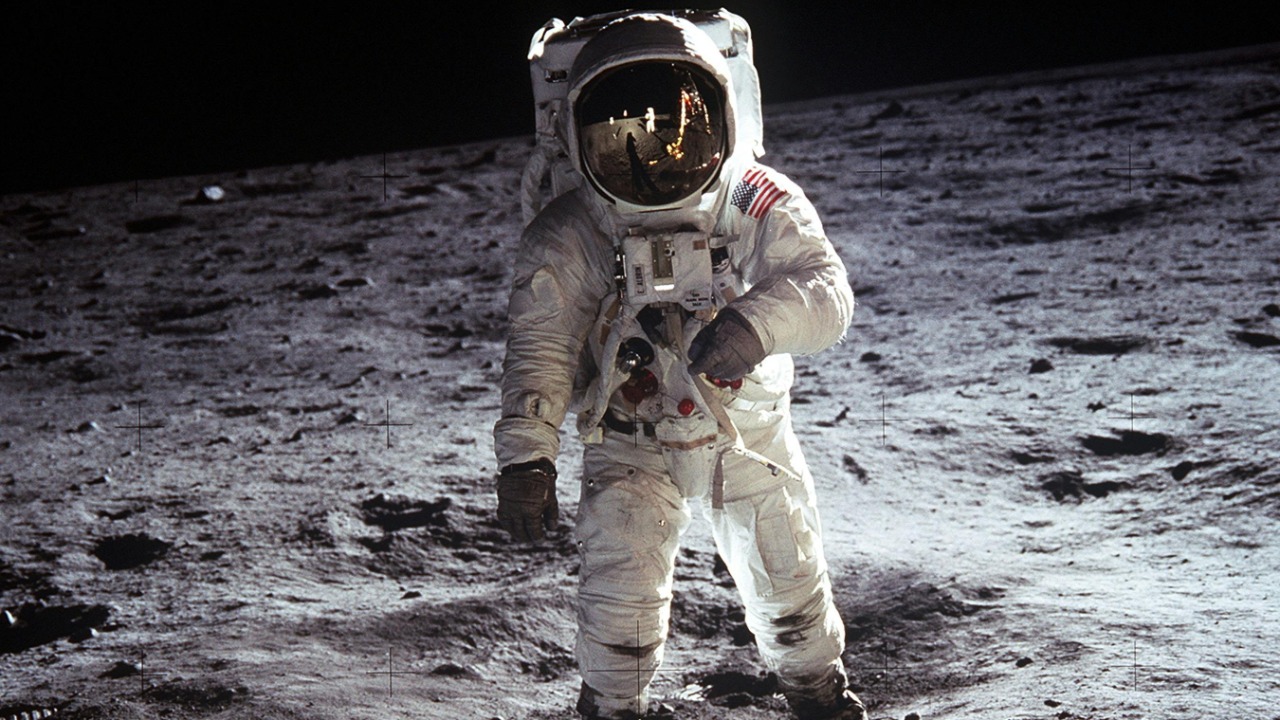

The Moon landing is often remembered as a daring gamble, a moment when human courage somehow outran the limits of 1960s technology. In reality, Apollo was less a lucky throw of the dice than a disciplined bet on a specific technological leap: turning guidance, navigation, and control into a fully digital problem. That decision, and the hardware and software it forced into existence, reshaped computing, engineering practice, and even how I think about modern reliability.

What made Apollo possible was not a single rocket or a single computer, but a system built around new silicon chips, new software methods, and new ways of managing risk. The program fused the Saturn V, the Apollo Guidance Computer, and a culture of systems engineering into a coherent whole that could land people on the Moon and bring them home with a level of precision that had never existed before.

The real breakthrough: turning guidance into a computer problem

When I look at the technical history of Apollo, the pivotal move was deciding that guidance and navigation would be handled by a compact, fully digital computer instead of analog boxes and human intuition. Earlier spacecraft had relied on a patchwork of mechanical and analog systems, but the Apollo teams chose to centralize control in what became the Apollo Guidance Computer, or AGC, and to treat the entire flight profile as a software driven problem. That choice forced engineers to define every phase of the mission in code, from translunar injection to the final descent to the lunar surface.

Accounts of how MIT shaped the Apollo missions describe how computer scientists and engineers at the MIT Instrumentation Laboratory had to invent practical digital flight control almost from scratch. They were not just wiring up a calculator, they were encoding the physics of orbital mechanics and the choreography of docking and landing into a machine that astronauts could trust with their lives. The result was a guidance system that turned an “impossible” mission into a sequence of deterministic steps, each one checked, simulated, and rehearsed long before the Saturn V ever left the pad.

MIT’s Instrumentation Laboratory and the birth of the Apollo Guidance Computer

The center of this transformation sat in Cambridge, where the MIT Instrumentation Laboratory took on a NASA contract to build the AGC for both the command module and the lunar module. In the 1960s, that lab was already known for precision control systems, but the Apollo work demanded a leap into integrated digital computing that had never been attempted in a spacecraft. Engineers had to design a compact, rugged computer that could survive launch vibrations, radiation, and temperature swings while still running complex guidance algorithms in real time.

Recollections from those who worked there describe how In the 1960s, the MIT Instrumentation Laboratory and NASA built the Apollo Guidance Computer as a shared effort, with hardware and software teams learning to think as one system. The AGC had to be small enough to fit in cramped cabins, yet powerful enough to integrate sensor data, execute guidance equations, and drive displays that astronauts could interpret under pressure. That collaboration between MIT and NASA did more than deliver a working computer, it created a template for how universities, government, and industry could co develop high risk technology.

Silicon chips, core memory, and the physical limits of 1960s computing

The AGC was one of the first major projects to bet heavily on integrated circuits, and that decision is where Apollo’s “luck” looks most like calculated risk. As the Apollo program took form, NASA engineers insisted on using silicon chips to shrink the computer and improve reliability, even though the technology was still new and expensive. That choice drove demand for mass produced integrated circuits and pushed suppliers to improve yields, effectively accelerating the entire semiconductor industry.

Historical accounts of the Apollo Guidance Computer and the first silicon chips explain how As the Apollo program took form in the early 1960s, NASA and its contractors had to rely on a poll of manufacturers and aggressive procurement to secure enough reliable components. At the same time, the AGC’s non volatile memory used magnetic cores woven by hand, with copper wires threaded through tiny ferrite rings. Later descriptions of this work note that TIL Non volatile memory onboard the Apollo spacecraft were made by manually weaving copper wires between magnetic cores, which meant that once the program was “rope loaded,” revisions to code were effectively impossible without rebuilding the hardware. That physical constraint forced an extraordinary level of discipline in software design and testing.

The DSKY interface and the leap in human computer interaction

Even the best guidance computer would have been useless if astronauts could not understand or control it under stress, which is where the DSKY interface became another quiet revolution. The DSKY, short for “display and keyboard,” translated the AGC’s internal state into a set of numeric codes and indicator lights that crews could read at a glance. Instead of flipping dozens of analog switches, astronauts interacted with the computer through verb noun commands, a structured language that mapped human intent to machine operations.

Technical retrospectives describe how They, NASA, MIT, Instrumentation Lab decided to go with a completely digital system, something that had not been done before in crewed spacecraft. The DSKY sat at the center of that system, giving astronauts a way to monitor guidance programs, enter corrections, and even recover from alarms during the lunar descent. In practice, this was an early form of human computer interaction design, where the interface had to be simple enough to use in seconds yet expressive enough to control a mission that spanned hundreds of thousands of kilometers.

From ad hoc coding to “Software Engineering The Apollo”

The software that ran on the AGC did not just appear as a side project, it forced the birth of modern software engineering practices. The scale and criticality of the code meant that informal programming habits were no longer acceptable, so teams had to invent methods for requirements tracking, version control, and systematic testing. In effect, Apollo turned software from a craft into an engineering discipline, with documentation, reviews, and formal processes that mirrored hardware design.Educational material on the history of computing notes that Software Engineering The Apollo missions were marked by their heavy use of computers, especially the Apollo Guidance Computer developed for the lunar missions. That emphasis on process did not eliminate risk, but it did create a culture where bugs were treated as systemic issues to be rooted out, not just patched. The rigor that emerged from this work still echoes in how safety critical systems are built today, from fly by wire airliners to medical devices.

Saturn V, “Sophisticated” systems, and the scale of the hardware challenge

None of this software would have mattered without a launch vehicle capable of lifting the spacecraft out of Earth’s gravity well, and the Saturn V was itself a technological leap. The rocket’s three stages, clustered engines, and massive fuel loads represented an engineering feat that had to be integrated with the guidance system from the start. The AGC did not just steer a capsule, it had to command a stack that included the command module, service module, and lunar module, all riding atop the most powerful launch vehicle ever built at the time.

Technical histories of the Saturn and the Apollo 11 launch vehicle that carried astronauts to the Moon emphasize how tightly coupled the rocket and spacecraft were. Broader analyses of complex systems point out that Sophisticated guidance systems, electronic computers, rockets, and radars pushed engineers beyond what traditional trial and error could handle. Instead, they had to rely on modeling, simulation, and telemetry driven feedback to validate designs before flight, a mindset that now underpins everything from cloud reliability engineering to autonomous vehicles.

Human stories: “Forty” years on, the people behind the code and circuits

It is easy to talk about Apollo in terms of hardware and software, but the program was also a human story of people who found their lives reshaped by the work. Engineers who joined MIT as young graduates found themselves responsible for code that would decide whether astronauts lived or died, a level of responsibility that left a lasting mark. Decades later, many of them still describe the experience as the defining chapter of their careers, not because of the fame of Apollo, but because of the intensity of the collaboration.

Personal recollections from MIT note that Jul, MIT, Apollo, Forty years after the first landing, veterans of the program still saw how that day changed their lives forever. Their stories underline how the technological leap was inseparable from a cultural one, where young scientists, programmers, and technicians were trusted with unprecedented responsibility. That trust, backed by rigorous review and testing, is part of why the mission’s success feels less like luck and more like the outcome of a deliberate, if risky, bet on human capability.

From “One Giant Leap” to everyday tech: spinoffs and lasting influence

When I trace Apollo’s legacy forward, the most striking thing is how much of today’s technology landscape carries its fingerprints. The digital flight control that kept the lunar module stable has clear descendants in modern airliners, reusable rockets, and even the stability systems in consumer drones. The discipline around software and systems integration that emerged from the program now shapes how we build everything from smartphones to industrial robots.

NASA’s own retrospectives point out that Jul, Here, Apollo, Moon, Digital Flight control technologies are among a small selection of Apollo innovations still in use 50 years after the first Moon landing. Writers like Michael Shermer and Charles Fishman have argued in public talks that the mission’s impact went far beyond flags and footprints, with Michael Shermer and Charles Fishman discussing One Giant Leap, Impossible Mission, Flew Us as a story of how a national project can rewire an entire industrial base. In another talk, Sep, Charles Fisherman, One Giant Leap the author revisits how the program’s tight deadlines and unforgiving requirements forced breakthroughs that later became mundane parts of daily life.

Apollo as a template for high stakes engineering today

Looking at modern complex systems, from internet scale services to crewed spacecraft heading back to the Moon, I see Apollo less as a nostalgic achievement and more as an early template. The program showed that when the problem is too complex for intuition, the only viable path is to formalize it into models, software, and feedback loops that can be tested and refined. That mindset is now standard in fields like site reliability engineering, where teams treat failures as data and design for graceful degradation rather than hoping for perfection.

Analyses of the broader Apollo era note that The Apollo missions and program spurred unprecedented advances in aerospace technology, From the de tails of materials science to the rigorous demands of the lunar missions. Even popular retrospectives, such as the On This Day, Space, Video Series that recalls how the giant Saturn rocket was the only launch vehicle capable of sending humans to the Moon, underline how singular the achievement was. The lesson I draw is that Apollo was not a lucky break in history, it was a proof that when you align bold goals with disciplined technology development, you can move the frontier of what is possible in a single decade.

More from MorningOverview