Blackwell Ultra GPU is described as building on the previous generation to power what Nvidia calls the AI factory era, with changes that focus on sustained performance rather than just peak benchmarks. Technical documentation notes that the result is higher sustained throughput and improved Inside NVIDIA Blackwell Ultra NVFP4 performance, a low precision format tailored for generative models.

That focus on factories rather than individual servers reflects how accelerators are now deployed. Instead of a single card in a workstation, Blackwell Ultra parts are meant to be wired together in pods and clusters, with high speed interconnects and shared memory pools that let them behave like one giant accelerator. This is a very different design target from a gaming GPU, which is usually sold as a standalone board, and it explains why Nvidia’s AI chips are increasingly described as the heart of an The NVIDIA Blackwell Ultra GPU powered AI factory rather than just another component.

System level design: DGX, DPUs, and AI supercomputers

What truly separates Nvidia’s accelerators from standard GPUs is how they are packaged into complete systems. The company’s DGX line is often described as a “DGX – Supercomputer in a Box,” bundling multiple accelerators, high speed networking, and storage into a turnkey AI training appliance. Reporting on Nvidia’s rise notes that by making use of DPUs to offload networking and storage tasks, these systems free the GPUs to focus entirely on AI compute, a design that has appealed to cloud providers like Microsoft and Amazon that want predictable performance at scale.

This system level thinking extends to how accelerators are integrated into enterprise stacks. Dell, for example, lists the NVIDIA L40 GPU as one of the acceleration components used in its generative AI solutions, emphasizing that it supports both training and inference for workloads that need to deliver the best personalized experiences. That kind of curated hardware plus software stack is not how consumer GPUs are sold, and it underlines why accelerators are treated as infrastructure, closer to a mini supercomputer than a graphics card.

Performance, efficiency, and the cost of specialization

Raw performance is the headline reason accelerators dominate AI training, but efficiency is the quieter advantage that matters in data centers. A comparison of A100 and H100 notes that the newer chip offers more Efficiency when running modern AI models, thanks to its updated Tensor Cores and Transformer Engine, which translate into lower energy use per token generated or per training step. In multi tenant environments where many customers share the same hardware, that efficiency headroom is what allows providers to pack more jobs onto the same cluster without blowing through power and cooling limits.

Comparisons with high end consumer GPUs make the trade offs even clearer. The RTX 4090, for instance, includes 16,384 CUDA cores and delivers enormous gaming performance, yet analyses of Comparing NVIDIA H100 and RTX 4090 point out that the H100’s architecture, memory, and interconnects make it far better suited to large scale machine learning workloads. IBM’s overview of accelerators versus GPUs notes that Standard AI accelerators are specialized for AI tasks, often delivering higher performance and improved energy efficiency compared with general purpose GPUs that must juggle a wider range of duties.

Software ecosystem and developer experience

Hardware alone does not explain Nvidia’s lead, and here the distinction between accelerators and standard GPUs blurs, because both rely on the same CUDA programming model. What changes is the depth of software support around the accelerators, from libraries that exploit Tensor Cores to orchestration tools that spread training across dozens or hundreds of cards. IBM’s discussion of accelerators emphasizes that specialization is not just about silicon, it is also about the libraries of tools and resources that come with them, which in Nvidia’s case includes everything from cuDNN and TensorRT to enterprise ready drivers and monitoring stacks.

For enterprises, that ecosystem translates into predictability. Dell’s generative AI reference architectures, for example, do not just list which accelerators they support, they also specify the software layers that sit on top, from container runtimes to model serving frameworks. In practice, that means a data scientist can move a model from a development workstation with an RTX card to a production cluster of H100s or L40S boards with minimal code changes, while still benefiting from the accelerators’ efficiency and scale. IBM’s overview also notes that, generally speaking, a GPU must balance graphics and compute, while Standard accelerators can be tuned for improved energy efficiency as well, which is exactly what Nvidia’s software stack is designed to expose.

Choosing between accelerators and regular GPUs

For all their advantages, Nvidia’s AI accelerators are not always the right choice, especially for smaller teams or mixed workloads. Workstation oriented GPUs like the RTX A6000 or RTX Pro 6000 offer a more flexible balance of graphics and compute, and they can still handle serious deep learning tasks when models fit within their memory limits. Comparisons of A100, H100, and RTX A6000 point out that the RTX card is better suited to smaller scale deep learning tasks, where the overhead of a full data center accelerator and its infrastructure would be overkill.

At the other end of the spectrum, enterprises that are building large language model services or recommendation engines at global scale increasingly see accelerators as non negotiable. Dell’s documentation on NVIDIA accelerators in generative AI stacks, along with Nvidia’s own positioning of DGX systems as supercomputers in a box, shows how these chips have become the backbone of AI infrastructure rather than optional upgrades. For organizations making that leap, the choice is less about whether accelerators are special compared with standard GPUs, and more about how quickly they can secure enough of them to keep up with the models they want to run.

The broader product landscape and market pull

Nvidia’s catalog now spans a wide range of AI focused products, from the A100 and H100 to more specialized boards that appear in retail listings without much fanfare. Product entries for data center GPUs and other accelerator cards show how these devices are now sold as standalone components to system builders and cloud providers, not just as part of Nvidia branded servers. That breadth lets the company target everything from edge inference boxes to massive training clusters, all while keeping developers within the same CUDA and Tensor Core ecosystem.

At the same time, workstation and prosumer cards continue to evolve, with listings for professional RTX boards and other GPUs that blur the line between graphics and AI. Some of these products, such as those referenced in workstation GPU listings, carry enough memory and Tensor Core capability to serve as entry level AI accelerators in their own right. That overlap can make the market look crowded, but the underlying pattern is clear: the more a chip is optimized for AI, the more it starts to resemble Nvidia’s flagship accelerators in design, deployment, and the ecosystem that surrounds it.

More from MorningOverview