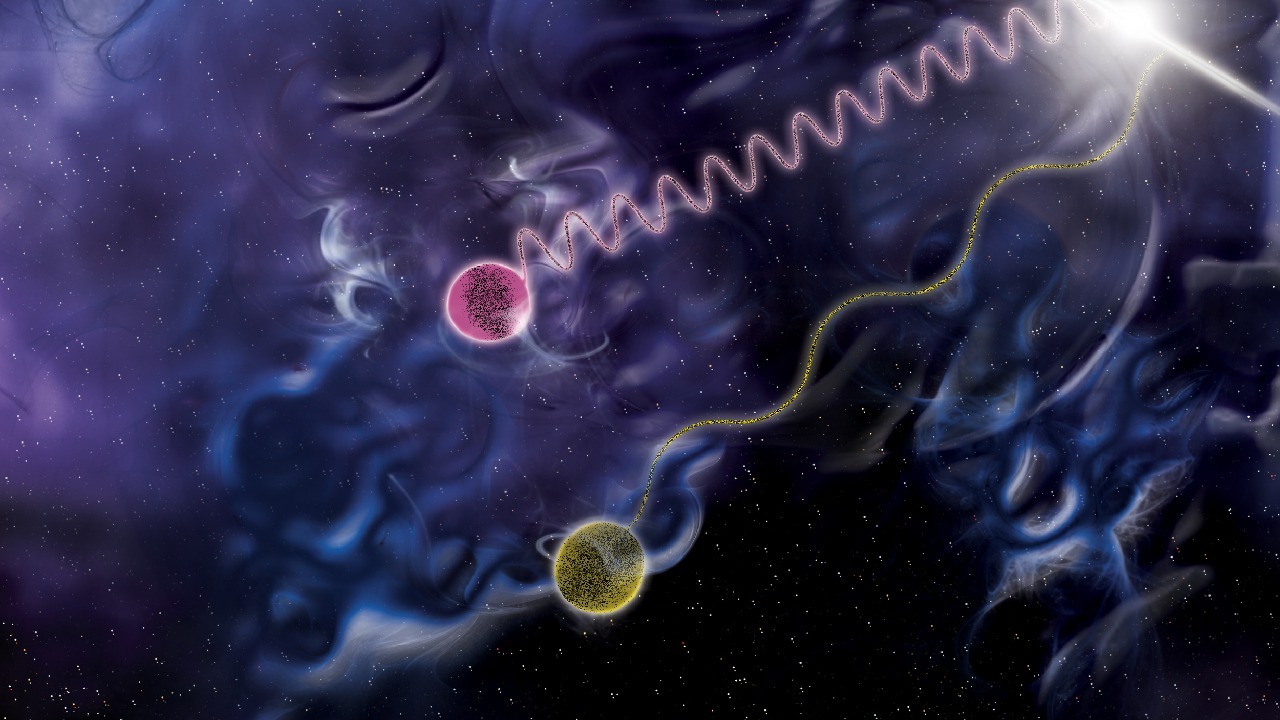

A team of physicists has created a cloud of ultracold atoms that stubbornly resists the most basic rule of everyday experience: when you pump energy into something, it heats up. Instead, this quantum gas absorbs kicks from lasers and collisions, then settles into a strange steady state where its temperature barely budges. The result is not just a laboratory curiosity, it is a direct challenge to how I usually think about thermalization, chaos and even the arrow of time in quantum matter.

A gas that will not warm, no matter how hard you kick it

The core discovery is deceptively simple to state. Researchers prepared a tightly controlled quantum gas, then repeatedly drove it with external forces that should have dumped energy into the system. In a normal fluid, that energy would spread through the particles, randomize their motion and raise the temperature. Here, after an initial response, the atoms effectively stopped taking in more energy, as if the system had found a way to shield itself from further heating despite the continued drive.

According to the description of a quantum gas that refuses to heat, the atoms were not only continually kicked but also strongly interacting, which should have made them even more efficient at sharing and absorbing energy. Instead, the experimenters watched the absorption saturate and then stall, a behavior that standard thermal physics would not predict. The work, presented as a quantum system that defies heating, has now been detailed in a study that the same team notes has been published in Science, underscoring how seriously the community is taking this anomaly.

Inside the Innsbruck experiment with ultracold cesium

To understand why this result matters, it helps to look closely at how the experiment was built. The team used ultracold atoms as a kind of quantum Lego set, assembling a one dimensional fluid where every interaction and external kick could be tuned with exquisite precision. By cooling the gas to a regime where quantum effects dominate, they turned what might have been a messy thermal system into a clean platform for testing the foundations of statistical physics.

The setup described in the Physicists Discover report centers on an experiment with ultracold atoms that reveals a quantum system that refuses to heat up even under sustained driving. In a companion account from the same group, the researchers emphasize that this quantum system that defies heating has now been published in Science, highlighting that what might sound like a paradox is grounded in a carefully peer reviewed measurement rather than a speculative theory.

Localized in momentum space: a new kind of trap

The key to the gas’s stubborn behavior lies in where, not just how, it is confined. Instead of being localized in ordinary position space, the atoms are effectively trapped in momentum space, meaning their allowed velocities are restricted in a structured way by the driving and interactions. This unusual form of localization prevents energy from spreading freely through all possible motions, so the system cannot explore the full range of chaotic states that would correspond to a higher temperature.

In technical summaries of the work, the team describes the gas as Localized in momentum space, created as a one dimensional quantum fluid of strongly interacting atoms that is periodically driven yet fails to thermalize. A separate account of A Quantum Gas That Refuses to Heat repeats that the researchers created a one dimensional quantum fluid of strongly interacting atoms confined in this momentum space landscape, reinforcing that the non heating behavior is not a numerical fluke but a direct consequence of how the allowed momenta are structured.

Extremely cold atoms and the challenge to entropy

What makes the result even more striking is the scale and precision of the system. The experimenters did not work with a handful of particles, where rare quantum effects might be easier to dismiss as finite size quirks. Instead, they controlled a large ensemble of atoms cooled to temperatures within a hair of absolute zero, then watched as the usual march toward disorder seemed to stall.

One detailed account notes that the researchers used about 100,000 atoms of caesium that they cooled within billions of a degree of absolute zero by harnessing laser and magnetic techniques. At such low temperatures, entropy and thermalization are usually described with even more care, yet the report on extremely cold atoms that defy entropy and refuse to heat up suggests the team may have captured truly new physics in how this many body quantum system processes energy.

Ultracold cesium atoms versus the rules of thermalization

From a broader physics perspective, the Innsbruck gas is a direct challenge to the textbook picture of thermalization. In that picture, a system that is periodically driven and strongly interacting should eventually behave like a hot, chaotic fluid, with energy smeared out across all available degrees of freedom. The ultracold cesium atoms in this experiment do something else entirely, absorbing energy only up to a point and then effectively refusing further heating.

One analysis frames the result as Ultracold cesium atoms that challenge the rules of thermalization and refuse to heat up, likening the repeated driving to shaking a snow globe again and again while the swirling flakes somehow never settle into a more disordered state. That same report notes that theorists have struggled with a paradox in how periodically driven quantum systems, sometimes called Floquet systems, should behave, and this experiment gives them a concrete, controllable platform where the usual assumptions about heat and chaos clearly fail.

Why “despite being continually kicked” matters

It is tempting to think that the gas’s refusal to warm is just a matter of gentle handling, that perhaps the kicks are too small or the interactions too weak to really test the system. The reporting makes clear that the opposite is true. The atoms are driven hard and collide strongly, conditions that in most experiments are chosen precisely to accelerate the march toward equilibrium and to wash out delicate quantum correlations.

In the Aug Newsroom account, the behavior is summarized with the line that, Despite being continually kicked and strongly interacting, the atoms no longer absorb energy once the localized momentum space state is established. That choice of wording is important, because it rules out the simplest escape hatches and forces me to confront the idea that the non heating is an intrinsic property of this driven quantum fluid, not an artifact of weak driving or poor coupling.

Second sound and the broader landscape of strange quantum transport

This is not the only recent result to unsettle classical intuitions about how heat and motion move through quantum matter. Over the past few years, researchers have been revisiting long predicted but elusive phenomena where temperature and entropy behave less like a diffusing smear and more like a wave. One of the most striking examples is the observation of so called second sound, where heat itself propagates in a wavelike fashion rather than simply spreading out.

A report on a separate experiment notes that, After decades of mystery, researchers have finally captured a strange effect in quantum physics known as second sound, with the work led by Martin Zwierlein and his team. While the physical systems are different, I see a common thread between a gas that refuses to heat and a fluid where heat moves like a wave: in both cases, the familiar, diffusive picture of thermal transport breaks down, replaced by more structured, quantum mechanical patterns of motion.

What this means for future quantum technologies

Beyond the conceptual shock, the Innsbruck result hints at practical possibilities. A quantum system that naturally limits how much energy it absorbs under periodic driving could be a powerful ingredient in future quantum devices, where uncontrolled heating is one of the main enemies of coherence. If engineers can learn to design materials or circuits that mimic this momentum space localization, they might build qubits or quantum simulators that remain stable even under strong control fields.

The detailed description of a quantum system that defies heating emphasizes that the effect arises in a one dimensional quantum fluid of strongly interacting atoms, a geometry and interaction regime that can, in principle, be engineered in other platforms such as superconducting circuits or photonic lattices. As I read these reports together, I see a roadmap emerging where insights from ultracold caesium, second sound in quantum gases and other non classical transport phenomena feed directly into the design of quantum hardware that treats heat not as an unavoidable nuisance but as a quantity that can be sculpted and, in some regimes, almost turned off.

More from MorningOverview