Mars has been sold as a bold escape plan, a backup world for a species that keeps testing the limits of its first one. The harder I look at the technical and ethical record, the more that dream reads like a trap, not a lifeboat, because the planet’s basic physics and chemistry are set up to break human bodies and fragile systems. The strongest reason we should not go is simple: long before any colony could become self-sufficient, the environment would quietly and irreversibly damage the people sent there.

The real trap: a one‑way health crisis

The central problem with Mars is not rockets or money, it is that the planet is fundamentally hostile to human biology in ways we cannot yet fix. A crew would spend months in deep space, then years on a surface that batters cells with radiation, weakens bones and muscles, and loads lungs with toxic dust, all while medical evacuation is effectively impossible. That combination turns every mission into a slow medical experiment on volunteers whose bodies are being pushed far beyond any conditions human evolution has prepared for.

Space agencies already list the major health hazards of deep space as radiation, isolation, altered gravity, and closed life support systems, and they acknowledge that these stressors interact across the entire human system, from the brain to the cardiovascular network to the immune response, rather than acting in isolation, as detailed in one overview of the major health hazards. On Mars, those risks do not end when the crew lands, they intensify, because the planet lacks the protective magnetic field and thick atmosphere that make Earth survivable. The strongest argument against going is that we would be deliberately placing people into a chronic, whole‑body health crisis with no realistic way to bring them home once the damage becomes clear.

Radiation: the unsolved fatal flaw

Radiation is the single most unforgiving constraint, and it is where the trap tightens first. In interplanetary space, crews are exposed to high‑energy cosmic rays and solar particles that are largely deflected at Earth by its magnetic field and thick air, but Mars has neither, so the bombardment continues on the surface. Analyses of the journey emphasize that the lack of a global magnetic field on Mars, combined with its thin atmosphere, means high‑energy cosmic rays and solar energetic particles would hit crews throughout the trip there and back and then during their stay, which is why some researchers argue that current shielding concepts are not yet sufficient for long missions, a point underscored in a detailed look at these radiation challenges. Unlike many engineering problems, this is not something that can be patched with a software update or a quick hardware swap once a crew is en route.

Even optimistic advocates concede that the radiation problem is not remotely solved, and some specialists, such as the scientist identified as Iess in one widely discussed analysis, argue that the doses expected on a Mars mission would exceed anything human biology has ever endured, a concern captured in a discussion of the fatal flaw of Mars missions. The trap here is that radiation damage accumulates silently, increasing lifetime cancer risk, degrading the nervous system, and potentially impairing cognition, all while crews are expected to operate complex machinery and make life‑or‑death decisions. Sending people into that environment without a proven way to keep doses within known safe limits is less exploration and more a slow‑motion medical trial with no control group.

A planet without Shields: Mars versus Earth’s protection

On Earth, we rarely think about the invisible infrastructure that keeps us alive, but it is exactly what Mars lacks. Our planet’s magnetic field and dense atmosphere act as Shields that deflect and absorb much of the solar wind and cosmic radiation that stream through the solar system, turning potentially lethal space weather into auroras and minor satellite glitches. By contrast, Mars is a terrestrial planet that, as one technical study notes, does not have a strong magnetic field like the Earth, which leaves its upper atmosphere directly exposed to the solar wind and shapes a weak, induced magnetic field instead, a configuration described in detail in work on solar wind influences on Mars. That physical reality is not a minor inconvenience, it is the backdrop for every health and engineering decision on the planet.

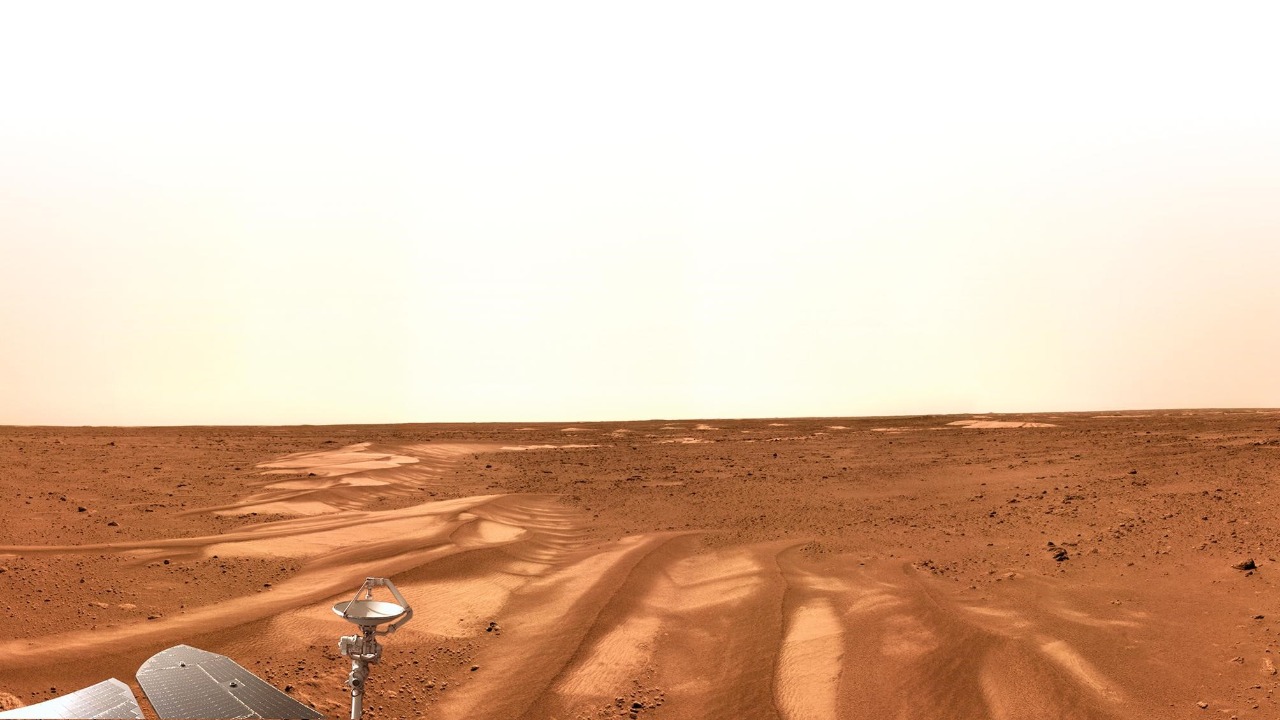

Because Mars has already lost most of its atmosphere to space, its surface pressure is less than 1 percent of Earth’s, which means there is almost no natural shielding from high‑energy particles, a point that planetary scientists emphasize when they warn that the lack of a global magnetic field and thin air make high‑energy cosmic rays and solar particles a constant hazard for crews, as summarized in a recent analysis of challenges facing human exploration. Any long‑term base would therefore have to be buried under meters of regolith or water, turning the romantic image of settlers strolling under pink skies into a more claustrophobic reality of people living in tunnels and caves to avoid a sky that is trying to kill them.

Gravity, bodies, and the point of no return

Even if radiation could be tamed, Mars still pulls on the human body in ways that make permanent settlement a one‑way bet. The planet’s gravity is about 38 percent of Earth’s, which is enough to keep dust on the ground but not enough to maintain bones, muscles, and cardiovascular systems in the way our physiology expects. We already know from orbital missions that in microgravity, bone density can drop at a rate of about 1 percent per month and muscle mass can erode quickly, leading to weakness and a higher chance of fractures, as explained in a primer on how other serious effects of weightlessness show up in astronauts. Mars gravity is higher than that, but there is no evidence that it is high enough to prevent long‑term degradation, especially over years.

Some space advocates imagine that the human body would adapt over time to low gravity worlds like the Moon or Mars, but even they acknowledge that returning to Earth after such adaptation could become extremely difficult, a concern voiced in discussions of how the human body might adapt to reduced gravity. The trap is that a generation born or raised on Mars might never be able to visit Earth without intensive medical support, effectively locking them into a weaker, more fragile version of humanity that depends on a hostile planet’s infrastructure to survive.

Dust, soil, and the toxic ground underfoot

Beyond radiation and gravity, the Martian surface itself is chemically dangerous in ways that cut against the fantasy of simple greenhouses and backyard potato patches. Analyses of Martian regolith and atmospheric chemistry indicate that perchlorates, which are reactive chlorine‑oxygen salts, are abundant in Martian soil and dust, and that these compounds can be highly toxic to humans if inhaled or ingested, a point that has been highlighted in both scientific discussions and popular explanations of how Martian soil chemistry differs from Earth’s. Any attempt to grow food in local dirt would therefore require complex processing to remove or neutralize these salts, adding another layer of engineering to every meal.

More recent work has focused on the health risks of Martian dust itself, which is fine enough to penetrate deep into lungs and contains compounds such as chromium that, if inhaled over long periods, could exceed recommended safe doses on Earth, as shown in studies that describe how Martian Dust Will Be a Health Hazard for Astronauts. Another set of findings reported that chronic health effects would result from prolonged exposure, because the particles are small enough to travel deep into the lungs and even enter the bloodstream, a warning reinforced by studies of Martian dust. In practice, that means every airlock cycle, every suit breach, and every maintenance task outside becomes a potential exposure event, slowly loading settlers’ bodies with particles their lungs were never meant to handle.

Technology that is “not up to snuff yet”

Proponents of Mars settlement often respond that technology will solve these problems, but the current state of the hardware suggests otherwise. Even optimistic explainers aimed at general audiences concede that our technology is not up to snuff yet for safe, routine human travel to Mars and that, for now, it is far more realistic to explore the cosmos with machines, a point made bluntly in one video that notes how Our technology is not up to snuff yet. Life support systems that can run for years without resupply, closed‑loop agriculture that can handle dust and perchlorates, and radiation shielding that does not make spacecraft impossibly heavy all remain in various stages of research and early testing.

Even the launch and landing phases are fraught, with one widely shared breakdown of risks pointing out that rockets can fail before leaving Earth, that landing on Mars involves threading a narrow corridor of thin air with heavy vehicles, and that the radiation problem persists throughout, as illustrated in a graphic look at the top ways a trip to Mars could kill you. When I weigh those stacked technical uncertainties against the certainty of harsh environmental conditions on the ground, the idea of sending crews now looks less like bold exploration and more like building a fragile outpost on the edge of a cliff during an ongoing storm.

Psychology, politics, and the limits of Mission control

Even if the engineering pieces fell into place, the human factors and political context remain deeply underappreciated. One scholarly assessment of whether we should and could send people to Mars concludes that a Mission to Mars is currently beyond the technological, political, and mental scope of humanity, and it warns that deep faith in the power of technology can blind planners to cascading risks, including extensive fires and other emergencies that probably will occur in closed habitats, as argued in a review of why Mission to Mars is currently beyond scope. Long‑duration isolation, conflict within small crews, and the psychological strain of knowing that help is months away are not side issues, they are central to whether any settlement can function.

On the political side, even enthusiasts within the space community are starting to voice skepticism that the necessary tools, systems, and logistics exist, with one detailed community post arguing that we are not going to Mars anytime soon, maybe never, because despite the headlines we are building launchpads to nowhere, a sentiment captured in a discussion titled Mars, Maybe never. When I factor in shifting political priorities, budget cycles, and the reality that any Mars program would span decades and multiple administrations, the risk is that crews could find themselves dependent on a supply chain and support network that their home planet no longer has the patience or resources to maintain.

Ethics, extremophiles, and planetary protection

Beyond the practical risks to human crews, there is a quieter ethical trap in treating Mars as a blank canvas. Microbiologists and philosophers have pointed out that hardy extremophiles from Earth, the very sorts of organisms that can survive in radiation‑blasted deserts and deep ice, are exactly the ones that could persist indefinitely on the Martian surface if we carry them there, a concern laid out in an argument that humans should not colonize Mars. Once such microbes are introduced, they could contaminate potential native ecosystems or future scientific investigations, making it impossible to tell whether any detected life is truly Martian or just a resilient hitchhiker from Earth.

Policy experts in planetary protection warn that Mars exploration must grapple with the fact that humans take microbes with them wherever they go and that large‑scale human activity on the planet could hinder our ability to study any indigenous biology, a tension explored in work on how Mars exploration and planetary protection intersect. If we rush to plant flags and build domes, we may not only endanger the settlers but also erase a unique scientific record of how life might arise on another world, trading irreplaceable knowledge for a precarious outpost.

The terraforming mirage and Musk’s fixer‑upper pitch

Part of the allure of Mars comes from the idea that we could eventually transform it into something more Earthlike, but the scale of that project is often glossed over. Advocates of terraforming talk about Creating a Thicker Atmosphere The goal of making the Red Planet’s air dense enough to trap heat and reduce the need for pressurized habitats, as described in a manifesto that outlines how Creating a Thicker Atmosphere The goal would be pursued. Yet the energy required to release enough gases, the timeframes involved, and the unknown side effects on climate and dust cycles make this less a plan and more a thought experiment.

Even Elon Musk, who has become the most visible champion of Mars settlement, has admitted that Mars is very inhospitable and described it as a fixer‑upper of a planet, saying that first you have to live in transparent domes before you can transform it into an Earthlike planet, a framing captured in his conversation with Musk on Colbert. When I weigh that candid description against the health and environmental hazards already outlined, the idea of betting our species’ future on a fixer‑upper that might take centuries to renovate looks less like vision and more like a dangerous distraction from stabilizing the only fully habitable world we currently have.

Cheaper, safer alternatives: robots and orbital habitats

None of this means we should turn our backs on Mars entirely, but it does suggest that sending people there now is the wrong tool for the job. Robotic missions have already shown that machines can traverse the Martian surface, drill into rocks, and analyze atmospheric chemistry without risking human lives, and some analysts argue that we should lean into that advantage, using advanced rovers and orbiters to explore the cosmos with machines rather than rushing crews into harm’s way, a perspective echoed in a video that bluntly states that we should explore the cosmos with machines. With improving autonomy and teleoperation, especially from nearby orbits, the scientific return per dollar and per unit of risk is likely to remain higher for robots than for human explorers for a long time.

At the same time, if the goal is to learn how humans cope with long‑duration space living, there are safer testbeds closer to home. Concepts for orbital habitats and stations at locations like the Earth‑Moon Lagrange points, or even large rotating structures that simulate gravity, could let us study radiation shielding, closed‑loop life support, and psychological dynamics without committing crews to a distant gravity well. Some space advocates have argued that such platforms, combined with lunar bases, would be a more rational stepping stone than a rushed Mars push, a view that aligns with critiques that we shouldn’t send humans to Mars until we have proven systems and a clearer understanding of the risks.

The strongest reason to stay away, for now

When I pull these threads together, the picture that emerges is not of a heroic frontier waiting to be tamed, but of a planet that quietly undermines every human system we rely on, from DNA repair to agriculture to politics. Radiation that we cannot yet block, gravity that may permanently weaken settlers, dust that poisons lungs and equipment, and a thin, unshielding atmosphere all combine to make Mars a place where every breath, every step outside, and every year lived carries compounding risk. That is the core of the trap: once we commit people there, the environment will begin reshaping their bodies and societies in ways that are hard to reverse and even harder to justify.

There are still powerful cultural and emotional forces pushing us toward Mars, from glossy depictions of survival stories to charismatic entrepreneurs promising multi‑planetary salvation, narratives amplified in popular videos that dramatize why we should never go to Mars and podcasts that list fatal threats facing any crew, such as the one produced by WON that outlines five fatal threats. Yet the more I weigh the evidence, the clearer it becomes that the bravest choice right now is not to plant a flag on the Red Planet, but to admit that sending humans there today would be gambling with lives in an environment that is structurally stacked against them, and to focus instead on the robotic, orbital, and Earth‑based work that can actually secure our future.

Rethinking ambition before it hardens into dogma

Space culture has a way of turning ambitious ideas into articles of faith, and Mars has become the ultimate example of that tendency. Commentators who question the rush are sometimes dismissed as lacking vision, yet careful critiques point out that a Mars colony would require settlers to spend most of their time under a few feet of dirt to avoid radiation and that key industrial inputs, such as certain metals, are rare in asteroids and not trivial to source on Mars either, as argued in an opinion that begins with the blunt observation, Thus, our intrepid explorers or settlers must stay under a few feet of dirt most of the time if they plan to stay long and remain healthy, a line that anchors a broader case against Mars. When I compare that subterranean reality with the open‑sky imagery used to sell the dream, the gap between marketing and physics becomes hard to ignore.

Even within the spaceflight community, there is a growing recognition that ambition must be matched to evidence. Some analysts argue that a more realistic path involves building up cislunar infrastructure, perfecting closed‑loop habitats in orbit, and using robotic scouts to map resources and hazards on Mars long before any crewed landing, a strategy that aligns with the view that Mission to Mars is currently beyond our scope and that deep faith in technology alone is not a plan, as laid out in the argument against sending humans and the scholarly assessment of mission limits. If we can resist the urge to treat Mars as destiny and instead see it as one option among many, we may find better, safer ways to expand human presence in space without walking willingly into a planetary trap.

More from MorningOverview