Most of what people casually call “the universe” is not where instinct suggests. Stars, planets and glowing gas clouds are only the bright frosting on a much larger cosmic cake, and the bulk of the ordinary atoms that make up that cake are effectively invisible. Astronomers have spent decades trying to track down this missing normal matter, and only recently have they been able to map where it actually resides between galaxies.

I want to walk through how scientists figured out that most of the universe’s everyday atoms are absent from stars and planets, where they finally found them, and why that discovery reshapes how we think about galaxies, black holes and even the future of cosmology itself.

What “normal matter” really means

When physicists talk about “normal” or “ordinary” matter, they mean the protons, neutrons and electrons that build everything from smartphones to spiral galaxies. This is the stuff described by the familiar periodic table, and it behaves according to the rules of atomic physics rather than the stranger laws that govern dark matter or dark energy. In technical language it is called baryonic matter, and it is the only component of the cosmos that directly forms atoms, molecules and, eventually, living beings.

Despite how tangible it feels in daily life, this baryonic component is only a small slice of the full cosmic budget. Modern measurements of the universe’s contents, summarized in Figure and Table that track everything from Luminous stars to dark energy, show that ordinary matter is vastly outweighed by invisible ingredients. Even within that modest share, only a fraction sits in stars and galaxies, which is why astronomers began to suspect that most of the atoms they expected from early universe calculations were hiding somewhere else.

How we realized most atoms are missing from stars and planets

The first hints of a problem came from a simple accounting exercise. Cosmologists could estimate how many baryons should exist by looking at the afterglow of the Big Bang and the abundance of light elements like hydrogen and helium. When they compared that theoretical tally to the amount of matter they could see in stars, planets and bright gas, the numbers did not match. The luminous content of galaxies fell well short of the predicted total, leaving a large fraction of ordinary matter apparently unaccounted for.

As telescopes improved, astronomers mapped more galaxies and hot gas, yet the shortfall persisted. Careful surveys showed that most normal matter in the universe is not found in planets, stars or even entire galaxies, a point that has been explained in detail by researchers who study how baryons are distributed on the largest scales. One overview from Dec, supported by observations from ESO and other facilities, describes how the census of ordinary matter forced scientists to look beyond the obvious bright structures and search the darker spaces between them, where the missing atoms were suspected to lurk in diffuse form, as outlined in Dec ESO.

From bright galaxies to the dim cosmic web

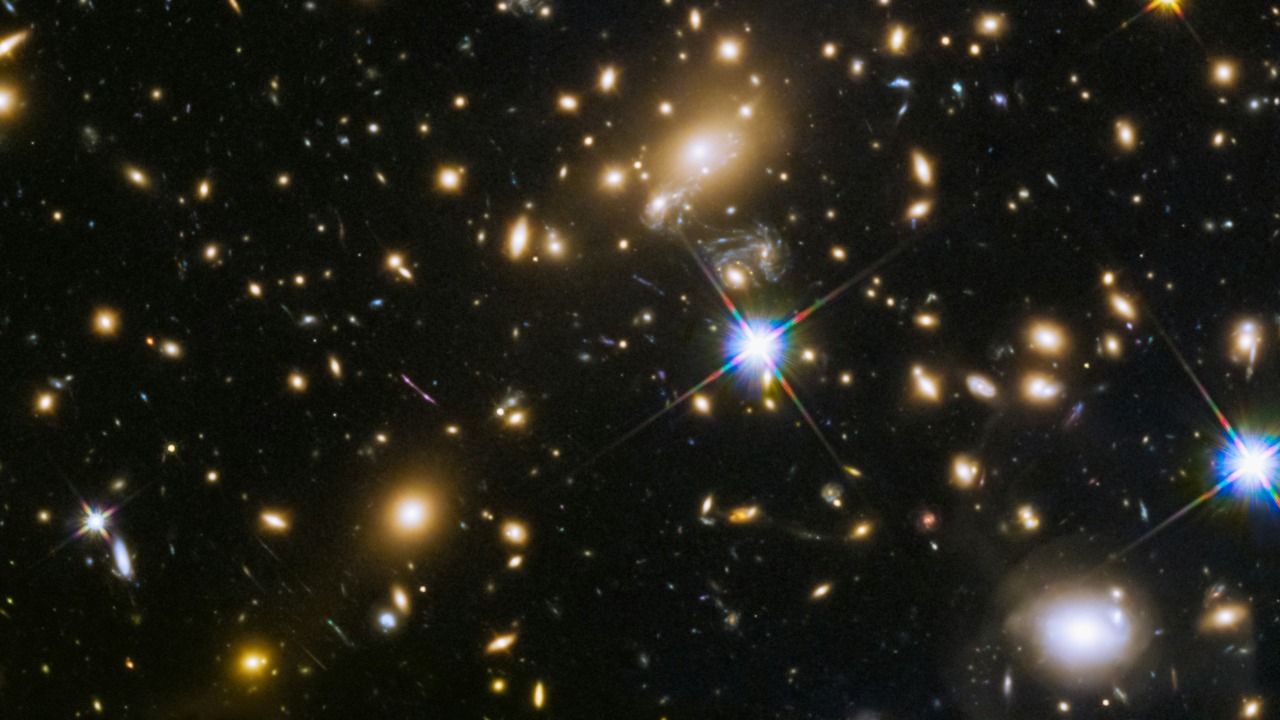

Once it became clear that galaxies alone could not host all the expected baryons, attention shifted to the vast network of filaments that connect them. Simulations of cosmic structure formation predict that gravity pulls matter into a web-like pattern, with dense knots where clusters of galaxies form and long strands of lower density gas stretching between them. If most ordinary matter was not in stars or planets, it made sense to look for it in this intergalactic scaffolding, even if that material was too thin and hot to glow brightly.

Recent work has emphasized that if you scan the sky with a telescope, you see countless galaxies, but they are only the most visible part of a much larger structure. Analyses described by Dec and others argue that the majority of normal matter is spread out in the space between galaxies rather than concentrated in the bright disks we photograph. One detailed explanation notes that most normal matter in the universe is not found in planets, stars or galaxies, and instead is distributed through this cosmic web, a conclusion that builds on the census of ordinary matter and is laid out in Most normal.

The breakthrough: tracking missing matter with fast radio bursts

Knowing that the missing atoms probably sat between galaxies was one thing, proving it observationally was another. The gas in intergalactic space is so thin that it barely emits light, which makes it extremely hard to detect directly. Astronomers needed a new kind of probe, and they found it in fast radio bursts, the millisecond flashes of radio waves that erupt from distant galaxies and race across the cosmos before reaching Earth.

Earlier this year, a team from Caltech and the Harvard Center for Astrophysics used these fast radio bursts as backlights, measuring how much the signals were slowed and dispersed by electrons in the space they crossed. By comparing the observed dispersion to the distance of each burst, they could infer how many free electrons, and therefore how much ordinary matter, lay along the line of sight. In the new study, described by Dec as a critical test of cosmological theory, the researchers showed that the amount of matter inferred from these bursts matches the expected total, meaning the missing baryons have effectively been found in the intergalactic medium, as detailed in work from Caltech and the Harvard Center for Astrophysics.

What the new census says about where matter really lives

The fast radio burst technique did more than simply confirm that the missing atoms exist, it quantified where they reside. By combining the dispersion measurements with models of how gas is distributed, the team concluded that a large majority of ordinary matter is not locked up in stars or cold galactic gas. Instead, it is spread through the warm and hot intergalactic medium that fills the space between galaxies, often at temperatures and densities that make it effectively invisible to traditional telescopes.

One key result from Jun is that “The results revealed that 76 percent of the universe’s normal matter lies in the space between galaxies, also known as the intergalactic medium, rather than in stars, planets, or in cold galactic gas.” That figure, reported in a detailed summary of the missing matter work, shows just how extreme the imbalance is between the bright structures we see and the diffuse reservoirs that actually hold most of the atoms, as laid out in 76 percent.

Violent cosmic engines that push matter into intergalactic space

Finding most of the universe’s ordinary matter between galaxies naturally raises the question of how it got there. Galaxies form in deep gravitational wells, so one might expect baryons to fall inward and stay bound. The new observations instead suggest that powerful processes inside galaxies have been ejecting gas into intergalactic space over billions of years, effectively populating the cosmic web with material that might otherwise have formed more stars and planets.

Revelations from Jun, based on the same fast radio burst data, indicate that violent cosmic forces have played a central role in this redistribution. The analysis points to energetic events such as supernova explosions and outflows from supermassive black holes as likely culprits that can heat gas and accelerate it to escape velocities, pushing it out of galaxies and into the surrounding medium. By studying radio waves hurtling through space, astronomers have been able to trace how these processes shape the large scale environment and even estimate how many fast radio bursts per year might be needed to refine the picture further, as described in Revelations made possible.

The scale of the discovery in a cosmic context

To appreciate the scale of what has been found, it helps to compare the new census to earlier expectations. For years, cosmologists knew from Big Bang calculations that a certain amount of baryonic matter had to exist, but direct observations could only account for a fraction of it. The recent work effectively closes that gap by showing that the missing share is not in some exotic form, but in ordinary gas that is simply too diffuse and hot to see easily. This resolves a long standing discrepancy between theory and observation and strengthens confidence in the broader cosmological model.

One summary from Jun describes the result as a breakthrough that identifies the location of the Universe’s “missing” matter and even records some of the most distant examples of the relevant signals. By tying the fast radio burst measurements to the large scale structure of the Universe, the study demonstrates that the predicted baryons are indeed present and distributed in a way that matches simulations of cosmic evolution, as highlighted in the report on how astronomers have discovered the Universe’s missing matter in Universe missing.

Why most ordinary matter is not in stars or galaxies

Even with the new measurements in hand, it is worth asking why stars and galaxies ended up with such a small share of the available atoms. The answer lies in the complex interplay between gravity, gas cooling and feedback from energetic events. While gravity pulls matter into potential wells and encourages collapse, processes like stellar winds, supernovae and black hole jets can heat gas and drive it back out, preventing it from forming new stars. Over cosmic time, this tug of war appears to have favored ejection and heating on large scales, leaving much of the baryonic content in a warm, diffuse state.

Analyses that focus on the distribution of ordinary matter emphasize that most of it is not in stars or galaxies because those feedback processes are remarkably efficient. One report from Dec, citing work that involved Kyiv and UNN, notes that Research has shown that 90% of the ordinary matter in the Universe is located outside of stars and galaxies, and that this material can be so hot and thin that it emits less energy in a year than the Sun emits in three days. That stark comparison, which also mentions that the story attracted 70 views in its early coverage, underscores how counterintuitive the result is for anyone used to thinking of the Universe as a collection of bright objects, as described in the account from Kyiv UNN Research Universe 90%.

What this means for the future of cosmology

Locating the missing baryons is more than a bookkeeping victory, it opens a new window on how galaxies grow and how the cosmic web evolves. With a clearer map of where ordinary matter sits, theorists can refine their models of star formation, feedback and chemical enrichment, while observers can design targeted campaigns to study the warm hot intergalactic medium in more detail. Fast radio bursts, once mysterious curiosities, are now precision tools that can trace the density and temperature of gas across vast distances, turning the entire sky into a laboratory for intergalactic physics.

For me, the most striking implication is philosophical as much as scientific. Most of the atoms that make up the universe’s normal matter are not part of any star, planet or living organism, but instead drift in enormous, nearly empty volumes of space. That realization reframes our place in the cosmos: the familiar structures we see are local condensations in a much larger, largely invisible reservoir. As future surveys build on the work from Dec, Jun and other efforts, and as instruments like ESO’s facilities push deeper into the cosmic web, our picture of where matter resides will only sharpen, but the core lesson is already clear. Most normal matter is not where our eyes are drawn, it is in the dark spaces in between, quietly shaping the universe from the shadows.

More from MorningOverview