Physicists have finally turned a long standing thought experiment into a laboratory reality, showing that electromagnetic waves can be reflected in time as cleanly as light bounces off a mirror in space. Instead of watching a beam reverse direction, researchers are now watching signals flip their temporal order and jump to new frequencies, a result that forces a rethink of how rigid the flow of time really is in physical systems. The effect, once dismissed as too subtle to capture, is now being engineered on demand in carefully designed materials.

By creating these so called time mirrors, teams working in photonics and metamaterials have opened a new frontier for controlling waves, with implications that stretch from ultra secure communications to radically efficient computing hardware. What once lived only in equations is now a tunable device on a lab bench, and the race has begun to turn this strange control over time into practical technology.

From wild idea to laboratory reality

For decades, time reflection sat in the margins of theoretical physics, a mathematical curiosity that emerged when researchers played with equations describing how waves evolve. The basic prediction was simple but unsettling: if a medium changed its properties fast enough and uniformly enough, an incoming wave would not just scatter, it would reverse its temporal profile, as if the movie of its life had been run backward. That prediction lingered without proof because no one had a clear way to flip a material’s properties everywhere at once, which is what the equations demanded.

That impasse finally broke when researchers at the Advanced Science Research Center at the CUNY Graduate Center realized they did not need a cosmic event to test the idea, only a carefully engineered structure that could be switched extremely quickly. In a paper in Nature Physics, a team at the Advanced Science Research Center at CUNY described how they observed time reflections of electromagnetic signals in a tailored metamaterial, turning a long standing prediction into a measured effect. That breakthrough set the stage for a wave of follow up work that now treats time interfaces as a new kind of optical component rather than a theoretical oddity.

What a time mirror actually does to a wave

At its core, a time mirror is not a portal or a science fiction device, it is a very specific way of reshaping a signal. When a wave hits an ordinary mirror, its spatial direction reverses while its sequence of peaks and troughs stays in the same order. In a time mirror, the opposite happens: the wave keeps moving forward through space, but its temporal pattern is flipped, so the last part of the signal becomes the first, and the first becomes the last. The result is a time reversed copy of the original signal, still traveling outward but carrying a scrambled chronology.

One way to picture this is to imagine a sound clip that says “one, two, three” being transformed into “three, two, one” without ever bouncing off a wall. Reporting on the new experiments describes a time mirror as a device that takes an incoming disturbance and sends back a signal flipped backwards in time, while also shifting it to a different frequency band. That dual action, reversal plus frequency conversion, is what makes time mirrors so powerful for communications and sensing, because it lets engineers reshape when and where information lives in a spectrum.

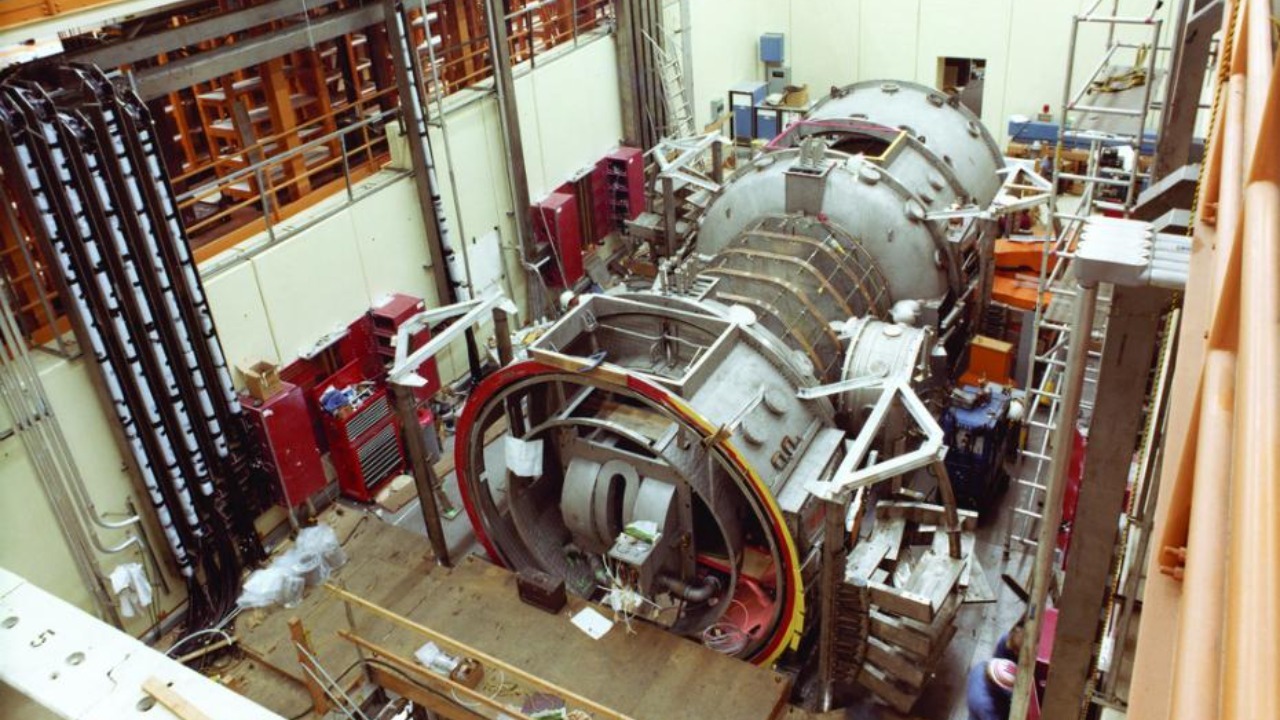

How CUNY’s metamaterial finally cracked the problem

The first clear demonstration of time reflection in electromagnetic waves came from a deceptively simple looking setup built around a metamaterial, a structure whose properties are engineered rather than found in nature. Researchers at the Advanced Science Research Center at CUNY created a medium whose effective electrical characteristics could be switched extremely quickly, then injected broadband signals into it to see how they responded. The key was to change the medium’s properties everywhere at once, fast enough that the wave could not simply adapt smoothly, forcing a sudden temporal discontinuity instead.

In their description of the work, the team explained that they used engineered metamaterials and injected broadband signals into a medium whose properties they could modulate in time, creating the conditions for a time interface. By carefully timing the switch, they saw part of the incoming energy convert into a new wave whose temporal profile was reversed and whose frequency content was shifted, exactly as theory predicted. That result did not just confirm the effect, it showed that time reflection could be dialed in and out like any other material response.

Inside the “groundbreaking experiment” that made time reflections visible

The experiment that first captured global attention was described as a “groundbreaking” demonstration of time reflection in a controlled electromagnetic system. The researchers did not rely on exotic particles or astronomical events, they built a device that could be fabricated and tested repeatedly, which is crucial if time mirrors are ever to leave the lab. They sent a well characterized signal through their metamaterial, triggered a rapid change in its properties, and then measured what came out with high precision instruments that could resolve both timing and frequency.

According to the detailed account of the setup, the team’s work, titled Scientists Demonstrate Time Reflection of Electromagnetic Waves, showed that part of the original signal was converted to a new frequency while its temporal order was inverted. They emphasized that this was not a small perturbation but a clear, measurable copy of the original waveform, now running backward in time. That clarity is what convinced many skeptics that time mirrors were no longer just a theoretical construct but a practical tool.

From electromagnetic signals to time reflected light

Once time reflection had been demonstrated for radio frequency electromagnetic waves, the obvious next step was to push the effect into the optical regime, where photons carry information in fiber networks and photonic chips. That transition is not trivial, because light oscillates far faster than radio waves, which means the medium must be switched even more quickly to create a sharp temporal interface. Nonetheless, photonics researchers have begun to adapt the same principles, designing materials and circuits that can be jolted into a new state in fractions of a trillionth of a second.

Work highlighted in a photonics study observing time reflected light waves describes how researchers have now seen the same kind of temporal reversal in optical systems that had been predicted for more than 60 years. By rapidly modulating the refractive index of a medium through which light was passing, they were able to generate a time reflected component of the optical wave, confirming that the effect is not limited to lower frequency signals. That extension into photonics is critical, because it connects time mirrors directly to the technologies that underpin modern communications and computing.

Why the Advanced Science Research Center became the epicenter

The Advanced Science Research Center at the CUNY Graduate Center has emerged as a focal point for this work because it brings together expertise in metamaterials, photonics, and theoretical physics under one roof. The same group that first reported time reflections in electromagnetic signals has continued to refine their devices, exploring how different material designs and switching protocols change the strength and clarity of the effect. Their laboratories are equipped to generate precisely shaped broadband pulses and to measure subtle changes in frequency and phase, which is exactly what time mirror experiments demand.

Coverage of their early results noted that scientists at the Advanced Science Research Center at the CUNY Graduate Center were “stunned” to see time reflections of electromagnetic signals, because the effect had been considered too delicate to observe in a noisy, real world environment. They reported that the sudden change in the medium’s properties caused the signals to reverse their temporal order and shift frequency during such an event, exactly as the models had suggested. That combination of surprise and confirmation has helped turn the center into a hub for collaborations on time interfaces and related phenomena.

Decades of speculation give way to confirmation

The recent wave of experiments did not appear out of nowhere, it capped more than half a century of speculation about whether time reversal symmetry could be harnessed in practical devices. Theoretical work in wave physics had long suggested that if a medium could be switched quickly enough, a time interface would form, but the engineering challenge of flipping a material’s properties uniformly in time kept the idea on the sidelines. As electronics and photonics matured, however, the ability to drive materials with intense, precisely timed pulses made it possible to revisit those old predictions with new tools.

Recent reporting describes how, after decades of speculation, physicists finally confirm the existence of time mirrors by creating a time interface that flips electromagnetic waves. Those accounts emphasize that the experiments did not just hint at the effect, they showed a robust, repeatable transformation that matched the theoretical description of a time mirror. The phrase “creating a time interface” has now become a term of art in the field, signaling that researchers are no longer content to talk about time symmetry in the abstract, they are building it into hardware.

How a time interface actually works inside the material

To understand what is happening inside these devices, it helps to think of a time interface as the temporal cousin of a boundary between glass and air. In space, when a wave crosses such a boundary, part of it reflects and part transmits, with the details set by the contrast in material properties. In time, when the properties of a single medium change abruptly everywhere at once, the wave experiences a similar kind of mismatch, but now the reflection happens in the time domain rather than in space. The wave cannot instantly adjust to the new conditions, so it splits into components that carry the imprint of both the old and new states.

Accounts of the experiments explain that the researchers achieved this by driving their metamaterial with a strong, fast control signal that changed its effective parameters in a tiny fraction of the wave’s period. One description notes that they injected broadband signals into a medium whose properties could be modulated, and that a postdoctoral researcher at CUNY ASRC helped design the switching scheme that produced a clean time reflection. The sudden change caused part of the signal to become a time reversed copy at a new frequency, while the rest continued forward in its original form, giving experimenters a direct handle on how energy is partitioned at a time boundary.

What time mirrors could mean for communications and computing

Once time mirrors can be built reliably, they become a new kind of component for managing information, with potential uses that go far beyond proving a point about fundamental physics. In communications, a device that can reverse and frequency shift a signal on demand could help clean up interference, compress data streams, or route information between different bands of the spectrum without the usual losses. Because the time reversed copy carries a scrambled chronology, it could also be used as part of encryption schemes or as a way to probe a channel’s properties by sending in a known pattern and analyzing its reversed echo.The same control over temporal order could be transformative for computing architectures that rely on waves rather than electrons, such as optical or microwave based processors. The original metamaterial experiment was framed as laying the foundations for revolutionary applications in wireless communications and optical computers, because time interfaces allow engineers to manipulate signals in ways that are hard to achieve with conventional filters and modulators. By integrating time mirrors into photonic circuits, designers could build logic elements that operate on the history of a signal, not just its instantaneous value, opening the door to new forms of analog computing and signal processing.

Why physicists describe the effect as “impossible” and “astonishing”

Part of the public fascination with time mirrors comes from the language physicists themselves have used to describe their first encounters with the effect. Researchers who had spent their careers working with waves in static or slowly varying media suddenly found themselves looking at data that seemed to show a signal running backward in time, a result that felt almost like a violation of causality even though it was fully consistent with the equations. That emotional jolt has colored the way the experiments are discussed, with words like “impossible” and “astonishing” appearing alongside the technical details.

One account describes how scientists confirm the impossible by showing that time reflections are real, shattering what many had assumed were firm boundaries in physics and human understanding. Another narrative, written in a more reflective style, talks about the astonishing presence of time mirrors and how comprehending time mirrors requires rethinking familiar cause and effect within the system. Those reactions underscore that even seasoned experts are still adjusting to the idea that time can be manipulated in the lab as flexibly as space.

Limits, open questions, and what comes next

For all the excitement, time mirrors are still in their infancy, and the current devices come with significant constraints. The effect depends on switching the medium’s properties extremely quickly and uniformly, which is easier to do in small, carefully controlled samples than in large, practical systems. There are also questions about how efficiently energy can be converted into the time reversed component, how robust the effect is to noise and imperfections, and how it behaves when multiple waves interact in complex ways inside the same material. Some reports emphasize that the sudden change in the medium’s properties is what makes the effect both powerful and hard to achieve, noting that this sudden change caused the signals to carry a time reversed copy, but that the need for such a rapid, uniform switch is part of what has made studying the concept so difficult. As researchers refine their metamaterials and photonic platforms, they will be looking for ways to relax those constraints, perhaps by using resonant structures or nonlinear effects to amplify the time reflection without demanding ever faster control pulses. The field is now moving from proof of principle to optimization, and the next few years will determine whether time mirrors become niche laboratory curiosities or standard tools in the wave engineer’s kit.

More from MorningOverview