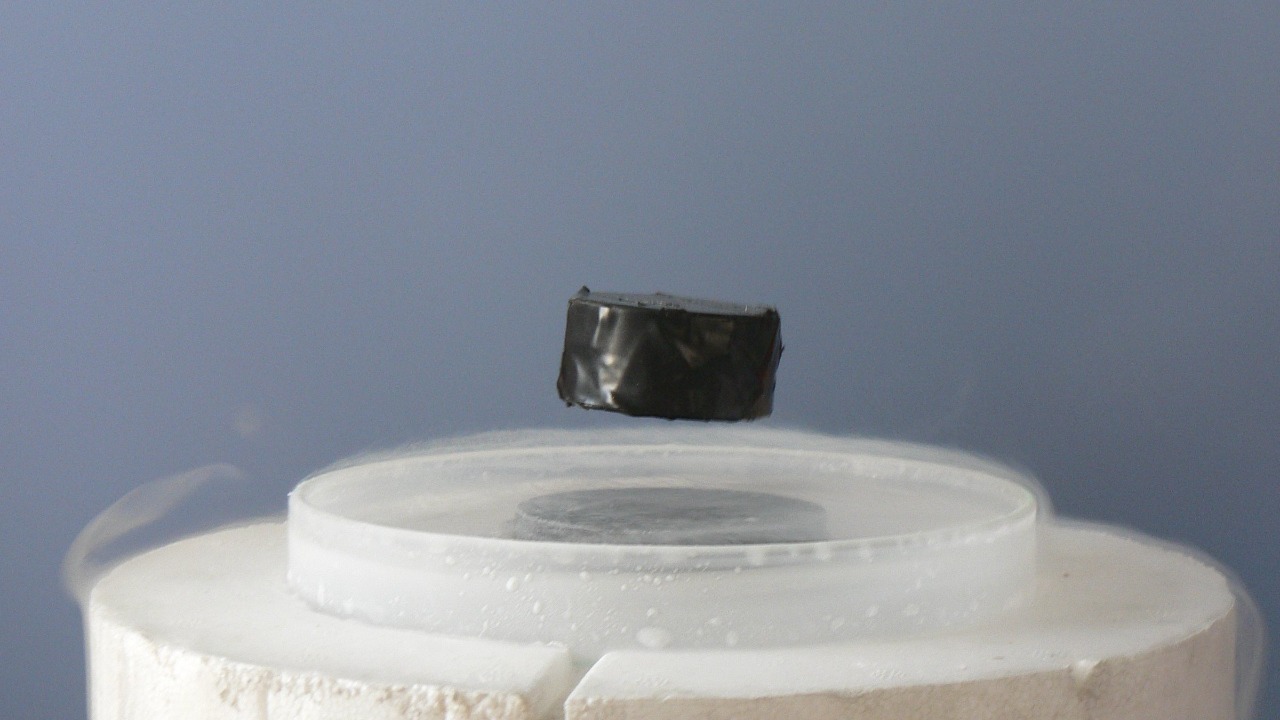

Physicists have spent decades building a tidy set of rules for how superconductors should behave, only to watch a new material tear through that rulebook. In ultra-clean, atomically thin carbon structures, electrons are pairing up in a Never-Before-Seen Pattern of Electron Pairing that fuses superconductivity with magnetism and other exotic quantum states. The result is a superconductor that not only carries current with zero resistance, but also behaves like a tiny magnet and shrugs off magnetic fields that should destroy it.

What makes this discovery so striking is not just that it adds another entry to the catalog of strange materials, but that it exposes gaps in the basic theory that underpins everything from MRI scanners to quantum computers. I see it as a stress test for the standard picture of electron pairing, one that forces researchers to rethink how electrons organize themselves in two-dimensional lattices and how those hidden patterns might be harnessed for more robust qubits and nanoscale devices.

Inside the superconductor that broke the rules

At the heart of the surprise is a layered carbon system where electrons refuse to follow the conventional script. Instead of forming the usual spin-singlet Cooper pairs that quietly cancel out their magnetic moments, measurements reveal a Never-Before-Seen Pattern of Electron Pairing that leaves a net magnetization intact. In other words, something unexpected is happening inside this material: it conducts electricity with zero resistance while simultaneously hosting a robust internal magnetic order that standard textbooks say should disrupt superconductivity, a contradiction highlighted in detailed spectroscopy of this new superconductor.

What makes this pattern so disruptive for theory is that it cannot be captured by simply tweaking existing models of electron pairing. The data point to a pairing state that is spatially anisotropic and intertwined with magnetism, rather than merely coexisting with it in separate regions. A companion analysis of the same system describes this as a Dec, Never, Before, Seen Pattern of Electron Pairing, emphasizing that the symmetry of the pairs and their response to magnetic fields do not match any of the standard categories used to classify superconductors, a conclusion reinforced by high resolution probes of the electron pairing pattern.

Why superconductivity and magnetism should not get along

To understand why this material is so unsettling, it helps to recall how ordinary superconductors work. In the classic picture, electrons form Coope pairs with opposite spins and momenta, creating a collective quantum state that flows without resistance. These spin-singlet pairs are fragile in the presence of strong magnetic fields, which tend to align the spins and rip the pairs apart, a limitation that usually defines whether a material is spin-singlet or spin-triplet and sets the critical field beyond which superconductivity collapses, as summarized in discussions of how superconductors behave in strong magnetic fields.

Magnetism itself is rooted in the same microscopic ingredients, the spin and orbital motion of electrons. All the electrons do produce a magnetic field as they spin and orbit the nucleus, and when two electrons in an atom have opposite spins, their magnetic fields cancel, while unpaired spins add up to a net magnetic moment that determines the direction of the magnetic field. In most superconductors, pairing electrons into singlets effectively wipes out these local moments, which is why long range magnetism and superconductivity are usually seen as competing orders, a tension that is central to basic explanations of electron pairing and magnetism.

The magnetic superconductor hiding in rhombohedral graphene

The new material that has captured so much attention is built from rhombohedral graphene, a carefully stacked form of carbon where each layer is slightly offset from the one below. In this structure, electrons move in a flat energy landscape that amplifies interactions, making it an ideal playground for unconventional phases. Researchers report that in this setting, superconductivity emerges alongside a clear magnetic signal, indicating that the same electrons responsible for zero resistance are also generating a net magnetic moment, a combination that points to a new form of magnetic superconductor described in a detailed Physics Journal report on rhombohedral graphene.

What sets this system apart is that the magnetism is not a weak side effect, but a robust feature that survives across the superconducting phase. Theoretical modeling and imaging suggest that the pairing state may be spin-triplet, with electrons in each pair spinning in the same direction, which would naturally produce a magnetic moment instead of canceling it. That picture is consistent with the idea that the material hosts a Dec, Never, Before, Seen Pattern of Electron Pairing, where the symmetry of the pairs is locked to the underlying lattice in a way that stabilizes both superconductivity and magnetism, turning rhombohedral graphene into a platform where these two usually antagonistic orders reinforce each other.

How ultra thin materials twist the rules of quantum matter

The discovery does not stand alone, but fits into a broader pattern of strange behavior in ultra thin materials that has been emerging over the past few years. When researchers strip materials down to a single or few atomic layers, they often find that electrons organize themselves in ways that are impossible in bulk crystals, leading to unexpected superconducting phases, correlated insulators, and topological states. A recent study of atomically thin systems described a Superconducting Surprise, with Strange Behavior in Ultra, Thin Materials that showed how reducing thickness and tuning the environment can flip a material from an ordinary conductor into a superconductor with highly unusual properties relevant for quantum computing and nanoscale devices, a trend captured in work on strange behavior in ultra thin superconductors.

In this context, rhombohedral graphene is part of a family of engineered two dimensional systems where stacking, twisting, and gating can be used to sculpt the electronic landscape. By carefully controlling the number of layers and their relative orientation, researchers can create flat bands where kinetic energy is suppressed and interactions dominate, a recipe that seems to favor unconventional superconductivity. The fact that such a system can host a Dec, Never, Before, Seen Pattern of Electron Pairing suggests that ultra thin materials are not just a new platform for known physics, but a source of qualitatively new quantum states that challenge the standard classification of superconductors.

Twisted graphene and the rise of unconventional superconductivity

Evidence that graphene based systems can harbor unconventional superconductivity has been building steadily. In twisted stacks of 2-D carbon, where two graphene layers are rotated relative to each other at a magic angle, experiments have revealed a superconducting gap that behaves as expected for an unconventional superconductor with nodes in its energy gap. Simultaneously, the same devices show correlated insulating states and other signatures of strong interactions, indicating that the electrons are not simply forming the conventional s-wave pairs seen in classic superconductors, but instead are entering a more complex pairing regime, as detailed in measurements on twisted carbon graphene superconductors.

Earlier this year, MIT researchers reported key evidence of unconventional superconductivity in graphene based devices that were not limited to the original magic angle configuration. By probing the temperature and field dependence of the superconducting state, they identified features that point to a pairing mechanism driven by strong correlations and lattice effects, rather than the phonon mediated interactions that dominate in conventional materials. Their work emphasized that the graphene platform allows exotic properties to emerge when the band structure is carefully engineered, reinforcing the idea that the Dec, Never, Before, Seen Pattern of Electron Pairing in rhombohedral graphene is part of a larger landscape of unusual superconducting states, a conclusion supported by their observation of unconventional superconductivity in graphene.

Anyons, conflicting quantum states, and a new theoretical puzzle

The coexistence of superconductivity and magnetism in these systems has pushed theorists to consider more exotic quasiparticles. One emerging idea is that anyons, particles that are neither fermions nor bosons and that can appear in two dimensional systems, might play a role in stabilizing these conflicting orders. In some models, the superconducting state can be reinterpreted as a condensate of anyons whose braiding statistics naturally accommodate both charge transport and magnetic textures, offering a route to reconcile the observed Dec, Never, Before, Seen Pattern of Electron Pairing with the presence of robust magnetism.

Recent work has framed this as a case of Conflicting Quantum States, with a Coexistence of Superconductivity, Magnetism The hallmark of a broader class of materials that includes rhombohedral graphene and molybdenium ditelluride (MoTe2). In these systems, the same electrons appear to participate in both orders, rather than segregating into separate domains, which suggests that the underlying quantum state is more intricate than a simple superposition of two phases. That perspective is central to proposals that anyons and related topological excitations are responsible for the unexpected superconductivity, an idea explored in analyses of conflicting quantum states in magnetic superconductors.

Rethinking electron pairs: from classroom diagrams to quantum devices

For decades, students have learned to picture Cooper pairs as two electrons with opposite spins and momenta gliding through a crystal lattice in lockstep, a simple cartoon that captures the essence of conventional superconductivity. The new findings force a revision of that mental image. In rhombohedral graphene and related systems, You can think of the two electrons in a pair spinning clockwise, or counterclockwise, which corresponds to a magnet pointing up or down, a description that aligns more naturally with spin-triplet pairing where the pair carries a net magnetic moment instead of canceling it, as emphasized in explanations of how electron pairs behave in magnetic superconductors.

This shift in perspective has practical consequences for device design. If electron pairs can be engineered to have a built in magnetic orientation, then superconducting circuits could be designed to integrate memory and logic in the same material, or to host qubits that are less sensitive to external noise. The Dec, Never, Before, Seen Pattern of Electron Pairing observed in the new superconductor suggests that by tuning stacking order, carrier density, and external fields, it may be possible to sculpt the internal structure of the pairs themselves, turning what was once a fixed property of a material into a controllable design parameter for future quantum technologies.

Why this matters for quantum computing and beyond

The stakes of this discovery extend well beyond condensed matter theory. Superconducting qubits, which already power many of the most advanced quantum processors, rely on delicate Josephson junctions that are vulnerable to magnetic noise and material imperfections. A superconductor that naturally combines zero resistance with intrinsic magnetism and resilience to strong fields could enable qubits that are both more compact and more robust, reducing the overhead required for error correction and potentially allowing quantum processors to operate in more flexible environments, a prospect hinted at in discussions of how the new material could serve as a platform for future qubits in quantum computers.

Beyond quantum computing, the ability to host superconductivity and magnetism in the same material opens doors for spintronics, where information is carried by spin rather than charge, and for ultra sensitive sensors that exploit the interplay between magnetic fields and superconducting currents. I see the Dec, Never, Before, Seen Pattern of Electron Pairing as a sign that the design space for such devices is far larger than previously assumed, especially in ultra thin materials where stacking and twisting can be tuned with atomic precision. As researchers map out this new territory, the superconductor that behaves in ways physicists did not expect may turn out to be less an outlier and more the first clear example of a broader class of quantum materials waiting to be discovered.

More from MorningOverview