For decades, crewed missions to Mars have been framed as a distant dream, but planetary scientists are now converging on a specific region that could finally turn that ambition into a practical flight plan. New analyses of orbital data point to a mid‑latitude zone where buried ice, gentle terrain and favorable sunlight come together in a way that no other known site on the Red Planet can match. If current assessments hold up, the first human footprints on Mars are likely to be pressed into this landscape.

Instead of treating Mars as a blank canvas, researchers are now treating it like real estate, weighing trade‑offs between safety, resources and long‑term livability. The emerging favorite is Amazonis Planitia, a broad volcanic plain that appears to hide shallow water ice beneath its surface, offering both a safe runway for landing and the raw materials for a self‑sustaining outpost. I see this shift as the moment when Mars exploration stops being an abstract goal and starts to look like site selection for a frontier town.

Why a “best” landing site matters more than ever

Choosing a single primary destination for the first crewed mission is not just a symbolic decision, it is a hard constraint on everything from rocket design to how astronauts will survive their first night on Mars. A site that combines accessible water, stable temperatures and flat ground can drastically reduce the mass that needs to be launched from Earth, because crews can rely on local materials instead of hauling every kilogram of air, water and fuel across interplanetary space. In practical terms, the right patch of Martian ground could shave years off the timeline for a permanent base by making it easier to scale up from a landing zone to a functioning settlement.

Many experts have envisioned people living on Mars by building a self‑sustaining city that grows outward from an initial beachhead, but they also stress that this vision collapses if the first crews are forced to operate in a hostile, resource‑poor environment. That is why recent work highlighting a relatively smooth, flat terrain with minimal obstacles, combined with buried ice that can be tapped with modest equipment, has attracted so much attention among mission planners. The argument is that a location with these characteristics, described in detail in analyses of promising Martian terrain, does not just make landing safer, it makes long‑term habitation technically and economically plausible.

Amazonis Planitia steps into the spotlight

Among the many candidate regions that have been discussed over the years, Amazonis Planitia has recently emerged as a front‑runner because it sits in Mars’ mid‑latitudes, where conditions strike a balance between polar cold and equatorial heat. This broad plain appears to offer large expanses of relatively level ground, which is crucial for landing heavy spacecraft and for later building out infrastructure such as habitats, power systems and landing pads. From an engineering standpoint, a flat, obstacle‑free approach corridor can dramatically reduce the risk of a catastrophic touchdown and simplify the design of descent and landing systems.

What elevates Amazonis Planitia from a safe parking lot to a serious colonization candidate is the evidence that it contains accessible water ice close to the surface. Reporting on how scientists identify a human landing site on Mars highlights that Amazonis Planitia is considered a prime candidate for future missions precisely because it combines mid‑latitude sunlight with this shallow ice, which can be reached with relatively simple drilling or excavation gear. The same work notes that accessible water ice is significantly more valuable than deeply buried deposits, because it can be converted into drinking water, breathable oxygen and rocket propellant without constant back and forth to Earth for resupply, a point underscored in assessments of Amazonis Planitia on Mars.

Shallow ice as the foundation of a Martian economy

The real breakthrough in recent studies is not just that there is ice on Mars, which has been known for years, but that some of it appears to lie just beneath the surface in regions that are otherwise friendly to human operations. Shallow water ice can be reached with relatively lightweight drills or even mechanical scoops, which means early missions do not need to bring industrial‑scale mining equipment. This transforms ice from a scientific curiosity into a practical resource that can underpin life support systems and fuel production from the first expedition onward.

Scientists have identified shallow water ice in a mid‑latitude zone that balances sunlight, temperature and accessibility, and they argue that this combination makes it a strong candidate for where humanity will take its first footsteps on another planet. Analyses of this hidden ice emphasize that the deposits are close enough to the surface to be tapped repeatedly without exhausting them quickly, and that the surrounding environment is stable enough for long‑term operations. These findings, described in detail in work on hidden ice on Mars, are what allow mission designers to start sketching out realistic in situ resource utilization chains instead of hypothetical ones.

In situ resource utilization moves from theory to site plan

For years, in situ resource utilization has been a buzz phrase in Mars architecture studies, but it often sat in the background as a theoretical advantage rather than a concrete design driver. That is now changing as specific locations are tied to specific resource maps, especially for water ice that can be turned into hydrogen and oxygen through electrolysis. Once a site is known to contain ice within a few meters of the surface, engineers can size power systems, processing plants and storage tanks with much greater confidence, because they are no longer guessing about how much material they can actually extract.

Recent reporting on how scientists may have found the best place for humans to land on Mars explains that this approach, known as in situ resource utilization, allows explorers to use materials already available on another planet instead of hauling everything from Earth. The same work notes that ice just beneath the Martian surface can be converted into water, oxygen and fuel, effectively turning the landing site into a refueling depot for return trips or further exploration. By tying these concepts directly to a specific region with confirmed subsurface ice, as detailed in analyses of ice just beneath the Martian surface, planners can finally move from generic ISRU diagrams to site‑specific engineering.

Balancing sunlight, temperature and safety

Even with abundant ice, a landing site will fail if it exposes crews to extreme cold or leaves them starved for solar power. That is why the mid‑latitude setting of Amazonis Planitia is so important: it offers more moderate temperatures than the poles and more manageable dust conditions than some equatorial regions, while still providing enough sunlight to power solar arrays. This balance reduces the burden on nuclear or other backup power sources and makes it easier to keep habitats within a survivable temperature range without excessive insulation or heating.

Studies of shallow ice on Mars emphasize that the most promising region is one that balances sunlight, temperature and accessibility, rather than maximizing any single factor at the expense of the others. The same analyses point out that hidden ice beneath Mars’ surface in this zone may mark the spot where humanity first sets foot on the Red Planet, precisely because it combines environmental safety with resource abundance. By highlighting how hidden ice beneath Mars’ surface lies just below the Martian surface in a region that still receives ample sunlight, work on hidden ice beneath Mars’ surface helps explain why this particular patch of ground is rising above other candidates.

How Amazonis compares with other favorite regions

Amazonis Planitia is not the only place that has been floated as a future Martian hub, and comparing it with other popular suggestions helps clarify what is at stake in the current debate. Enthusiasts and some researchers have long championed areas like Arcadia Planitia and Hellas Planitia, each with its own mix of advantages and drawbacks. Arcadia Planitia, for example, has been praised for its potential ice deposits and relatively smooth terrain, while Hellas Planitia, sometimes described as a Southern Hub, offers the benefits of a deep basin that could provide additional atmospheric shielding and potentially milder surface conditions.

Community discussions about the first Martian colony often highlight that Hellas Planitia is one of the DEEPEST asteroid impact craters in the ENTIRE solar system, with outer rims that tower above the basin floor, and that Arcadia Planitia would be the ideal place for a first base that could eventually turn into a capital city. These arguments, captured in detailed debates over the first Martian colony, show that there is no shortage of imaginative thinking about where humans might settle. What sets Amazonis Planitia apart in the current scientific literature, however, is the combination of confirmed shallow ice, mid‑latitude sunlight and a large, flat expanse that appears particularly well suited to the first high‑risk landing of a crewed vehicle.

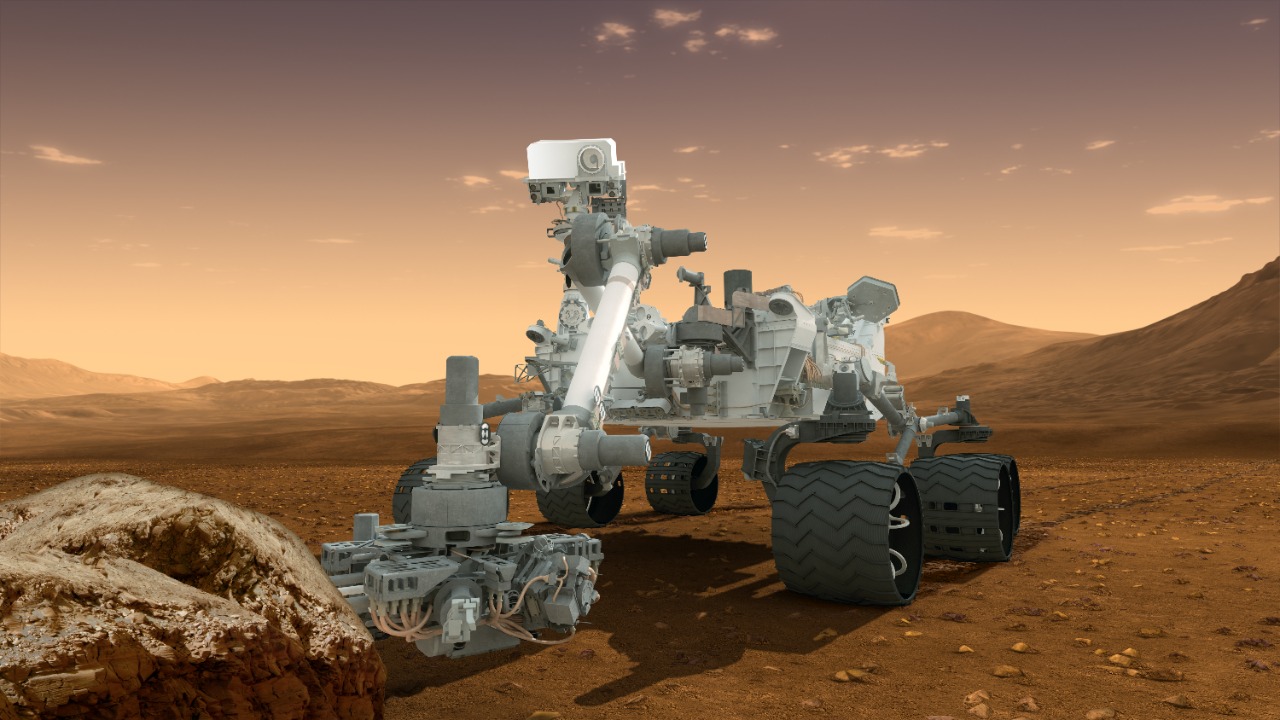

From concept art to concrete mission design

The identification of a specific, resource‑rich landing zone is already changing how agencies and companies talk about Mars missions. Instead of generic depictions of astronauts wandering a random red landscape, mission concepts are starting to reference particular plains and basins, with trajectories and entry profiles tailored to their coordinates. This shift mirrors the way Apollo missions moved from vague talk of “going to the Moon” to detailed planning around the Sea of Tranquility, where terrain maps and lighting conditions shaped every aspect of the landing sequence.

Analyses of how landing on Mars just got real describe this moment as a major step forward in turning Mars colonization from concept to concrete planning, because a preferred site allows engineers to optimize everything from heat shields to communication links. Once a region like Amazonis Planitia is treated as the default target, simulations can incorporate its specific elevation, dust environment and thermal properties, leading to more realistic risk assessments and hardware designs. The recognition that a particular plain on Mars can serve as the perfect site for astronauts, as discussed in work on landing on Mars, is what allows mission design to finally lock onto a real destination instead of an abstract world.

The science behind finding buried ice

None of this site selection work would be possible without sophisticated remote sensing techniques that can infer what lies beneath the Martian surface. Radar instruments on orbiters send pulses into the ground and measure the reflections, while neutron detectors and thermal imagers provide additional clues about the presence of hydrogen and how quickly the soil heats and cools. By combining these data sets, scientists can distinguish between dry regolith, rock and ice, and can estimate how deep the ice lies and how pure it is.

Researchers affiliated with the University of Mississippi have played a role in refining these methods, emphasizing that before humans can make the long trip to another world, scientists must identify a safe and resource‑rich landing site. Their work highlights that shallow ice deposits can be accessed more easily than deeply buried deposits, which would require heavy drilling rigs and far more energy. This focus on accessible ice, described in analyses of how scientists identify an ideal Mars landing site, is what underpins the current enthusiasm for Amazonis Planitia and similar mid‑latitude plains.

What a first base at Amazonis Planitia might look like

With a likely site in view, it becomes easier to imagine the layout and daily rhythms of a first human base on Mars. A landing zone on Amazonis Planitia would probably feature a cluster of pressurized habitats connected by short, covered walkways, with solar arrays fanning out across the flat terrain and a dedicated area for ice extraction and processing. The shallow ice would be mined and piped into a central plant where it could be split into oxygen and hydrogen, stored in tanks and fed into life support systems and fuel cells, turning the base into a small industrial complex as much as a research station.

Because the terrain is relatively smooth, heavy rovers and construction equipment could move between modules without the constant risk of tipping or getting trapped in boulder fields, which would accelerate the build‑out of additional structures such as greenhouses and radiation‑shielded shelters. Over time, the base could expand into a small settlement, with landing pads hardened to reduce dust, storage depots for spare parts and perhaps even underground living quarters carved into the regolith for extra protection. The vision of Many experts who see people living on Mars in a self‑sustaining city, supported by a flat terrain with minimal obstacles and abundant local resources, aligns closely with what current analyses suggest is possible at Amazonis Planitia, as described in work on a promising landing site on Mars.

More from MorningOverview