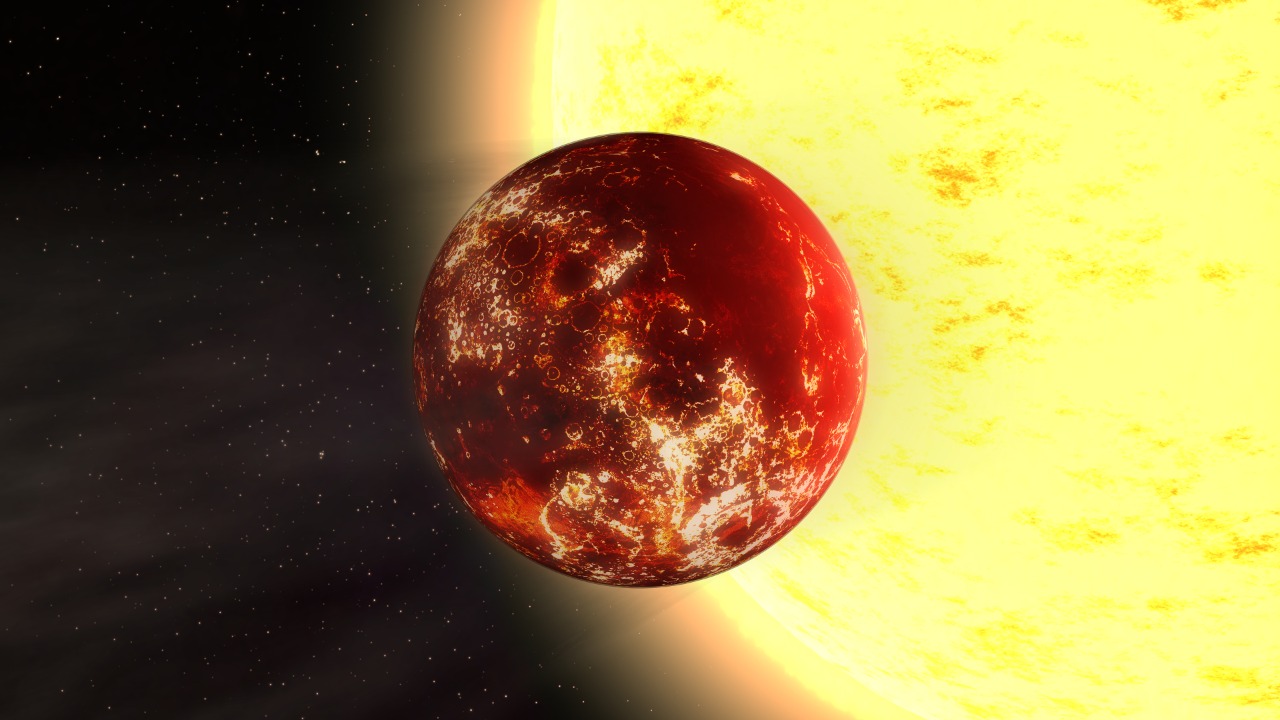

When astronomers first cataloged some of the closest orbiting rocky exoplanets, they wrote them off as bare, airless cinders, worlds so close to their stars that any atmosphere should have been blasted away. Now the James Webb Space Telescope has turned its infrared gaze back to one of those supposed dead rocks and instead revealed a broiling globe of molten rock wrapped in unexpected gases. The discovery transforms a planetary corpse into a laboratory for lava, atmospheres and the extremes of planetary survival.

What Webb is uncovering is not a gentle Earth twin but a “wet lava ball,” a place where rock behaves like water and dayside temperatures can keep entire hemispheres molten. Yet against expectations, this inferno appears to cling to a substantial envelope of gas, challenging long-held theories about how small, hot planets evolve and how long their atmospheres can endure so close to a star.

From “dead rock” to lava world

The planet at the center of this rethink is a rocky world so close to its star that it completes an orbit in less than a day, a configuration that once led researchers to assume it was little more than a scorched stone. Early measurements suggested a dense, compact body with a surface hot enough to melt silicate rock, the kind of place where any volatile molecules should be stripped away by relentless stellar radiation. In that picture, the planet’s dayside was imagined as a static, glowing crust, a final state for worlds that wander too close to their suns.

Webb’s new observations overturn that simple narrative. By watching the planet disappear behind its star and then re-emerge, astronomers have measured the heat pouring from its dayside and found signatures that point to a dynamic, magma-covered surface and a thick shroud of gas. One report describes how JWST Looked Closer at a so-called Dead Rock Planet, What It Found Was a world whose dayside glow is best explained by a vast magma ocean and heat re-radiated through an atmosphere, not a bare, cooling crust.

Meet TOI‑561 b, the blazing rule breaker

The poster child for this new class of infernal yet surprisingly complex worlds is TOI‑561 b, a rocky exoplanet that hugs its star so tightly that its year is measured in hours rather than days. It is part of a compact system of at least three planets, with the innermost, TOI‑561 b, enduring the most intense stellar bombardment. Earlier work already hinted that this planet was both ancient and unusually hot, but the expectation was that such a world would have long since lost any atmosphere to space.

Fresh analysis using the James Webb Space Telescope now indicates that TOI‑561 b likely carries an atmosphere despite its extreme environment. One detailed study notes that New research suggests this rocky “lava planet” orbiting very close to its star likely carries an atmosphere, turning it into a crucial test case for how alien air can persist on small, hot worlds and what that might reveal about the origins of atmospheres in our own solar system.

A lava world that refuses to go bare

For years, the prevailing wisdom held that planets like TOI‑561 b should be stripped clean, their gases boiled off by ultraviolet light and stellar winds until only naked rock remained. That expectation was not just a hunch, it was built into models of atmospheric escape that predicted small, close-in planets would quickly lose their envelopes. The discovery that this particular lava world still wears a substantial cloak of gas forces theorists to revisit those models and ask what they missed.

Observers now describe TOI‑561 b as a lava world that “refuses to go bare,” a phrase that captures how stubbornly its atmosphere seems to cling to the planet despite the odds. In a broader review of recent discoveries, Astronomers using JWST highlight this planet as an example of an atmosphere clinging to a world that, by all previous calculations, should have been bare, reshaping ideas about which planetary atmospheres can survive and for how long.

How JWST reads heat from a molten hemisphere

To turn a faint, distant point of light into a physical portrait of a lava-covered planet, the James Webb Space Telescope relies on exquisitely sensitive infrared measurements. When the planet passes behind its star, the total light from the system dips slightly, and by comparing the system’s brightness before and during that eclipse, scientists can isolate the glow from the planet’s dayside. That glow carries information about temperature, surface state and whether heat is being redistributed by an atmosphere or simply radiating straight into space.

In the case of TOI‑561 b, the dayside emission is too muted and too smooth to match a bare rock radiating directly from a static magma ocean. Instead, the data fit a scenario in which a thick atmosphere absorbs and re-emits heat, softening temperature contrasts and hinting at vigorous circulation. One analysis describes how Now the innermost of the three planets in the system shows the best evidence yet of a lava world with a thick atmosphere, a conclusion drawn from the way its dayside heat signature deviates from the expectations for a bare, molten surface.

From 55 Cancri e to a new class of “hell planets”

TOI‑561 b is not the first ultra hot rocky world to challenge assumptions about atmospheres. Earlier observations of 55 Cancri e, another close orbiting super Earth, hinted that even at extreme temperatures, rocky planets can maintain envelopes of gas that interact with magma oceans. In that case, scientists used Webb to search for atmospheric gases around a planet that orbits its star in less than a day and found signs consistent with a volatile rich shroud rather than a naked rock.

Those initial hints came when Researchers using NASA‘s James Webb Space Telescope reported a possible atmosphere surrounding the rocky exoplanet 55 Cancri e, a hot world in the Cancri system that opened the door to a new type of science focused on magma ocean planets. That earlier result set the stage for the more definitive evidence now emerging from TOI‑561 b and similar “hell planets,” suggesting that such worlds may form a broader class where molten surfaces and dense atmospheres evolve together.

“Wet lava ball” physics and violent winds

What makes these planets so intriguing is not just that they are hot, but that their heat drives exotic physics. On a world where the surface is a global magma ocean, rock can evaporate into the atmosphere, condense on the nightside and literally rain back down as minerals, creating a rock cycle in the sky. The presence of an atmosphere turns that surface into a “wet lava ball,” where molten rock and gas exchange material and energy in ways that have no direct analogue on Earth.

Circulation models suggest that such an atmosphere would be anything but calm. Strong temperature contrasts between the blazing dayside and the relatively cooler nightside can drive supersonic winds that redistribute heat and material. One report notes that Strong winds would cool the dayside by transporting heat over to the nightside, a process that helps explain why the observed dayside temperatures are lower than a bare rock model would predict and why the planet’s thermal emission appears more uniform than expected.

Challenging the old rules for small, hot planets

The emerging picture of TOI‑561 b and its kin directly challenges the long standing rule of thumb that small, close in planets cannot hold on to thick atmospheres. Traditional models assumed that intense stellar radiation would drive rapid atmospheric escape, especially for lighter molecules, leaving behind only a thin veneer of heavy elements or nothing at all. The new data show that reality is more complicated and that some rocky planets can maintain substantial gaseous envelopes even while bathed in fierce starlight.

In fact, the findings explicitly push back on the idea that relatively small planets in ultra short orbits must be bare. One analysis of the James Webb Space Telescope results notes that James Webb Space Telescope observations challenge the prevailing wisdom that relatively small planets that orbit in under 11 hours must have lost their atmospheres, forcing theorists to revisit how composition, magnetic fields and outgassing might help such worlds resist erosion.

Alien atmospheres that “shouldn’t exist”

For planetary scientists, perhaps the most unsettling aspect of these discoveries is how they expose gaps in our understanding of which atmospheres are possible. The combination of extreme heat, small planetary size and close proximity to a star was supposed to be a recipe for atmospheric loss, yet Webb keeps finding counterexamples. These atmospheres do not just survive, they appear to be thick, dynamic and chemically rich, hinting at processes that current models only sketch in broad strokes.

That tension is captured in descriptions of a broiling “hell planet” whose atmosphere, by all prior expectations, should not exist. In one account, the James Webb telescope uncovers a new mystery in the form of a broiling world with an atmosphere that should not exist, underscoring how these observations are forcing a rethink of how atmospheres can form and evolve under conditions far more extreme than anything in our solar system.

Clues to exotic chemistry and planetary origins

Beyond the mere presence of an atmosphere, Webb’s spectra hint at unusual chemical makeups that may trace back to how and where these planets formed. If a lava world’s atmosphere is dominated by vaporized rock, its composition will reflect the minerals in its mantle and crust, potentially revealing whether it formed in place or migrated inward from a cooler, more distant region. Differences in the balance of elements like magnesium, silicon and iron could point to formation in a “very different chemical environment” from that of Earth and its neighbors.

That idea is echoed in comments from researchers who argue that at least one of these lava planets “must have formed in a very different chemical environment from planets in our own solar system,” a conclusion tied to the specific spectral fingerprints seen by Webb. In a detailed discussion of the data, Johanna Teske is quoted emphasizing that the planet’s atmospheric signal implies a formation history unlike that of the terrestrial planets we know, turning this “wet lava ball” into a probe of exotic planetary nurseries.

Rewriting the rulebook for “blazing exoplanets”

As more data accumulate, TOI‑561 b is emerging as a benchmark for a broader population of ultra hot rocky planets that defy expectations. These worlds are not just curiosities, they are stress tests for theories of planet formation, atmospheric escape and interior dynamics. Their very existence suggests that nature can assemble and preserve complex, atmosphere bearing planets under conditions that once seemed utterly hostile to anything but bare rock.

One analysis frames TOI‑561 b as part of a group of “blazing exoplanets” that break all the rules about alien atmospheres, highlighting how it is both hot and old yet still wrapped in gas. In that account, This Blazing Exoplanet Breaks All the Rules about Alien Atmospheres, JWST Finds, because it is hot, small and ancient and, against all prior expectations, it has one, forcing scientists to expand their rulebook for how atmospheres behave on the most extreme rocky worlds.

What comes after the first “dead planet” resurrection

The transformation of a supposed dead rock into a lava filled inferno with a thick atmosphere is not just a single dramatic story, it is a preview of what Webb can do for the study of rocky exoplanets. Each new observation adds another point to a growing map of how temperature, stellar type, planetary mass and composition interact to shape atmospheres. As more ultra hot worlds are observed across different systems, patterns will emerge that either reinforce or overturn the early lessons from TOI‑561 b and 55 Cancri e.

For now, the clearest takeaway is that the James Webb Space Telescope is opening a new frontier in the study of rocky planets, one where molten surfaces and dense atmospheres coexist in ways that were barely imagined a decade ago. The initial hints from 55 Cancri e, the detailed portrait of TOI‑561 b and the broader population of “hell planets” with atmospheres that should not exist all point in the same direction: the universe is far more inventive with its rocky worlds than our early models allowed, and what once looked like dead rocks may instead be some of the most dynamic planets in the galaxy.

More from MorningOverview