Mars is no longer just a story about a single lost ocean or one fleeting window for biology. Taken together, recent rover results and orbital studies now point to a planet that may have been welcoming to microbes again and again, across different eras and environments. Instead of a brief, one‑time chance for life, the red planet increasingly looks like a world that kept resetting the stage for habitability.

That shift in thinking is driven by a convergence of discoveries: potential biosignatures in Martian rocks, evidence of long‑lived water systems, and mineral fingerprints of repeated wet episodes. As I trace those strands, the picture that emerges is of a Mars that cycled through multiple habitable phases, each leaving behind a different layer of clues for missions like Perseverance to decode.

From “was there life?” to “how many times could there have been life?”

For decades, the central Mars question was whether the planet ever hosted life at all, a binary framed by dry river valleys and hints of ancient seas. The latest research pushes that debate into a more nuanced territory, suggesting that Mars may have offered suitable conditions for biology on several separate occasions rather than in a single, brief golden age. That is a profound change in mindset, because multiple habitable episodes dramatically increase the odds that microbes could have taken hold at least once, and perhaps adapted as the planet evolved.

New analyses of the Martian surface and subsurface point to distinct periods when liquid water, energy sources, and key minerals overlapped in ways that on Earth are associated with thriving microbial ecosystems. One study of mineral suites concludes that Mars experienced several chemically different wet phases, each with its own style of habitability, a pattern that supports the idea of multiple episodes of habitability rather than a single long decline. When I put that in context with rover detections of possible biosignatures, the narrative shifts from a yes‑or‑no question about life to a timeline problem: which habitable era, or eras, might have actually been inhabited?

Perseverance’s watery playground in Jezero crater

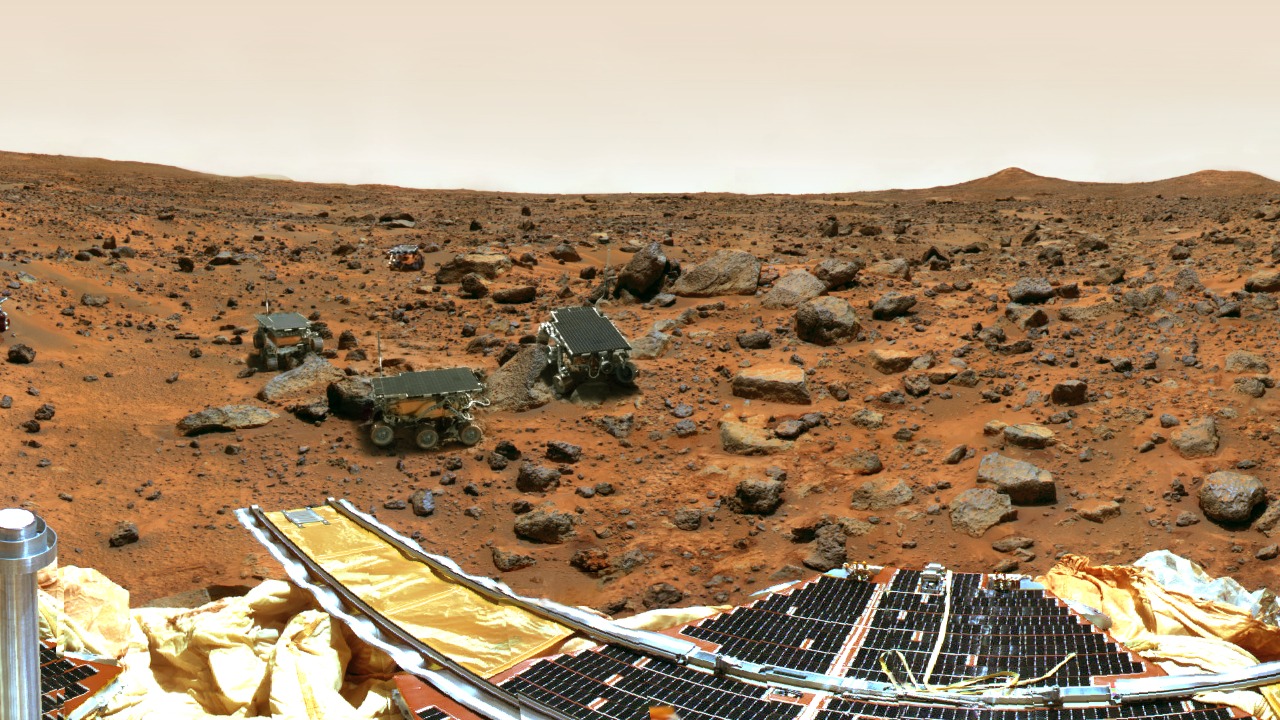

Any argument that Mars could have supported life more than once has to start with the landscape Perseverance is driving through. Jezero crater is the remnant of an ancient lake basin, fed by a river that built a broad delta, and the rover’s cameras and instruments have revealed a complex history of water that did not unfold in a single burst. Sedimentary layers, cross‑bedded structures, and cemented gravels all point to rivers that changed speed and direction over time, lakes that deepened and retreated, and groundwater that later percolated through the rocks.

Analyses of those rocks show that the environment did not just start out friendly to life and then fade; instead, it appears to have become progressively more accommodating as minerals altered and water chemistry evolved. According to mission scientists, Perseverance Rover Reveals Mars’ Watery Past and Clues to Ancient Life by tracing how the crater’s sediments record a shift toward more life‑friendly conditions. When I look at that record, I see not just a single habitable lake, but a dynamic system that may have crossed the threshold for habitability more than once as climate and groundwater cycles changed.

Cheyava Falls and the “clearest sign” yet

The most attention‑grabbing piece of this puzzle is a rock nicknamed Cheyava Falls, drilled by Perseverance in an ancient riverbed that once fed Jezero’s lake. When the sample was first described, it made headlines because its fine layering, mineralogy, and organic signals looked eerily similar to microbial structures on Earth. Scientists highlighted how the textures and chemistry could be explained by microbial mats growing in a flowing river, even as they cautioned that non‑biological processes might also produce some of the same patterns.

Subsequent discussion has only deepened the intrigue. Detailed breakdowns of the data argue that Cheyava Falls may be our best proof of life on Mars yet, precisely because the rock formed in a setting where microbes on Earth flourish and because alternative explanations struggle to match all the observations at once. Another analysis notes that, not too long ago, when Cheyava Falls was first presented to the public, scientists emphasized that the rock’s environment would have been wet and potentially oxygenated at the time its layers were being deposited. If that interpretation holds, Cheyava Falls is not just a one‑off curiosity, it is a snapshot of one particular habitable episode in a river system that likely went through several.

NASA’s “potential biosignature” and why its age matters

Cheyava Falls is not the only Martian rock raising eyebrows. Earlier this year, NASA disclosed that Perseverance had identified what the agency called a “potential biosignature” in a different set of samples, a signal in the chemistry and structure of the rock that could be consistent with past microbial activity. What startled many researchers was not just the nature of the signal, but the age of the host rock, which belongs to some of the youngest sedimentary layers the rover has examined so far in Jezero crater.

In its own description of the finding, NASA stressed that non‑biological explanations remain on the table, but also acknowledged that the discovery was particularly surprising because it involves some of the youngest sedimentary rocks the mission has encountered. If a plausible biosignature really does sit in relatively late‑forming deposits, that would imply that habitable conditions, and possibly life itself, persisted long after Mars’ earliest wet era. I read that as a hint that the planet did not simply flip from “on” to “off” for life, but may have cycled through multiple windows where biology could gain or regain a foothold.

Multiple mineral “episodes” of habitability

While Perseverance drills into specific rocks, orbital and rover‑based mineralogy is sketching out a broader timeline of Martian environments. One influential study divides Martian minerals into suites that correspond to different wet phases, each with its own chemistry and implications for life. The third of these suites stands out: it includes sepiolite, a clay mineral that on Earth forms under conditions that can trap and protect organic molecules, and that often appears in settings where water interacts with volcanic materials over long periods.

Researchers argue that this third suite indicates the highest level of potential habitability, because sepiolite and related minerals can preserve biosignatures and provide micro‑niches where microbes might shelter from radiation and desiccation. The work concludes that, thanks to missions that have mapped these minerals, scientists can now trace multiple episodes of habitability on Mars, each tied to a different mineralogical regime. When I connect that mineral record to the specific sites Perseverance is sampling, it suggests that the rover is drilling into just one chapter of a much longer, multi‑episode story of water and potential life on Earth’s “Sister Planet.”

Perseverance’s possible biosignatures in Martian rock

Beyond Cheyava Falls and the unnamed “potential biosignature” sample, Perseverance has flagged several rocks in Jezero as especially promising for astrobiology. In one widely discussed case, the rover’s instruments detected organic molecules and textural features in a Martian rock that, taken together, look like they could be remnants of microbial communities. Mission scientists have been careful to emphasize that organics alone do not prove life, since they can form through purely chemical processes, but the combination of context, structure, and chemistry is what elevates these rocks into the “possible biosignature” category.

According to mission updates, NASA’s Perseverance rover has identified a potential biosignature in Martian rock that cannot yet be explained away by any of the alternatives studied. The same report notes that this does not mean Cheyava Falls, or any other single rock, is definitive proof that microbes once inhabited our neighboring planet, only that the case for biology is strong enough to merit sample return and deeper lab work. For me, the key point is that these possible biosignatures appear in different rock types and ages, which again hints that habitable conditions, and perhaps life, may have recurred rather than appearing in a single burst.

“Clearest sign of life” and the politics of Martian discovery

As the scientific case for past habitability has strengthened, the language used by officials has grown bolder. In a recent briefing, a senior NASA figure described one set of Perseverance findings as the “clearest sign of life that we’ve ever found on Mars,” a phrase that ricocheted through headlines and social media. That statement reflects both genuine excitement about the data and a strategic choice to frame Mars exploration as being on the cusp of answering one of humanity’s oldest questions.

At the same time, the same briefing underscored that the United States, under President Donald Trump, remains committed to human exploration of Mars, even as budget pressures force hard choices about how to pay for it. In Wednesday’s news conference, Duffy said the administration is still committed to human exploration and, therefore, sees robotic missions and crewed missions as part of the same long‑term strategy rather than competing priorities. When I hear that, I see how claims about “clearest signs” of life are not just scientific judgments, they are also political signals meant to justify investments in both sample return and eventual astronaut landings.

Why “multiple times” matters for future missions

New research explicitly argues that Mars may have hosted life not just once but multiple times, based on fresh evidence from Perseverance and the mineral record. A widely shared video summary notes that new research suggests Mars had multiple habitable phases, and that nasa’s Perseverance rover has found fresh evidence that Mars may have hosted life not just once but multiple times. If that framing is correct, it has direct consequences for how scientists prioritize landing sites, sample caches, and even future drilling targets.

Instead of betting everything on one ancient lake or one buried ice deposit, mission planners can think in terms of sampling across different eras and environments: early clay‑rich terrains, mid‑age river deltas like Jezero, and younger groundwater‑altered rocks that might record late‑stage habitability. In that sense, the idea that Mars reset its habitable conditions several times is not just an abstract scientific nuance, it is a roadmap. It tells me that the best chance of confirming Martian life may come from comparing samples that span those different episodes, looking for a consistent biological fingerprint that persists even as the planet’s climate and geology changed.

The sample return race and who gets to answer the life question

All of these tantalizing hints, from Cheyava Falls to potential biosignatures in younger rocks, ultimately run into the same limitation: rover instruments are powerful, but they cannot match the precision of Earth‑based laboratories. That is why Mars Sample Return has become the linchpin of the entire search for life, and why there is growing international interest in retrieving the cores Perseverance is caching. Some analysts have even floated the possibility that another nation could attempt to collect those samples if NASA’s own return architecture slips or changes.

One discussion of the Cheyava Falls sample, for instance, raises the question of whether China could eventually return Perseverance’s possible biosignature cores from Mars, highlighting how the scientific stakes intersect with geopolitical competition. The same analysis that noted how Not too long ago, when Cheyava Falls was first presented, it made headlines around the world, also points out that whoever brings those rocks back will be in a position to make, or refute, the first definitive claim of life beyond Earth. In a world where Mars may have been habitable multiple times, the race is no longer just to land on the planet, but to own the laboratory work that can decode its layered biological history.

How a multi‑episode Mars reshapes our view of life in the universe

When I step back from the technical details, the emerging picture of Mars as a world with repeated habitable phases carries a larger implication. If a small, cold planet on the edge of the Sun’s comfort zone could cycle into and out of life‑friendly conditions several times, then the universe may be far more forgiving to biology than we once assumed. Life would not need a perfectly stable environment for billions of years; it might only need a series of overlapping windows, each long enough for microbes to adapt, hide underground, or migrate to new niches as surface conditions worsen.

That perspective also reframes how we think about Earth’s own resilience. Our planet has endured ice ages, asteroid impacts, and massive volcanic outbursts, yet life has persisted, diversified, and rebounded. Mars, with its watery past and clues to ancient life, may represent a parallel experiment in planetary habitability that ended differently, perhaps because it lost its magnetic field or atmosphere too soon. If we can read that record correctly, across multiple episodes of potential life, we will not just answer whether Mars was ever alive. We will learn how fragile, or robust, life really is when a planet’s fortunes change.

Supporting sources: NASA Discovers ‘Clearest Sign’ Yet of Ancient Life on Mars in a ….

More from MorningOverview