The Sun’s magnetic field is invisible to our eyes, but it quietly shapes everything from the shimmering auroras over the poles to the reliability of GPS on a jet’s navigation screen. When that magnetic engine surges, it can light up the sky with color, but it can also knock out power grids and disrupt communications across continents. Understanding how this field works is no longer an abstract astrophysics problem, it is a practical question about how a technological civilization lives with a restless star.

At its core, the story is simple: the Sun is a giant ball of electrically charged gas, and moving electric charges create magnetic fields. The details are anything but simple. The Sun’s magnetism twists, tangles, and flips in a roughly 11‑year rhythm, driving solar storms that can buffet Earth and every spacecraft we send into its path. I want to unpack what scientists know about this magnetic field, how it behaves, and why its moods matter so much to life and infrastructure on Earth.

Magnetism is the key to understanding the Sun

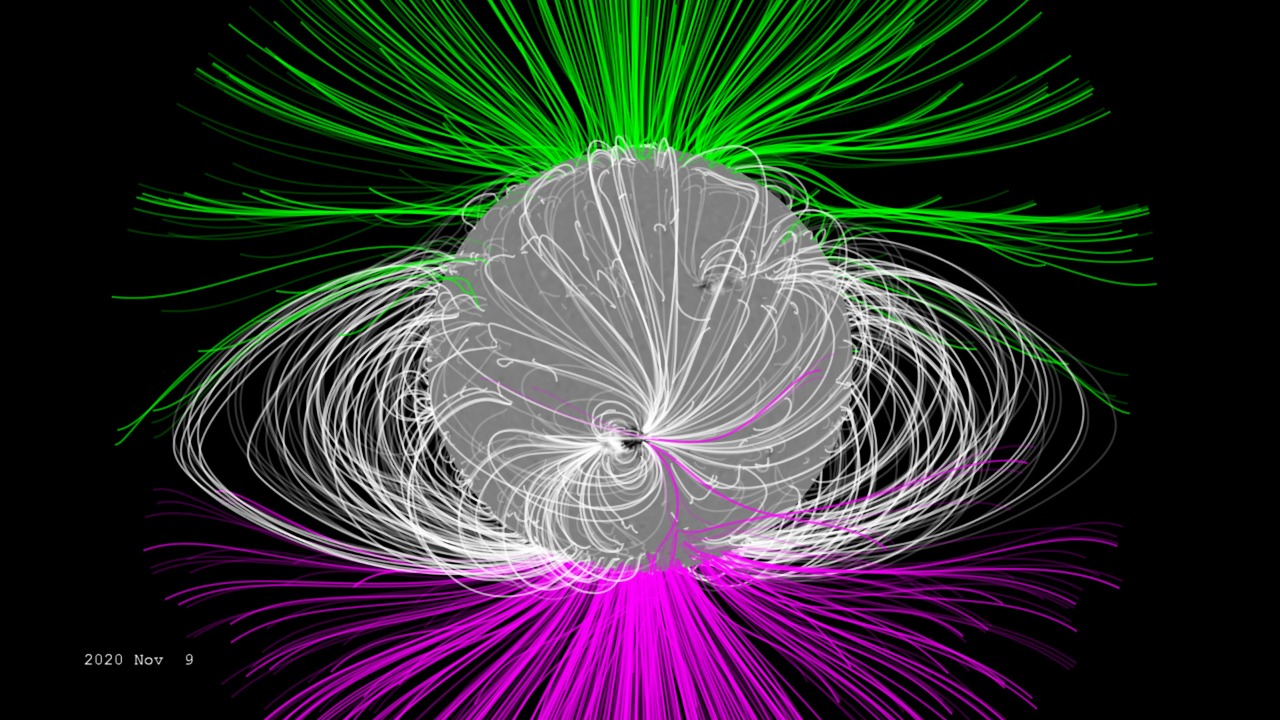

When physicists say that magnetism is the key to understanding the Sun, they are not being poetic, they are being literal. Without its magnetic field, the Sun would be a relatively smooth, featureless ball of hot gas, radiating steadily and changing only slowly over billions of years. Instead, magnetic forces sculpt dark sunspots, power explosive flares, and shape the vast corona that stretches far beyond the visible surface, so the Sun’s behavior over days to decades is really a story about how its magnetic field evolves. Researchers emphasize that magnetism is the key to everything from the smallest loops of plasma to the global structure of the corona.

At the most basic level, the Sun’s magnetic field is generated by moving, electrically conducting fluid inside the star. Deep beneath the surface, hot plasma circulates and rotates, and those motions act like a dynamo, turning kinetic energy into magnetic energy. The result is a large‑scale field that threads through the Sun and out into space, but it is not a simple bar magnet. Instead, the field is tangled and dynamic, with regions where the lines of force are tightly bundled and others where they fan out into the solar wind. As the Sun spins and its plasma churns, those magnetic lines are dragged, twisted, and sometimes snapped and reconnected, releasing bursts of energy that we see as flares and eruptions.

How the Sun’s magnetic field is built inside

To understand why the Sun’s magnetism is so complex, I start with its interior. The Sun is made of dense, electrically charged gas, and in the outer third of its radius that gas is in constant convective motion, with hot material rising and cooler material sinking. Because the Sun rotates faster at the equator than at the poles, this differential rotation stretches and shears magnetic field lines embedded in the plasma. Over time, those motions amplify and reorganize the field, a process scientists describe as a magnetic dynamo. The basic picture is that conductive fluids inside The Sun generate and sustain the Magnetic Field that later drives visible activity at the surface.

On top of this global dynamo, smaller scale flows and turbulence create local magnetic structures that can be far stronger than the average field. In active regions, the field can reach thousands of gauss, vastly exceeding the strength of Earth’s surface field, which is less than 1 gauss. These intense patches of magnetism punch through the visible surface, suppressing convection and cooling the gas, which is why sunspots appear dark. The same regions store enormous magnetic energy in twisted loops of plasma, and when those loops reconnect, they can unleash solar flares and coronal mass ejections that hurl charged particles into space. The Sun’s interior motions, in other words, constantly pump energy into a magnetic system that is primed to snap.

The Solar Cycle and the Sun’s changing personality

One of the most striking features of the Sun’s magnetism is that it waxes and wanes in a regular rhythm known as The Solar Cycle. Over roughly 11 years, the number of sunspots rises from a quiet minimum to a busy maximum and then falls again, reflecting how the global magnetic field is being wound up and then reorganized. Much of the Sun’s changing personality in this cycle comes from its core and convective layers, where dense, electrically charged gas and circulating currents of plasma reshape the field over time. Educational material on what the solar cycle is highlights how this ebb and flow of magnetism drives the Sun’s “tempestuous nature.”

As the cycle progresses toward its peak, the magnetic field becomes more tangled, and the surface bristles with active regions. Solar flares happen because of this magnetic complexity, and they are most common when the Sun is in the maximum part of its cycle, when the field is strongest and most distorted. During these years, the Sun is more likely to produce large eruptions that can affect Earth, while during solar minimum the field is more orderly and activity is subdued. For forecasters and satellite operators, tracking where we are in this cycle is essential, because it sets the background risk level for space weather that can affect everything from radio communications to astronaut safety.

From sunspots to storms: how magnetism erupts

On the surface, the Sun’s magnetic field reveals itself through sunspots, bright loops, and sudden flashes of radiation. Sunspots mark places where strong magnetic fields pierce the photosphere, and they often come in pairs or groups with opposite magnetic polarity. Above them, arches of glowing plasma trace the invisible field lines, forming prominences and coronal loops. When those loops become too twisted or stressed, they can suddenly rearrange in a process called magnetic reconnection, converting stored magnetic energy into heat, light, and kinetic energy. That is the trigger for solar flares and for the massive clouds of plasma known as coronal mass ejections that can race outward at millions of kilometers per hour.

These eruptions are not random fireworks, they are the direct consequence of how the solar magnetic field evolves. As the field changes over the cycle, the number and complexity of active regions rise and fall, and with them the rate of flares and eruptions. Research on the solar magnetic field notes that active regions can host field strengths of thousands of gauss, far stronger than Earth’s, and that such intense magnetism is what powers the most energetic events. When those events are aimed toward Earth, they can compress our own magnetic field, inject energy into the upper atmosphere, and trigger geomagnetic storms that ripple through power lines and communication systems.

A field that flips: the 11‑year magnetic reversal

One of the most counterintuitive aspects of the Sun’s magnetism is that the global field actually reverses polarity roughly every 11 years. In other words, the magnetic north and south poles of the Sun swap places, so a full magnetic cycle takes about 22 years. This flip is tied to the same dynamo processes that generate the field in the first place, as differential rotation and convection gradually twist the field until it becomes unstable and reorganizes. During the reversal, the large‑scale field weakens and becomes more complex, even as the number of sunspots and active regions reaches a peak.

Detailed studies of the changing solar magnetic field show that as the cycle moves past maximum, the global field gradually strengthens again in its new orientation while sunspot numbers decline. This interplay between the large‑scale field and smaller active regions helps explain why solar activity is not perfectly periodic and why some cycles are stronger than others. For Earth, the polarity of the Sun’s field matters because it affects how the solar wind interacts with our own magnetosphere, influencing the shape of the heliospheric current sheet and the way charged particles are funneled into the planetary environment.

How the Sun’s magnetism reaches Earth

The Sun’s magnetic field does not stop at the visible surface, it permeates the solar atmosphere and extends outward with the solar wind. The Sun’s average large‑scale magnetic field threads through the photosphere, the chromosphere, and the corona, and then is carried into interplanetary space by streams of charged particles. As a result, the entire solar system is embedded in a vast magnetic bubble shaped by The Sun, and Earth orbits within this magnetized flow. Educational material on How the Sun affects space around it emphasizes that this field connects the Earth to the Sun along invisible lines of force.

Closer to home, the Sun’s magnetic field interacts directly with Earth’s own magnetosphere. The Sun’s magnetic field permeates its atmosphere and the solar wind, and when that wind reaches Earth, it can reconnect with our planet’s field, transferring energy and particles into the near‑Earth environment. This interaction drives auroras, disturbs satellite orbits by heating the upper atmosphere, and can induce currents in long conductors on the ground. Observers have documented how The Sun’s magnetic field can alter the orbits of satellites and disrupt radio communications when geomagnetic storms are strong.

Earth’s magnetic shield and the Mars warning

Earth is not a passive target in this magnetic drama, it has its own field that acts as a shield. Generated by motions in the planet’s liquid outer core, Earth’s magnetism deflects much of the solar wind and channels charged particles toward the poles, where they create auroras instead of stripping away the atmosphere. Without this protection, the constant flow of energetic particles from the Sun would erode the upper atmosphere over time, making it harder for the planet to hold on to its air and water. Studies of the Magnetic fields of planets highlight that Earth’s field helps the planet hold on to its oceans and that if a planet ever loses its magnetic field, it can end up looking more like Mars.

Mars is the cautionary tale. The Red Planet once had liquid water on its surface, but it lacks a strong global magnetic field today. Without that shield, the solar wind has had billions of years to strip away much of Mars’s atmosphere, leaving it cold, dry, and exposed. The comparison underscores why Earth’s field is so crucial in the context of the Sun’s magnetism. When solar storms intensify, our magnetosphere flexes and sometimes cracks, but it still absorbs much of the impact. If that field were to weaken significantly, the same solar activity that now produces beautiful auroras could become a long‑term threat to the stability of our climate and oceans.

When the Sun gets dangerous: space weather and superstorms

Most days, the Sun’s magnetic field affects Earth in subtle ways, but during major eruptions it can become a direct hazard to modern infrastructure. When a large coronal mass ejection is aimed at Earth, the embedded magnetic field can reconnect with our own, driving a geomagnetic storm that disturbs the ionosphere and induces currents in power grids and pipelines. Historical records show that in 1859, a large solar storm known as the Carrington Event caused widespread telegraph system failures, and in 1989, a coronal mass ejection triggered a blackout in Quebec while creating dazzling aurora light shows far from the poles. Accounts of Earth’s magnetic field emphasize how these storms can reshape society’s relationship with technology.

In recent years, researchers have warned that a truly extreme solar superstorm could have far more serious consequences. New USGS work on 5 Geomagnetic Storms that reshaped society describes how intense solar activity and large geomagnetic storms could impact much of the United States, stressing long‑distance power lines and critical infrastructure. Another analysis of what a solar superstorm could mean for the US notes that such an event could disrupt communications, navigation, and even undersea cables that carry internet traffic between continents. The same magnetic processes that make the Sun beautiful and dynamic, in other words, can also threaten the systems that keep a modern economy running.

Why scientists chase the “magnetic Sun”

Given these stakes, it is no surprise that scientists have made the Sun’s magnetism a central focus of heliophysics. Researchers describe the solar magnetic system as the driver of the approximately 11‑year activity cycle on the Sun, and they are working to get a handle on what processes inside the star create the Sun’s magnetic fields in the first place. Missions and models that probe the interior, the surface, and the corona are all aimed at understanding this “magnetic Sun” well enough to predict its behavior. A detailed overview of understanding the magnetic Sun underscores how central this problem is to forecasting solar activity.

At the same time, space weather specialists are refining models that link the Sun’s magnetic field to conditions at Earth. They track how the field evolves over the solar cycle, how it shapes the solar wind, and how eruptions propagate through interplanetary space. Educational resources on Solar flares and the solar cycle help translate this science into practical guidance for operators of satellites, airlines, and power grids. The goal is not to control the Sun, which is impossible, but to live with its magnetic moods by anticipating when they will pose the greatest risk.

The Sun’s magnetic field and everyday life

For most people, the Sun’s magnetic field only becomes visible when it paints the sky with auroras or interrupts a favorite streaming service. Yet its influence is woven into daily life in quieter ways. GPS signals that guide ride‑share drivers and container ships pass through the ionosphere, which is shaped by solar magnetism. High‑frequency radio used by aircraft on polar routes can fade during geomagnetic storms, forcing rerouting and delays. Even the accuracy of timing signals that underpin financial transactions can be affected when the upper atmosphere is disturbed by solar activity linked to the field of the global corona, a connection highlighted in discussions of space weather and the Sun’s magnetic fields.

Looking ahead, the dependence of modern society on space‑based systems only deepens the importance of understanding the Sun’s magnetism. As more satellites crowd low Earth orbit and as new technologies like autonomous shipping and precision agriculture lean on uninterrupted navigation and communication, the cost of underestimating a solar storm grows. The Sun’s magnetic field may seem like a distant astrophysical curiosity, but in practice it is a moving part of the same system that keeps lights on, planes flying, and data flowing. Learning to read that field, and to respect its power, is part of the price of living in the glow of a star.

More from MorningOverview