Warnings that artificial intelligence will wipe out jobs and outthink its creators have become a familiar soundtrack to the tech boom. Yet some of the field’s most influential builders are now pushing back, arguing that today’s systems are powerful but narrow tools, not imminent replacements for human judgment or creativity. Their message is not that AI is harmless, but that its real impact will depend on how people choose to use it.

Instead of a sudden takeover, these researchers and executives describe a slower, more negotiated future in which algorithms handle specific tasks while humans still set goals, define values, and remain in charge. I see their arguments converging on a simple idea: the technology is advancing quickly, but its limits are just as important as its breakthroughs when we think about work, power, and responsibility.

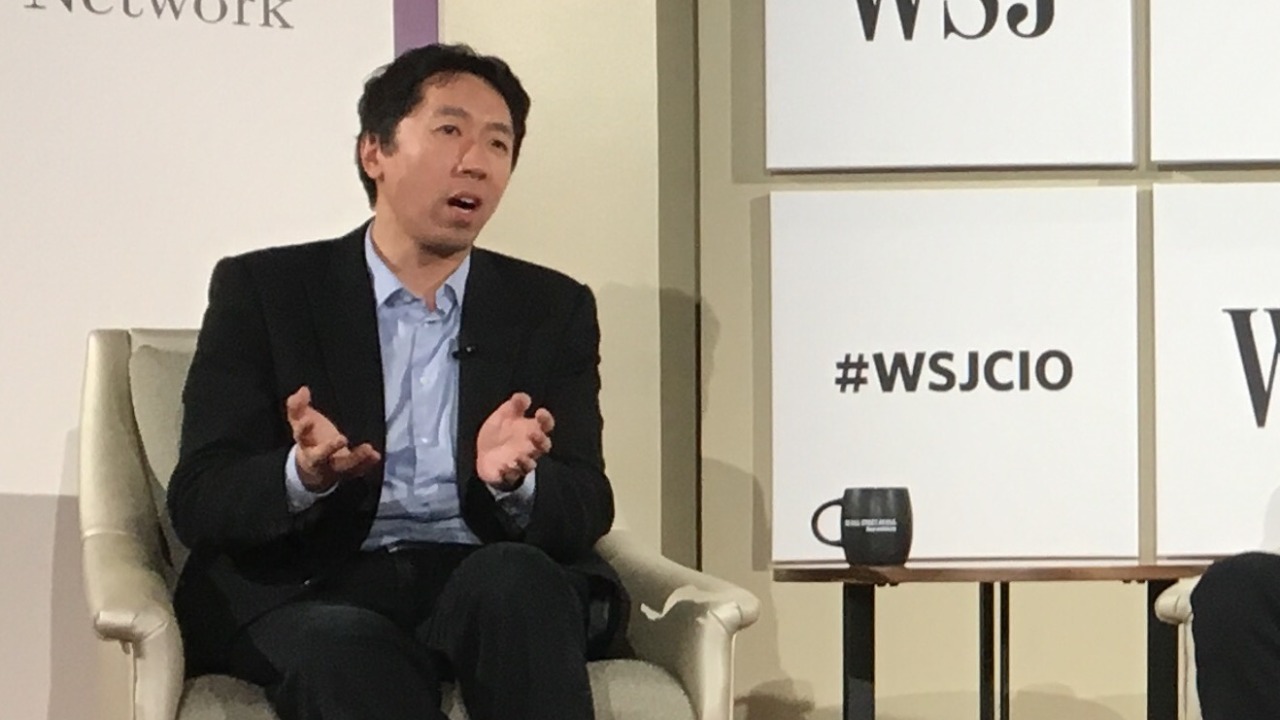

Why Andrew Ng calls today’s AI “limited”

Andrew Ng has spent years at the center of modern machine learning, so his insistence that current systems are “limited” carries unusual weight. He argues that the models behind chatbots and image generators excel at pattern recognition inside carefully defined boundaries, but they still lack the broad understanding and common sense that people routinely bring to unfamiliar situations. In his view, treating these tools as if they were general minds risks both overhyping their capabilities and underestimating the human skills that remain essential.

Ng’s skepticism is not a dismissal of progress, it is a reaction to what he sees as exaggerated claims that jobs or entire professions are on the verge of being fully automated. He has described AI as a revolution in how software is built and deployed, but he also stresses that the technology will not replace humans anytime soon, a point he has repeated in separate interviews that both describe him as limited in what it can do and as An AI pioneer. That tension, between transformative potential and concrete constraints, is the starting point for a more realistic conversation about where the technology is actually headed.

From “worst career advice” to new kinds of coding work

One of Ng’s sharpest critiques is aimed at the idea that young people should avoid learning to code because AI will do it for them. He has warned that we may “look back on that as some of the worst career advice ever given,” arguing that as tools improve, they tend to expand the number of people who can participate in a field rather than eliminate it. In software, that means more people will be able to build applications, automate tasks, and customize systems, even if they rely on AI to generate boilerplate functions or translate between programming languages.

Ng’s point is that when coding becomes easier, as it already has with high level languages and frameworks, the demand for people who understand how to structure problems and evaluate solutions usually grows. Instead of replacing developers, he expects AI assistants to shift their focus toward architecture, security, and product thinking, while the machine handles repetitive syntax. That is why he pushes back so strongly on blanket claims that programming is a dead end, a stance echoed in coverage that quotes him criticizing that advice and describing how, as coding becomes easier, it opens doors rather than closes them, a theme that appears in the reporting that begins with “Dec” and “Because” in the same interview.

Yann LeCun: humans stay the boss

Meta AI chief scientist Yann LeCun takes a similarly grounded view, even as he works on some of the most ambitious research in the field. He has argued that the kind of artificial superintelligence often imagined in science fiction, systems more advanced than human thinking in every respect, is not what exists today and may not be the form that future AI takes. Instead, he expects a proliferation of specialized models that can reason about particular domains while still operating under human direction.

LeCun has been explicit that people will remain in charge of these systems, saying that even as AI grows more capable, humans are going to be their boss. In a talk that highlighted how Artificial superintelligence is commonly understood, he pushed back on the idea that such entities are around the corner or destined to dominate their creators. His argument reframes the debate: the real question is not whether AI will seize control, but how institutions design incentives, guardrails, and interfaces so that people can supervise and override automated decisions.

Beyond chatbots: the next wave of AI research

LeCun has also been one of the most vocal critics of treating today’s generative models as the endpoint of AI progress. He has described systems that simply predict the next word or pixel as impressive but fundamentally limited, because they lack persistent memory, grounded understanding of the physical world, and the ability to plan over long horizons. In his view, the next wave of research will need new architectures that can learn from interaction, not just static datasets, if they are to approach the flexible intelligence people display.

That perspective came through in a detailed discussion of AI challenges, where he emphasized the urgent need for open source development to prevent regulatory capture and to ensure that innovation is not locked inside a handful of companies. He also outlined how current generative models fit into a broader roadmap and argued that the next wave of AI will require different techniques, a point he made in a conversation that highlighted How these systems might evolve. For workers and policymakers, that is a reminder that the tools in use today are not static, but they are also not the all purpose intelligences that some hype suggests.

“Amplify” rather than “take over”

LeCun’s public comments often return to a simple phrase: AI will not take over humans, it will amplify human intelligence. That framing matters because it shifts the focus from replacement to collaboration, from a zero sum contest between people and machines to a question of how to combine their strengths. In practice, that could mean doctors using diagnostic models to catch rare conditions, lawyers relying on search tools to surface relevant cases, or designers iterating faster with generative imagery, while still making the final calls themselves.

In an interview where he spoke as Meta AI chief, Yann LeCun argued that the most realistic future is one in which algorithms extend what people can do, rather than displacing them entirely. He described AI as a set of tools that will sit alongside human decision makers, not above them, insisting that “AI will not take over humans, it will amplify human intelligence,” a line that has been widely quoted and that appears in coverage of Meta AI. I see that as a direct counter to the narrative that automation is a one way street toward obsolescence, and as a call to design workplaces where augmentation is the default.

Google’s Sundar Pichai and the future of coding jobs

Google CEO Sundar Pichai has added his own voice to the argument that AI will not instantly erase technical careers, particularly in software development. He has said plainly that AI will not replace human coders anytime soon, even as his company rolls out tools like code completion and automated bug detection inside products such as Android Studio and Google Cloud. For Pichai, these features are meant to reduce drudgery and help developers move faster, not to make them redundant.

That stance aligns with Ng’s view that easier coding expands the field rather than shrinking it. Pichai has framed AI as a way to bring more people into programming, including those who might start by describing what they want in natural language and then refine the generated code. His comments, reported under the headline that “AI will not replace human coders anytime soon,” underscore that even the executives building these tools expect humans to stay in the loop, a point captured in coverage that quotes Google CEO Sundar Pichai directly. For students weighing whether to learn Python or JavaScript, that is a concrete signal that the skills remain valuable.

How media hype distorts public fears

Despite these measured messages from insiders, public debate about AI often swings between utopian promises and apocalyptic warnings. Headlines about chatbots passing exams or generating photorealistic images can create the impression that machines already match human reasoning, while stories about mass layoffs sometimes attribute complex economic shifts solely to automation. The result is a climate in which people either overestimate what current systems can do or assume that their own skills are about to be rendered obsolete overnight.

Reporting on Ng’s comments illustrates how nuance can get lost. One article that describes him as an AI pioneer who says the technology is limited and will not replace humans anytime soon also notes his long history as a cofounder of major projects and as a leader at the Chinese tech titan Baidu, but the most viral takeaway tends to be the reassurance that jobs are safe. Another piece, written by Jared Perlo and labeled with “Sat” in its byline, similarly highlights that an AI pioneer says the technology is limited and will not replace humans anytime soon, while also sketching his broader career, including his role at Baidu, in a way that can be seen in the coverage linked under An AI and Jared Perlo. I read those stories as attempts to balance caution with optimism, but they also show how easily a complex argument can be flattened into a single reassuring line.

What “limited” really means for workers

When Ng and LeCun describe AI as limited, they are not saying it is weak or irrelevant. They are pointing out that these systems operate within the data and objectives they are given, and that they lack the broad situational awareness that people use to navigate messy, real world problems. For workers, that means the most resilient roles are likely to be those that combine domain expertise, communication, and ethical judgment with the ability to use AI as a tool, rather than those that consist solely of predictable, repetitive tasks that can be fully specified in code.

In practical terms, that could look like a customer support agent who uses a chatbot to draft responses but still decides how to handle an angry caller, or a financial analyst who relies on machine learning to flag anomalies but still interprets what they mean for a client’s strategy. The pioneers quoted in these reports are effectively advising people to lean into the parts of their jobs that are hardest to formalize, while also learning enough about AI to supervise it. Their message is not that everyone must become a machine learning engineer, but that understanding how these tools work, and where they fail, will be a core professional skill.

Why human oversight is not optional

Across these perspectives, one theme stands out: human oversight is not a temporary crutch on the way to full automation, it is a permanent requirement. LeCun’s insistence that humans will be the boss of AI, Ng’s focus on the limits of current models, and Pichai’s reassurance about coding jobs all assume that people will continue to set objectives, monitor outcomes, and correct errors. That is not just a philosophical stance, it is a practical response to the reality that AI systems can hallucinate, embed bias, or behave unpredictably when pushed outside their training data.

Keeping humans in charge also means building institutions and regulations that reflect this division of labor. LeCun’s call for open source development to avoid regulatory capture, Ng’s warnings about overhyping automation, and Pichai’s framing of AI as an assistant rather than a replacement all point toward a future in which transparency, accountability, and shared control matter as much as raw performance. I see their convergence as a kind of informal manifesto from the people closest to the technology: AI will keep getting better, but it will not absolve humans of responsibility, and it will not, on its own, decide what kind of society we build with it.

More from MorningOverview