Diesel aircraft engines promise lower fuel burn and cheaper operating costs at a time when every gallon and every kilogram matter in the air. Yet as manufacturers push these powerplants into more cockpits, regulators, pilots and neighbors under the flight path are asking a sharper question: does the efficiency story hold up once safety, reliability and emissions are fully counted. I want to unpack that tension, weighing what we know about performance, fire risk and pollution against the unresolved concerns that still shadow this technology.

From early experiments to a cautious comeback

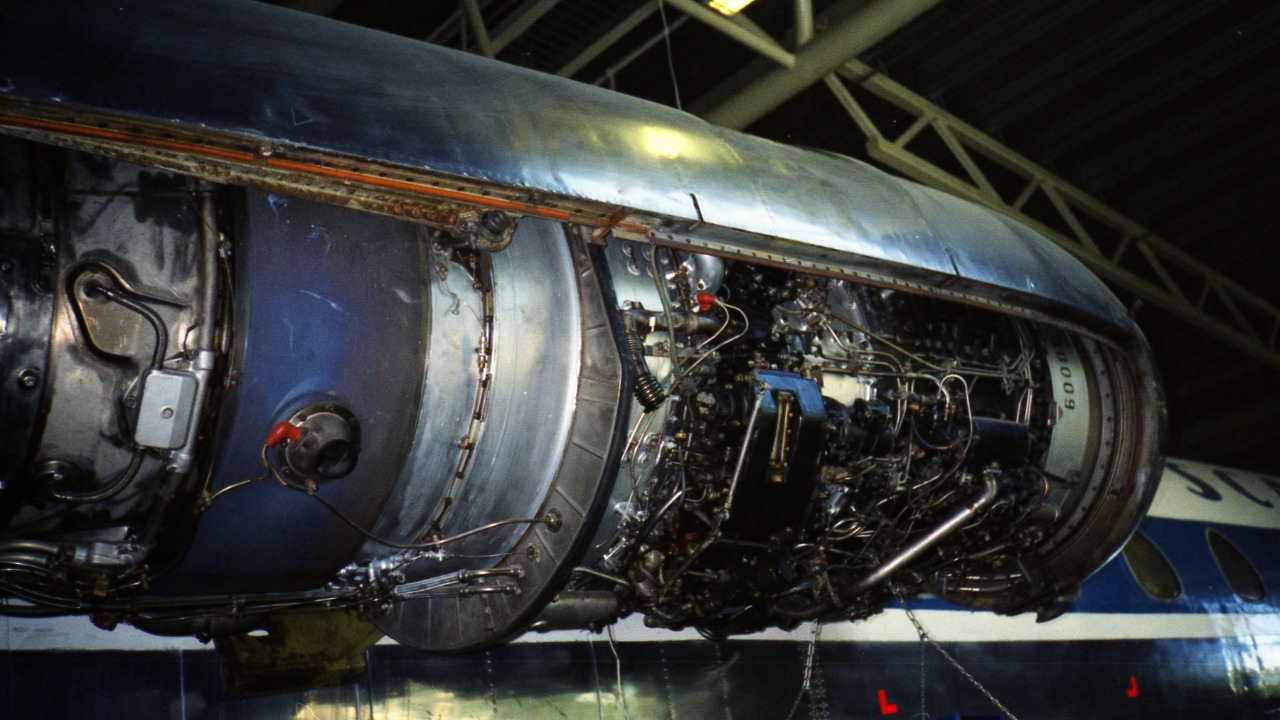

The idea of running Aircraft on compression ignition is not new, it is a revival. Engineers were experimenting with heavy fuel piston engines in the interwar years, attracted by their frugal consumption and ability to burn kerosene instead of volatile gasoline. According to historical overviews of the aircraft diesel engine, that first wave faded as lighter, simpler gasoline engines and then turbines took over, leaving only niche diesel projects on the drawing board.

The pendulum has swung back as fuel prices, climate pressure and leaded avgas phaseouts reshape general aviation economics. Modern designs use high pressure common rail injection and turbocharging to squeeze more work out of every kilogram of fuel, and several manufacturers have brought certified engines into production in the early 2010s and beyond. That history matters for safety, because it means today’s diesel aircraft engines are not untested novelties, but they also lack the many decades of fleet experience that conventional avgas engines have accumulated, which is why I see regulators and insurers still treating them with a degree of caution.

Why diesel looks so attractive on paper

On the spreadsheet, diesel powerplants are hard to ignore. Compression ignition typically delivers higher thermal efficiency than spark ignition, so for the same shaft horsepower a diesel burns less fuel, stretches range and frees up payload that would otherwise be locked in the tanks. Advocates point to Fuel Efficiency and Cost Savings, arguing that modern compression ignition engines often offer enhanced fuel economy and durability compared with legacy gasoline designs, especially when they can sip widely available Jet A instead of boutique 100LL.

Those efficiency gains are not just theoretical. Analyses of Diesel aircraft engines in light planes describe distinct advantages over gasoline engines, including better specific fuel consumption and the ability to use a fuel that is already stocked at most airports. For owners flying long cross country legs, that can translate into meaningful cost savings over the life of the engine, and for operators in remote regions, the flexibility to burn Jet A can be a logistical safety margin in itself when avgas supplies are patchy.

Reliability, torque and the propeller problem

Safety in aviation starts with whether the engine will keep turning, and diesel’s reputation in other sectors is a double edged sword. In the generator world, one of the main selling points is that a diesel unit is Pro, Reliable This, valued for long service life and the ability to run for extended periods under load. That same robustness appeals to aircraft designers who want engines that can handle high duty cycles without frequent overhauls, and it underpins the argument that diesel can enhance dispatch reliability for training fleets and commercial operators.

Yet the way diesel makes power creates its own engineering headaches. High compression ratios and abrupt combustion events generate strong torque pulses, and the use of propellers made of materials that do not easily absorb those pulses has often caused problems in matching powerplants to airframes. Technical notes on why some manufacturers still favor gasoline highlight that the use of propellers with limited torsional damping can lead to vibration, fatigue and even gearbox issues in a diesel powered aircraft. I see that as a reminder that reliability is not just about the core engine, but about the entire propulsion system and how it handles diesel’s different mechanical personality.

Fire risk and crash survivability

One of diesel’s strongest safety arguments has nothing to do with efficiency and everything to do with chemistry. Jet A and diesel have higher flash points than avgas, which makes them less prone to explosive ignition in a post crash scenario. Historical advocates of compression ignition in aviation framed this as FIRE HAZARD ELIMINATION, noting that the reduced volatility of heavy fuels can lower the risk of catastrophic fire when tanks rupture or lines are severed in an accident.

Contemporary engine makers echo that point. One manufacturer concludes on a positive note that diesel and Jet A1 fuel have a safety advantage that will always remain, because the fuel does not explode in the same way as gasoline in the case of an accident. That argument is reflected in guidance that describes Safer, Ending, Jet as a real benefit, even when other tradeoffs are acknowledged. From a risk management perspective, I see that as a compelling factor for flight schools and charter operators who worry about survivability as much as they do about fuel bills.

Environmental safety: efficiency versus toxic exhaust

Environmental groups are already scrutinizing how diesel fits into aviation’s climate and health footprint. On one hand, diesel fuel burns more efficiently than gasoline, which can reduce carbon dioxide per mile flown, but regulators warn that there is a price to pay in other pollutants. State level assessments of Diesel vehicles describe them as a principal source of nitrogen oxide, carbon monoxide and particulate matter, and those same combustion characteristics are relevant when the engine is bolted to a wing instead of a truck chassis.

Health agencies have gone further, warning that the microscopic soot and chemical mix in diesel exhaust can be significantly more harmful than gasoline fumes. One review of scientific research found that One study concluded diesel exhaust is 100 times more toxic than gasoline exhaust, and After reviewing multiple lines of evidence, the same report treated diesel exhaust as a known human carcinogen while classifying gasoline exhaust as a possible human carcinogen. When I weigh those numbers against the efficiency gains, it is clear that any safety conversation around diesel aircraft engines has to include the people breathing under approach paths, not just the pilots in the cockpit.

Noise, vibration and pilot workload

Noise is often treated as a nuisance issue, but in the cockpit it is also a safety factor that shapes fatigue and situational awareness. Diesel engines tend to operate at lower rpm with higher torque, which can change the sound profile and vibration transmitted through the airframe. Technical discussions of Since diesel engines produce much higher peak cylinder pressures, designers sometimes need heavier components and more robust mounts, and that can alter how vibration reaches the pilot and instruments.

From a workload perspective, modern diesel aircraft engines often integrate full authority digital engine control, which can simplify power management and reduce the risk of mixture mismanagement that has plagued some gasoline accidents. At the same time, the higher compression and different combustion dynamics mean that any misfire or fuel system issue can feel and sound different to a pilot trained on avgas engines. I see that as a training and human factors challenge rather than a showstopper, but it reinforces the idea that swapping fuels is not a plug and play change when safety margins are tight.

What the accident and performance record shows so far

Hard accident statistics for diesel powered Aircraft are still limited, but the performance record offers some clues about operational safety. Historical accounts note that before the Second World War there were a lot of diesel powered airplanes in service, and they required relatively very little maintenance compared with their gasoline peers. That experience is echoed in modern comparisons of But diesel and jet fuel use in different types of aircraft, which highlight the appeal of lower maintenance burdens for operators who log many hours per year.

Contemporary reporting paints a more mixed picture. Analyses of the Key Takeaways from the Aviation diesel push describe compelling economic and operational advantages, including better fuel efficiency and the ability to burn Jet A, but they also note that early adopters have faced teething issues with gearboxes, cooling and certification limits. More recently, industry coverage has reported that companies producing diesel airplane engines face questions about safety and performance, with the integration of diesel engines into aviation described as not without challenges and raising concerns about engine safety and performance. That scrutiny is captured in coverage that details how Dec developments have sharpened regulatory and customer focus on reliability metrics, not just fuel burn charts.

Modern designs and the promise of durability

Engine makers argue that the latest generation of diesel aircraft engines has learned from those early problems. One example is the compact V configuration promoted by DeltaHawk, which combines proven technologies with new innovations and modern materials to deliver a lighter, simpler package. Marketing material for the Diesel Airplane Engine emphasizes durability, reduced parts count and the ability to operate efficiently across a wide range of altitudes, all of which are framed as safety benefits because they reduce failure points and pilot workload.

Advocates also stress that diesel’s inherent torque and efficiency can support safer margins in marginal conditions. Analyses of Diesel, Gasoline, Technological Comparison highlight that the fundamental difference between diesel and gasoline engines lies in how they ignite fuel and manage compression, which in turn affects altitude performance, fuel sourcing options and detonation margins. In practical terms, that can mean more consistent climb rates on hot days and better resistance to misfueling, provided the aircraft is clearly placarded and pilots are trained on the differences.

Lead, Jet fuel and shifting definitions of “safe”

Any discussion of fuel safety in aviation now has to reckon with lead. Traditional 100LL avgas contains tetraethyl lead, and the “LL” simply means “low lead” rather than none, which has put piston aviation under growing regulatory and community pressure. Commentators comparing fuels note that Jet fuel is also much safer when it comes to the environment, because it does not contain lead, unlike 100LL, and that advantage is often cited alongside the cost savings that diesel engines offer. That perspective is captured in coverage that describes how Dec, Jet fuel’s lack of lead reshapes the safety calculus for communities near busy general aviation airports.

At the same time, environmental advocates point out that swapping lead for higher nitrogen oxide and particulate emissions is not a clean trade. Overviews of Aircraft, Please diesel engines note that while using diesel engines in aircraft can reduce some pollutants, the exhaust remains toxic as well as polluting, especially in the absence of automotive style aftertreatment systems. When I look at that balance, I see diesel as a step away from lead but not yet a destination that fully aligns with the health and climate goals many governments are now setting for aviation.

Where the safety debate goes next

For now, diesel aircraft engines sit in a liminal space between promising and proven. Economic arguments are strong, and the combination of lower fuel burn, Jet A availability and reduced fire risk gives them a compelling story in flight school brochures and fleet manager spreadsheets. Historical chapters on the FIRE and HAZARD ELIMINATION benefits of heavy fuel engines, combined with modern data on fuel efficiency, suggest that diesel can make some aspects of flying safer, especially in crash survivability and range planning.

Yet the unresolved questions are not trivial. Environmental research that treats diesel exhaust as 100 times more toxic than gasoline exhaust, the engineering challenges around torque pulses and propeller compatibility, and the relatively short modern track record of certified diesel aircraft engines all argue for humility. As more operators adopt these powerplants and as regulators gather better data on failures, emissions and community impacts, the industry will have to decide whether diesel is a bridge technology on the way to electric and hybrid propulsion or a long term pillar of general aviation. For now, I see the safest path as one that embraces diesel’s strengths while being honest about its limits, rather than assuming that efficiency alone can carry the weight of the safety case.

More from MorningOverview