Inside rooms designed to be among the most sterile places on Earth, scientists have just cataloged 26 forms of life that no one had ever seen before. The discovery inside NASA spacecraft facilities does not simply tweak the rulebook for planetary protection, it forces a rewrite of how I think about life’s ability to adapt, hide and hitch a ride to other worlds.

These newly identified bacteria are not random contaminants, they are specialists that have evolved to survive chemical scrubs, filtered air and relentless monitoring. Their presence in NASA cleanrooms raises urgent questions about how we search for life on Mars and beyond, and whether our own microbes might get there first.

How a “clean” room became a biodiversity hotspot

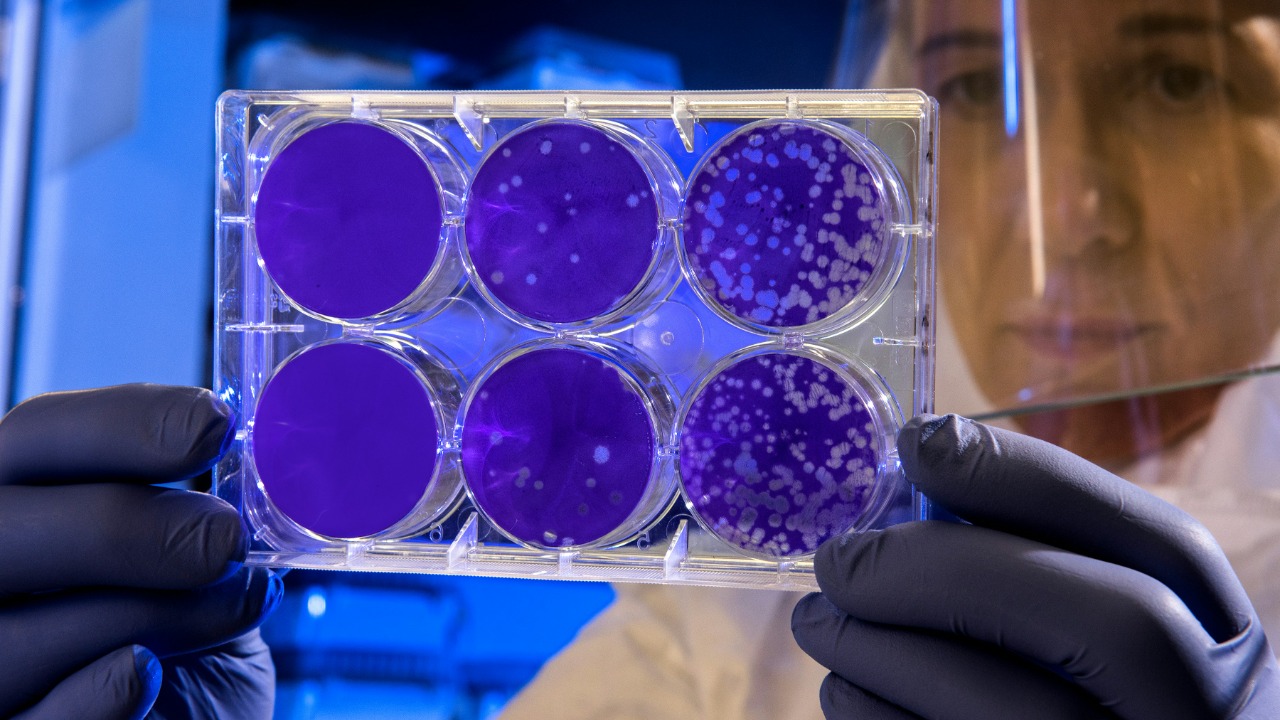

At first glance, a NASA cleanroom looks like the last place anyone would go hunting for new species. These facilities are built to keep spacecraft as free of Earth life as possible, with technicians in full-body suits, filtered airflow and strict protocols that treat a stray skin cell as a problem. Yet when Not and other Scientists systematically sampled surfaces around a spacecraft assembly area, they uncovered a hidden ecosystem that had quietly adapted to this artificial environment, including 26 microbe species that had never been cataloged before in any database.

What makes this so striking to me is that the cleanroom was not neglected or poorly run, it was operating as intended. The microbes that survived were not ordinary germs that slipped through the cracks, they were specialists that had endured repeated cleaning cycles and still managed to persist. According to the genomic work described in the study of the NASA facility, these hardy microbes may also be able to withstand conditions far harsher than a wiped-down floor, which is exactly what worries astrobiologists who want to keep Mars and other targets pristine for future life detection missions.

The Phoenix mission’s microbial legacy

The most detailed look at this hidden community comes from work tied to the Phoenix lander, which was sent to the Martian arctic to dig into ice and soil. During the Phoenix preparations, researchers collected swabs from the Kennedy Space Center, focusing on the Payload Hazardous Servicing Facili where the spacecraft hardware was processed. During the Phoenix campaign, they isolated a staggering 215 bacterial strains from these supposedly ultra-clean environments, a number that already hinted the microbial story was more complicated than the checklists suggested.

When those 215 strains were sequenced and compared, the surprise deepened. Furthermore, around 25% of the bacterial strains, specifically 53 out of 215 isolates, were identified as belonging to 26 novel species that had not been described in the scientific literature before. For me, that figure is the pivot point: it means that nearly one in four of the microbes clinging to Phoenix-era hardware and infrastructure did not match any known organism, even though they had survived in a place designed to exclude life. That is not a rounding error in planetary protection, it is a sign that our catalog of Earth microbes is still incomplete in the very places we scrutinize most.

Genes built for survival, not comfort

Once scientists realized how many unknown bacteria were living in the cleanrooms, the next question was obvious: what makes them so good at surviving there. Genomic analysis of the isolates showed that Many of these species possess genes that make them resilient to decontamination and radiation, traits that are exactly what a microbe would need to endure both the cleaning regimens on Earth and the harsh journey through space. When I look at that genetic toolkit, I see organisms that have been selected, intentionally or not, by the very procedures meant to eliminate them.

These survival genes are not abstract curiosities. They include mechanisms for repairing DNA damage, pumping out toxic chemicals and forming protective structures that help the cells ride out long periods of stress. In a normal hospital or office, such traits might give a bacterium a modest edge. In a NASA cleanroom, they are the difference between extinction and persistence. The fact that this evolutionary pressure has produced 26 novel species inside a facility built to be sterile underscores how quickly microbial life can adapt to human-made environments, even when those environments are designed to be hostile.

Extreme microbes that surrounded a Mars-bound robot

The story becomes even more unsettling when I follow it from the lab bench back to the spacecraft themselves. Never before had engineers realized just how many extreme microbes could cluster around a robot destined for another planet, yet DNA analysis has now revealed that a NASA robot sent to Mars 18 years ago was surrounded by organisms capable of surviving in space. Researchers reconstructed the microbial community that had coated parts of the hardware and found that it was dominated by extremotolerant species, including some of the same types now recognized as new to science.

Reporting on these findings shows that the microbes were not just sitting on a random floor tile, they were in the immediate vicinity of the Mars-bound equipment, in some cases on surfaces that would later be exposed to the vacuum and radiation of interplanetary travel. When I read that these extreme microbes surrounded the robot before launch, I cannot avoid the implication that at least some of them may have endured the trip. That possibility does not prove contamination of Martian soil, but it does mean that the line between a clean spacecraft and a biologically active one is far thinner than mission planners once assumed.

When “playing dead” becomes a survival strategy

One of the most intriguing twists in this story is that some of the cleanroom bacteria do not just resist cleaning, they evade detection by pretending to be dead. University of Houston Scientists Learn that a Rare Bacterium can effectively Plays Dead to Survive, entering a dormant state in which it shows no obvious signs of life yet remains capable of reviving when conditions improve. University of Houston microbiologists found that this organism, isolated from a spacecraft clean room, could sit in this suspended animation long enough to fool standard tests that would normally certify a surface as sterile.

That behavior lines up with broader work showing that bacteria in spacecraft clean rooms can go dormant, evading death and standard monitoring. Experiments described in one study showed that when these microbes were exposed to intense stress, the number of viable cells appeared to plummet within days, yet a fraction of the population persisted in a hard-to-detect state and later recovered. For planetary protection, this is a nightmare scenario: a bug that looks dead on Earth, passes inspection, then wakes up on another planet where liquid water or nutrients are available. If such a bug hitched a ride to another planet, it could wake up upon arrival and potentially disrupt existing extraterrestrial ecosystems or confuse future life detection experiments.

Not-so-clean rooms and the limits of sterilization

All of this forces me to rethink what the phrase “cleanroom” really means. Not and other Scientists who sampled NASA spacecraft facilities found that these environments, while far cleaner than a typical lab or hospital, are not devoid of life. Instead, they host a curated set of survivors that have endured repeated rounds of chemical and physical assault. These hardy microbes may also be able to tolerate conditions that mimic parts of the Martian surface, including low nutrients and desiccation, which makes them particularly concerning as potential stowaways.

In that light, the label “not-so-clean rooms” is less a criticism of NASA and more a recognition that absolute sterility is practically impossible at the scale of an entire spacecraft assembly building. Filters can remove particles down to a certain size, disinfectants can kill most cells, and human access can be tightly controlled, yet the discovery of 26 new microbe species in a single facility shows that life finds a way to persist. For me, the key lesson is that planetary protection cannot rely solely on counting colony-forming units on a petri dish. It has to account for dormant cells, extremotolerant genomes and the possibility that some organisms will always slip through.

Why planetary protection suddenly feels more urgent

Planetary protection has always been a balancing act between scientific ambition and biological caution, but the cleanroom discoveries tilt that balance toward greater urgency. If 26 previously unknown species can thrive in the most controlled parts of a NASA facility, then the risk that at least one of them could reach Mars or another target world is not hypothetical. The fact that Many of these species possess genes that make them resilient to decontamination and radiation means they are exactly the types of organisms most likely to survive launch, cruise and landing.

That matters because future missions are explicitly designed to look for subtle signs of life, from organic molecules in Martian regolith to potential biosignatures in the icy plumes of moons like Europa or Enceladus. A single extremotolerant bacterium that wakes up in the wrong place could produce signals that mimic indigenous life or, in a worst case, outcompete a fragile native ecosystem. When I listen to discussions in venues like the Vond podcast, where scientists talk through the implications of space-hardy bacteria in spacecraft environments, I hear a growing consensus that planetary protection protocols must evolve as quickly as the microbes they are trying to contain.

Space as a new microbial frontier

There is another side to this story that I find both unsettling and scientifically thrilling. The same traits that make these bacteria a contamination risk also make them valuable tools for understanding how life copes with space. In conversations and outreach pieces, researchers have described experiments in which bacteria were exposed to the vacuum and radiation of orbit, only to be recovered alive. A recent discussion framed as Bacteria Found Surviving in Space! Could It Threaten Future exploration highlights how some of these organisms, including cleanroom isolates, can endure conditions that would kill most known life.

Those results suggest that space is not an absolute barrier to microbial survival, at least over mission timescales. If a bacterium from a NASA cleanroom can cling to a spacecraft surface, ride a launch, and then survive in orbit or on another world, it becomes a living probe of life’s limits. That is scientifically fascinating, but it also sharpens the ethical questions around forward contamination. I find myself weighing the potential insights from studying such extremophiles against the responsibility to keep other worlds as untouched as possible until we know what, if anything, lives there already.

Rethinking how we build and certify spacecraft

Given what we now know about the microbial residents of NASA cleanrooms, the traditional approach to spacecraft sterilization looks increasingly incomplete. Counting surface microbes after a cleaning cycle and comparing the result to a numerical threshold made sense when we assumed that most contaminants were easy to kill and easy to detect. The discovery that some cleanroom bacteria can Plays Dead to Survive, entering dormancy that fools standard assays, means that a “pass” on a cleanliness test may not guarantee the absence of viable life.

Engineers and microbiologists are already exploring new strategies in response. Some of the genomic work on the 215 Phoenix-era isolates and the 26 novel species suggests that targeting specific resistance pathways, rather than applying broad-spectrum disinfectants, could be more effective. Others argue for redesigning hardware so that the most sensitive components are assembled in even more restricted environments, or for adding in situ biosensors that can detect microbial activity over time instead of relying on one-off swabs. When I look across the technical discussions and the public-facing explanations, from detailed genomic studies to accessible breakdowns on platforms like Jul podcast episodes, I see a field that is rapidly updating its playbook in light of the cleanroom surprise.

The uneasy future of “clean” exploration

For all the technical nuance, the core tension is simple. Humanity wants to explore, sample and eventually inhabit other worlds, yet we carry with us a microbiome that is both resilient and poorly mapped. The revelation that 26 never-before-seen bacteria were thriving in NASA cleanrooms, that extreme microbes surrounded a Mars-bound robot, and that at least one Rare Bacterium can effectively Plays Dead to Survive, forces me to admit that we are not as in control of our microbial footprint as we once believed. The cleanroom, once a symbol of sterility, now looks more like a training ground where the toughest microbes prepare for interplanetary travel.

That does not mean exploration should stop. It does mean that every mission, from a simple orbiter to a sample return, has to grapple with the reality that life is more adaptable than our protocols anticipated. As I weigh the evidence from genomic surveys, dormancy experiments and space exposure tests, I come away convinced that the next era of planetary protection will be defined less by the quest for perfect sterility and more by a nuanced understanding of microbial ecology. The 26 new bacteria from NASA’s cleanrooms are not just a curiosity, they are a warning that in the contest between human engineering and microbial evolution, the microbes are always closer behind us than we think.

More from MorningOverview