As people grow older, their immune systems do not simply slow down, they often become locked into a simmering, self-perpetuating state of inflammation. Emerging work now suggests that aging immune cells may actively rework their own DNA to keep this inflammatory program switched on, blurring the line between damage and deliberate adaptation. I want to unpack how this genomic tinkering fits into the broader story of “inflammaging,” why it matters for diseases from heart failure to long COVID, and how scientists are starting to push these cells back toward a more youthful state.

The strange persistence of inflammaging

One of the most striking features of older bodies is not a single disease but a background hum of immune activity that never quite shuts off. Researchers use the term Inflammaging to describe this chronic, low grade inflammation and the persistent secretion of proinflammatory cytokines that reshape tissues even in the absence of overt infection. Instead of the sharp spike and clean resolution that follow a flu shot or a scraped knee, older immune systems often sit in a half-activated state, with signaling molecules like interleukins and chemokines quietly nudging organs toward fibrosis, metabolic disruption, and frailty.

This smoldering response is not just a background curiosity, it is a shared risk factor that links conditions as diverse as type 2 diabetes, some forms of cardiovascular disease, neurodegeneration, and even poor vaccine responses. When I look across the data, what stands out is how often age related illnesses track with markers of this low level immune activation rather than with any single pathogen. The idea that immune cells might be editing their own DNA to preserve this inflammatory identity adds a new twist: instead of being passive victims of accumulated damage, some of these cells may be actively locking in a maladaptive survival strategy that keeps the inflammatory loop running.

DNA damage, repair, and a feedback loop with inflammation

At the molecular level, aging cells accumulate a steady burden of broken and miscopied DNA. According to work summarized in an Abstract on mice, Persistent DNA lesions build up with aging and trigger inflammation, which is described as the body’s first line of immune defense strategy and a driver of the onset of aging associated diseases. When repair pathways fail to fully patch these lesions, fragments of DNA can leak into the cytoplasm, where innate immune sensors mistake them for viral genomes and launch alarm programs that include interferons and other inflammatory mediators. In that sense, the genome itself becomes a chronic irritant.

What makes this feedback loop especially pernicious is that inflammation can, in turn, generate more DNA damage through oxidative stress and other reactive byproducts. The same study on Persistent DNA damage in mice highlights how this cycle of lesions and immune activation accelerates tissue dysfunction and shortens healthspan. When I connect this to the idea of immune cells rewriting their own DNA, it suggests a spectrum: some changes are accidental scars from failed repair, while others may be more targeted edits that stabilize an inflammatory identity. Either way, the end result is similar, a cell that treats its own genome as both a sensor and a script for chronic alarm.

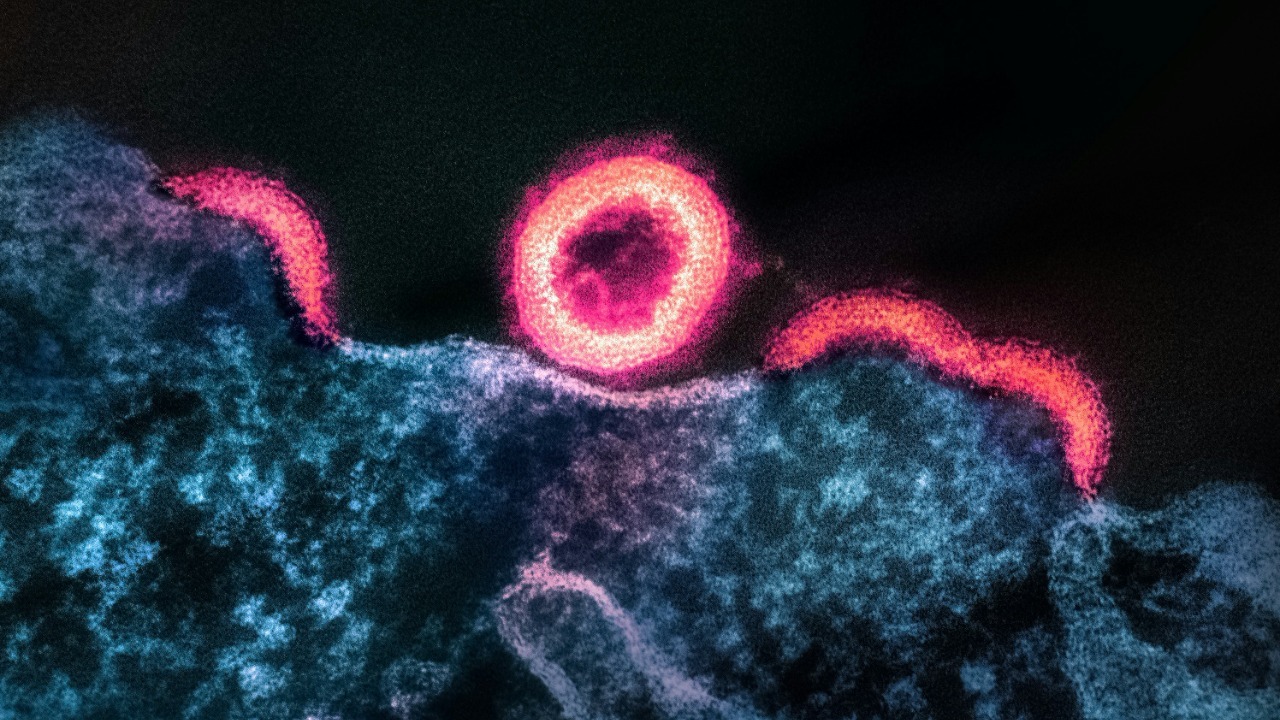

Immune cells that rewrite their own code

Recent work has sharpened that picture by showing that certain immune cells do not just suffer DNA damage, they may actively reshape their genetic landscape to stay inflammatory. Scientists described a pathway in which aging immune cells appear to rewrite their own DNA to maintain a proinflammatory state, a finding highlighted in a report titled Aging Immune Cells May Rewrite Their Own DNA To Stay Inflammatory. In that work, the researchers, referred to collectively as Scientists, identified specific molecular machinery that alters DNA structure and accessibility in older cells, effectively reprogramming them to favor inflammatory gene expression over more balanced responses.

From my perspective, this is a crucial shift in how we think about immune aging. Instead of viewing older immune cells as simply exhausted or senescent, this pathway suggests that some of them are actively choosing, at the molecular level, to become long lived instigators of inflammation. The fact that Scientists could pinpoint a defined pathway means it is not just random decay but a potentially druggable process. If we can interrupt the enzymes or regulatory proteins that drive this DNA rewriting, we might be able to coax these cells back toward a more youthful, flexible state rather than letting them dominate tissues with a rigid inflammatory script.

Epigenetic drift: methylation changes that lock in age

Beyond outright DNA breaks or structural edits, aging immune cells also undergo more subtle epigenetic changes that influence which genes are turned on or off. A study published in Aug examined aging associated DNA methylation of a transcription factor called LEF1, using transcriptomic data from peripheral blood to identify biomarkers of immune aging. The authors reported that In this study, we identified aging-associated blood biomarkers and proposed LEF1 methylation as a potential target for aging related diseases. Methylation is a chemical tag that cells place on DNA to silence or dampen gene activity, and shifts in these tags with age can profoundly reshape immune behavior without altering the underlying sequence.

What I find compelling about the LEF1 work is that it shows how epigenetic drift can be both a marker and a mechanism of immune aging. If methylation of LEF1 reduces its ability to support balanced T cell development or function, then older immune systems may gradually lose regulatory capacity while favoring more inflammatory subsets. Because methylation patterns are, in principle, reversible, identifying specific age linked changes like those in LEF1 opens the door to therapies that do not need to cut or replace DNA. Instead, they could re tune the epigenetic landscape, loosening the grip of age locked programs and giving immune cells a chance to respond more like their younger counterparts.

The protein drivers behind age related inflammation

Genetic and epigenetic changes are only part of the story, they ultimately act through proteins that carry out the work of inflammation. A report from PAUL described how a new study identified a key protein that drives inflammation with age, focusing on how older adults develop a dysfunctional immune system that leaves them more vulnerable to disease. The researchers at PAUL and the College of Biological Sciences showed that this protein sits at a critical junction in immune signaling, amplifying inflammatory responses in older individuals even when the original trigger is modest, a finding summarized in a release that noted PAUL as a central institution in the work.

When I connect this protein level insight to the DNA rewriting and methylation changes described earlier, a layered picture emerges. Aging immune cells may alter their genome and epigenome in ways that favor the production or activation of specific inflammatory proteins, which then reinforce the very signals that maintain those genomic states. Interrupting this loop could mean targeting the protein directly with antibodies or small molecules, or going upstream to adjust the DNA and methylation patterns that control its expression. Either way, the PAUL findings underscore that inflammaging is not a vague, diffuse process, it is built from concrete molecular players that can, in principle, be dialed down.

T cells at the center of immune aging

Among all the immune cells that change with age, T cells stand out as both highly plastic and highly vulnerable. A feature on mRNA therapy for immune rejuvenation noted that “T cells, in particular, are one of the cell types that change the most during ageing,” quoting Mittelbrunn, who was not involved in the original experiments but emphasized how dramatically these cells remodel over time. In that same report, Mittelbrunn pointed out that T cells circulate through the body’s whole blood volume, which means any age related shift in their behavior can have system wide consequences, a point captured in the description that T cells, in particular, are one of the cell types that change the most during ageing.As people age, immune cells called T cells tend to decline in both quantity and quality, which weakens responses to new infections and vaccines while sometimes preserving or even expanding autoreactive and inflammatory subsets. The same mRNA therapy report highlighted how this decline contributes to susceptibility to some forms of cardiovascular disease and other chronic conditions, noting that As people age, immune cells called T cells tend to decline in both quantity and quality. When I think about DNA rewriting in this context, it is easy to imagine that long lived memory T cells, which are designed to persist for decades, might be especially prone to locking in maladaptive programs that favor chronic inflammation over nimble defense.

mRNA therapy and the prospect of immune rejuvenation

The same body of work that spotlighted Mittelbrunn’s comments also explored a provocative idea: using mRNA therapy to restore youth to old immune cells. Instead of editing DNA directly, these approaches deliver carefully designed mRNA molecules that instruct cells to temporarily produce proteins associated with a younger, healthier state. In experimental models, reprogramming old T cells with such mRNA cocktails has been shown to improve their proliferation, cytokine balance, and ability to clear infections, hinting that even deeply aged immune cells retain a surprising capacity for renewal when given the right signals.

From my vantage point, mRNA therapy sits at an interesting crossroads with the DNA rewriting story. If aging immune cells have edited their genomes or epigenomes to favor inflammation, then mRNA based interventions could act as a kind of overlay, imposing a youthful functional program on top of an aged genetic substrate. Over time, repeated pulses of such reprogramming might even push the underlying epigenetic marks in a healthier direction, although that remains speculative and, by the standards set here, Unverified based on available sources. What is clear from the mRNA work is that the immune system is not a one way street toward decline, and that even cells burdened with age related DNA changes can be coaxed into more balanced behavior.

Oxidative stress as the spark for genomic change

Behind many of these molecular shifts lies a familiar culprit: oxidative stress. As mitochondria and other cellular systems become less efficient with age, they leak reactive oxygen species that can nick DNA, oxidize bases, and interfere with repair enzymes. The review on oxidative stress in ageing and chronic degenerative pathologies emphasized how these reactive molecules feed directly into chronic inflammation, reinforcing the pattern of Inflammaging described earlier. In that framework, oxidative stress is not just a byproduct of aging but a driver that shapes the immune landscape by damaging DNA and nudging cells toward proinflammatory states.

What I find particularly important here is that oxidative stress provides a mechanistic bridge between lifestyle factors and the deep genomic changes seen in aging immune cells. Diets high in processed sugars, chronic exposure to pollutants, and sedentary behavior can all increase oxidative load, which in turn raises the likelihood of DNA lesions and maladaptive repair in immune cells. While the sources at hand focus more on molecular pathways than on specific interventions, the implication is clear: strategies that reduce oxidative stress, whether through pharmacology or behavior, could slow the pace at which immune cells accumulate the DNA scars and epigenetic marks that lock them into inflammatory roles.

Cardiovascular aging, long COVID, and the self reinforcing cycle

The consequences of an inflamed, genomically altered immune system are perhaps most visible in the cardiovascular system. A detailed review of inflammaging, immunosenescence, and cardiovascular aging described how chronic immune activation stiffens blood vessels, destabilizes plaques, and impairs repair mechanisms in the heart. The authors drew a direct line from these age related immune shifts to the complications seen in long COVID, where lingering viral antigens and dysregulated immune responses appear to amplify pre existing inflammatory circuits in older adults. They argued that Strategies aimed at breaking this self-reinforcing cycle may need to rejuvenate immune function rather than simply suppress it.

In that context, the idea that aging immune cells may have edited their own DNA to favor inflammation becomes more than a molecular curiosity, it is a potential explanation for why some older patients struggle to recover from infections like SARS CoV 2. If T cells and other leukocytes are locked into an inflammatory identity by genomic and epigenomic changes, then even after the virus is largely cleared, they may continue to damage blood vessels, heart tissue, and other organs. Breaking that cycle could require a combination of approaches: dampening the immediate inflammatory signals, targeting key proteins like those identified by PAUL, and, in the longer term, finding ways to reset the genomic programs that keep these cells stuck in an aged, inflammatory mode.

Where the science points next

Looking across these strands of research, I see a field that is rapidly moving from descriptive to intervention focused science. We now have evidence that Persistent DNA damage can trigger inflammation, that Scientists have mapped pathways by which aging immune cells rewrite their own DNA to stay inflammatory, that Aug era work on LEF1 methylation has identified specific epigenetic biomarkers of immune aging, and that PAUL linked a concrete protein to age related inflammatory dysfunction. Layered on top are emerging tools like mRNA therapy, which Mittelbrunn and others see as a way to restore youthful function to T cells that have been reshaped by age.

The challenge, and the opportunity, is to integrate these insights into coherent strategies that can be tested in real patients. That will mean figuring out which DNA changes are causal drivers of inflammaging and which are just passengers, deciding when it is safer to overlay new programs with mRNA versus attempting deeper epigenetic re editing, and identifying biomarkers, like LEF1 methylation, that can tell clinicians whether an intervention is actually rejuvenating the immune system. For now, the idea that aging immune cells may edit their own DNA to stay inflamed serves as both a warning and a roadmap: a warning that age related disease is written into our cells more deeply than we once thought, and a roadmap that points to the very scripts we might someday rewrite.

More from MorningOverview