Physicists are quietly rolling out a new generation of simulation codes that promise to do more than crunch numbers. By weaving together quantum theory, astrophysical data and high precision sensors, these tools are being designed to tease out how dark matter actually behaves, not just how much of it there is. If they work, they could turn a century of inference into something closer to direct scrutiny of the invisible scaffolding of the cosmos.

Instead of treating dark matter as a static background, the emerging software frameworks model it as a dynamic player that co-evolves with galaxies, black holes and even quantum fields in the lab. I see this shift as a move from bookkeeping to storytelling, where the code is built to test specific narratives about what dark matter is made of and how it interacts, then confront those stories with data from telescopes, interferometers and particle detectors.

The century‑long puzzle that demands better code

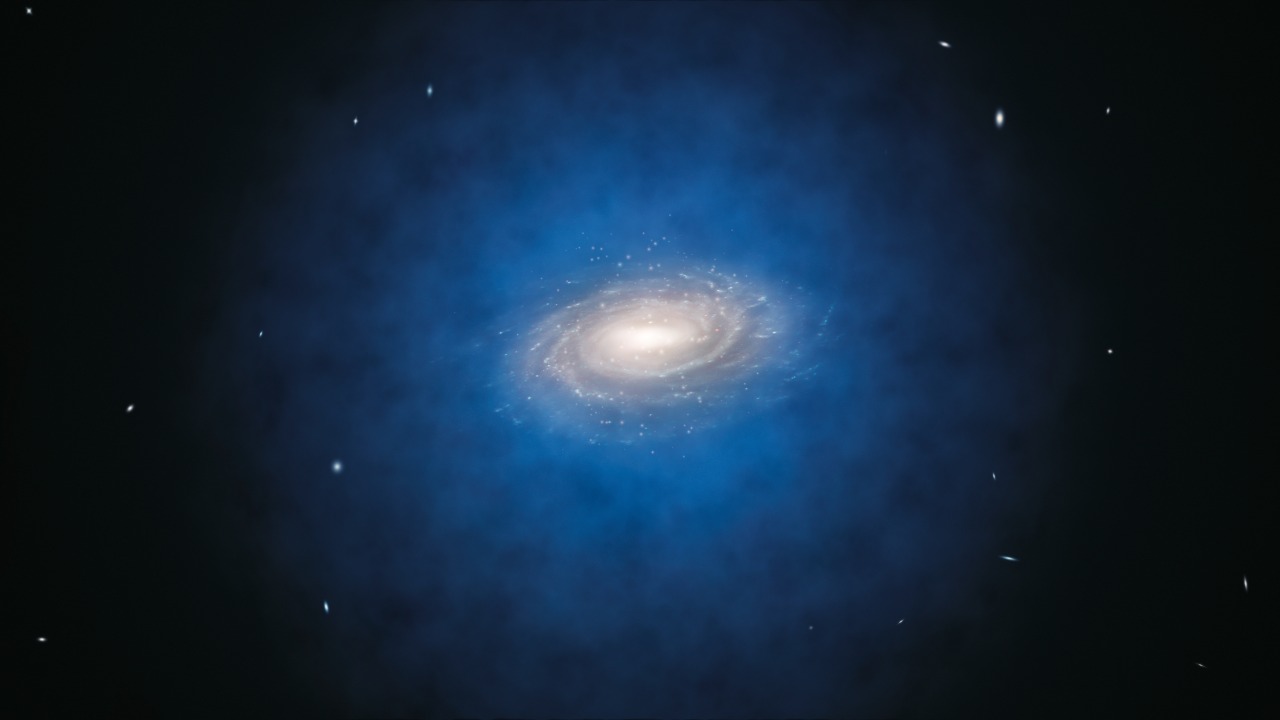

Nearly a century after astronomers first invoked dark matter to explain the strange motions of galaxies, the basic mystery has not gone away. Gravity still points to a huge reservoir of unseen mass, and recent work argues that scientists may finally have found signatures of this material after that long search, tying the invisible component directly to the structure of galaxy halos and the motions of stars that orbit within them. The claim that dark matter could at last be emerging from the noise raises the stakes for any new physics code that aims to model its behavior, because the software will be judged against increasingly specific observational hints rather than abstract theory alone, as highlighted by research that notes how Nearly a century of work is converging on the universe’s invisible mass.

At the same time, cosmologists now treat dark matter as the dominant ingredient of the cosmic recipe, with one influential line of work stating that this mysterious substance accounts for 80% of all matter in the universe. That same research, rooted in Jul discussions of mirror worlds and alternative sectors, leans on the discipline of Science to argue that dark matter might obey the same fundamental laws as the known universe while remaining hidden from direct view. Any code that claims to expose dark matter’s hidden behavior has to be able to reproduce this global 80% budget, then drill down to the level of individual galaxies and clusters without breaking the successful large scale picture.

From static halos to co‑evolving universes

For decades, simulations treated dark matter as a cold, collisionless fluid that simply provided a gravitational backbone for galaxy formation. That picture is starting to look too simple, and new models of the Big Bang developed by Northeastern physicists instead show that the visible universe and invisible dark matter co-evolved, with each component shaping the other from the earliest instants onward. In that framework, the code must track how density ripples in the dark sector feed into the growth of ordinary matter, and how feedback from stars and black holes can in turn sculpt the dark distribution, a feedback loop captured in New models of the Big Bang by Northeastern researchers that emphasize how Mat calculations link the two sectors.

That co-evolutionary view is not just philosophical, it has concrete implications for how code is structured. Instead of bolting dark matter on as a fixed halo, the new generation of simulations must solve coupled equations for both visible and invisible components, often across billions of light years and billions of years of cosmic time. The payoff is that such models can be directly compared with high precision sky surveys and gravitational lensing maps, allowing developers to tune their algorithms until the simulated universe and the observed one line up in detail, rather than only matching a few bulk statistics.

Quantum tools and ultralight fields in the lab

While cosmological simulations tackle the largest scales, another front in the code revolution is unfolding in quantum laboratories that hunt for ultralight dark matter fields. One influential program of work argues that transformative advances in quantum technologies have produced a new class of high precision quantum sensors that can respond to scalar and vector ultralight dark matter, treating the dark component as an oscillating classical, largely coherent field that washes through the lab. In that picture, the software must model how such a field would imprint tiny, time varying signals on the sensor output, a task described in detail in Transformative discussions of scalar and vector ultralight dark matter that treat the sensor as part of the physics, not just a passive recorder.

Another laboratory effort, known as QROCODILE, pushes sensitivity to dark matter related effects at temperatures near absolute zero, where thermal noise is minimized and quantum behavior dominates. Reporting on this project notes that QROCODILE has set record breaking sensitivity benchmarks and is explicitly framed as a tool to probe one of the greatest mysteries in physics, with the work anchored at The Hebrew University of Jerusalem and described with formal markers like Date and Source to emphasize its experimental pedigree. To interpret such delicate measurements, researchers rely on code that can simulate both the quantum device and hypothetical dark matter couplings, a need underscored by descriptions of how QROCODILE is being positioned as a bridge between theory and experiment.

New physics code built on open quantum solvers

The most ambitious dark matter codes do not start from scratch, they build on a growing ecosystem of open source solvers for quantum and electromagnetic dynamics. One prominent example is CoOMBE, a suite of programs for integrating the optical Bloch equations and Maxwell Bloch equations in various approximations, which its authors explicitly compare with other general purpose tools for related calculations. By providing a flexible framework for solving the Maxwell Bloch equations in different regimes, CoOMBE gives dark matter theorists a ready made engine for modeling how exotic fields might interact with atoms, photons and cavities, as described in the technical overview that notes how a number of open source programs already tackle similar problems.

In parallel, other theorists have proposed new ways to search for dark matter particles by focusing on how they might interact with the electrons in atoms, rather than only with nuclei or through gravitational effects. One influential paper describes how such interactions could reveal hidden materials properties, effectively turning condensed matter systems into dark matter detectors, and explicitly ties the work to a publication in August 2020 in Physical Review Research. The code that underpins this approach has to handle both the quantum many body problem and the speculative dark sector couplings, a dual challenge that is captured in the description of a new way to search for dark matter particles that reveals hidden materials properties.

Gravitational waves, gamma rays and the multi‑messenger test

Any claim that new code can expose dark matter’s hidden behavior will ultimately be tested against a flood of data from across the spectrum, and gravitational waves are rapidly joining that mix. Quantum physics reporting now lists as one of its Top Headlines a study that argues gravitational waves may reveal hidden dark matter around black holes, treating the ripples in spacetime as probes of the invisible halos that surround compact objects. That work, which appears under the banner of Gravitational Waves May Reveal Hidden Dark Matter Around Black Holes, sits alongside other Gravitational topics in curated quantum physics coverage and signals that waveform modeling codes must now include dark matter effects if they want to keep up with the data.

High energy photons provide a complementary window, and the Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope has been scanning the sky for more than a decade in search of unexplained gamma ray excesses that could hint at dark matter annihilation or decay. The mission’s science support center describes how its instruments map the gamma ray sky and provide open access to data for the community, effectively turning Fermi into a testbed for any code that predicts specific spectral or spatial signatures. When developers claim their simulations can predict a dark matter signal, they are implicitly inviting comparison with the catalogs and analysis tools hosted at the Fermi site, where gamma ray maps can either validate or rule out entire classes of models.

Telescopes and interferometers feed the simulations

On the optical and infrared side, the James Webb Space Telescope is already reshaping how cosmologists think about the early universe, and some teams are explicitly using it to probe dark matter. One group led by Windhorst and collaborators has looked at simulations of the universe that include different types of dark matter, then compared those virtual universes with Webb’s deep images to see which scenarios best match the observed distribution of galaxies. Their approach, which leans heavily on simulation as a research method, is described in detail in work that notes how Windhorst and colleagues used simulation to investigate how Webb could illuminate dark matter in a way scientists did not initially anticipate.

Closer to home, atom interferometers are being reimagined as dark matter detectors, with new tools that self correct for imperfections in the light used to manipulate atoms. One such device, developed at the Center for Fundamental Physics, is described as overcoming limitations that plagued earlier interferometers, with the key improvement summarized in a report that begins with the word But to emphasize the contrast with previous designs. For code developers, these instruments provide a new class of data streams that must be modeled from first principles, a challenge captured in the description of how But unlike other atom interferometers, the new tool self corrects and is explicitly aimed at probing the embarrassing problem of dark matter.

Signals, candidates and the WIMP revival

Even as ultralight fields and mirror worlds gain attention, more traditional candidates like WIMPs are not going quietly. A recent study in the Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics leans on the WIMP hypothesis and uses data from NAS instruments to argue that astronomers may have detected dark matter for the first time, focusing on how particles in a galactic halo could produce specific signals. The analysis, which treats the WIMP as a benchmark model, is summarized in coverage that explains how a Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics paper uses the WIMP framework and NAS data to interpret a potential detection from the dark matter halo.

Other observations are challenging long held assumptions about how dark matter behaves on galactic scales. One widely discussed set of results, highlighted in a Jul video presentation, points out that astrophysicists have often assumed dark matter is not just dark but also passes through normal matter without doing much, and then presents strange new observations that suggest this picture may be incomplete. The argument is that if dark matter interacts more strongly than expected in some environments, then the simulations that treat it as perfectly collisionless will miss key features, a tension that is dramatized in the Jul discussion of strange new observations that reveal a major clue about dark matter.

AI, citizen coders and the risks of democratized dark matter tools

The sophistication of these new physics codes is colliding with a broader trend in software, where advanced tools are becoming accessible to non specialists. Commentators on data science have noted that second, new tools and advances in the data space allow teams to self serve analytics, and that finally, advanced models once reserved for experts are now available to a wider pool of users without requiring deep understanding of the underlying math. That shift, described in detail in an analysis of Finally why citizen data scientists are on the rise, suggests that dark matter simulation packages could soon be in the hands of researchers who are experts in astronomy or materials science but not necessarily in numerical relativity or quantum field theory.

At the same time, analysts of artificial intelligence warn that as these technologies become more accessible, the barriers to entry for malicious actors are lowered, raising concerns about how powerful modeling tools might be misused. In the context of dark matter, that risk might seem abstract, but the same high performance computing and AI frameworks that power cosmological simulations can also be repurposed for less benign applications, a dual use problem highlighted in discussions of how as these technologies become more accessible, the barriers to entry for malicious actors are lowered. I see a parallel here with the open source physics codes, which can accelerate discovery but also demand a new level of responsibility from the community that builds and shares them.

Where the next breakthroughs are likely to come from

Looking across these efforts, I expect the most revealing insights into dark matter’s behavior to emerge where multiple lines of evidence intersect, and where code is explicitly designed to bridge them. That means simulations that can ingest gravitational waveforms, gamma ray spectra, galaxy surveys and quantum sensor data, then test specific hypotheses about ultralight fields, WIMPs or mirror sectors against all of them at once. The infrastructure for such cross cutting work is already visible in the way gravitational wave studies, gamma ray catalogs and quantum sensor projects like QROCODILE are framed as complementary probes, and in the way cosmological models from Northeastern and others treat the visible and dark components as a single, evolving system.

It also means that the most impactful physics code will be the least glamorous: the solvers that quietly integrate Maxwell Bloch equations, the pipelines that clean interferometer data, the frameworks that let citizen scientists run sophisticated models without breaking the underlying physics. Quantum news roundups that highlight Dec developments like Gravitational Waves May Reveal Hidden Dark Matter Around Black Holes, and dark matter origin theories that invoke mirror worlds in Jul discussions, are signals that the field is ready to move beyond simple toy models. If the community can pair that ambition with careful software engineering and a clear eyed view of AI’s risks and rewards, the next generation of code really could expose how dark matter behaves, not just that it is there.

More from MorningOverview