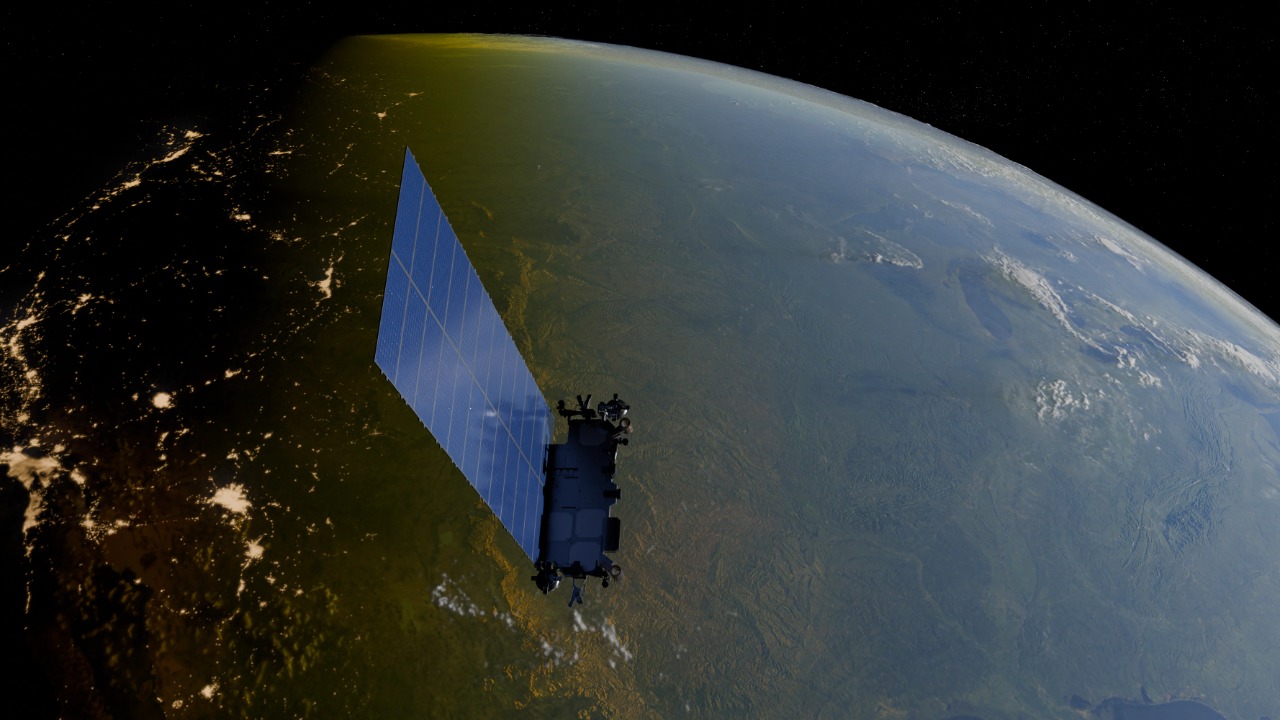

AST SpaceMobile has just vaulted the satellite telecom race into a new phase, lofting its largest spacecraft yet to support direct connections between orbit and ordinary smartphones. The BlueBird 6 satellite is not only a technical milestone, it is the clearest signal so far that Starlink will not have low Earth orbit to itself when it comes to space-based cellular coverage.

By pushing up the size, weight, and power of its latest platform, the company is betting that bigger hardware in low Earth orbit can translate into stronger signals for users on the ground and better economics for mobile operators. I see this launch as the moment the “Starlink rival” label starts to look less like marketing and more like a genuine competitive threat in the race to blanket the planet with broadband.

BlueBird 6: a record-breaking array aimed at your phone

BlueBird 6 is being framed as the largest commercial communications array yet deployed in low Earth orbit, a claim that underscores how aggressively AST SpaceMobile is scaling its hardware to reach standard handsets. The spacecraft rode to orbit on an ISRO LVM3 rocket lifting off at 10:25 p.m. EST from the Satish Dhawan Space Centre, a mission that placed the satellite into low Earth orbit to begin unfolding its enormous antenna structure and validate the company’s next-generation design for space-based cellular broadband. Company statements describe BlueBird 6 as part of a broader push to deliver universal mobile broadband connectivity, with the new satellite expected to demonstrate the full commercial configuration of AST’s direct-to-device architecture once its array is fully deployed and tested in orbit, building on earlier prototypes that proved the basic link between space and unmodified phones, according to largest commercial array.

The launch was also a symbolic moment for India’s space sector, pairing a high-profile American telecom payload with an Indian heavy-lift vehicle and ground infrastructure. AST SpaceMobile highlighted that BlueBird 6 reached orbit on a Tuesday flight from the Satish Dhawan Space Centre in India, reinforcing the role of ISRO’s LVM3 as a competitive option for commercial operators that need to place very heavy satellites into low Earth orbit rather than the traditional geostationary transfer orbit. The mission marked the first time AST has deployed one of its full-scale BlueBird satellites from Indian soil using an Indian launcher, a milestone that both the company and Indian officials have framed as a sign of growing collaboration between domestic launch providers and foreign constellation operators, as detailed in coverage of the AST mission from India.

From countdown tweet to orbital reality

AST SpaceMobile spent days building anticipation for BlueBird 6, using social channels to frame the launch as the start of a new phase in its quest to connect the unconnected. In a post tagged with “Dec” and “EST,” the company told followers that “The countdown begins!” and that BlueBird 6 was planned to launch on December 23, 2025 at 10:24 p.m. EST, describing the mission as the first step toward “cellular broadband connectivity for all.” That messaging was not just hype, it was a clear attempt to differentiate AST’s model from traditional satellite internet by emphasizing that the service is meant to talk directly to normal smartphones without any extra hardware, a promise that, if it holds up in commercial service, could be far more accessible than dishes or specialized terminals, as the company previewed in its Dec launch countdown.

Once the rocket cleared the pad, AST quickly moved from social media build-up to formal confirmation that BlueBird 6 was safely in orbit. In a detailed announcement, the company described the mission as the successful orbital launch of BlueBird 6, calling it the largest commercial communications array ever deployed in low Earth orbit and noting that liftoff occurred from the Satish Dhawan Space Centre in Sriharikota, India. The statement, timestamped in Eastern Standard Tim, underscored that the satellite had separated as planned and that early telemetry looked healthy, setting the stage for a deployment sequence that will see the spacecraft unfurl its massive antenna and begin on-orbit testing with partner mobile networks, according to the successful orbital launch.

India’s heavy-lift “Baahubali” and the heaviest commercial satellite to LEO

BlueBird 6 is not just big by AST’s internal standards, it is being described as a record-setter for commercial payloads to low Earth orbit. The satellite is part of the BlueBird Block‑2 line and weighs approximately 6,100 kg, a figure that makes it the Heaviest Commercial Satellite to LEO according to technical briefings that emphasize both its mass and its role in a planned constellation aimed at universal mobile broadband connectivity. That 6,100 kg figure is striking in a sector where many low Earth orbit satellites are measured in hundreds of kilograms, and it reflects AST’s decision to pack a very large phased array and high-power electronics into a single platform rather than relying solely on swarms of smaller spacecraft, as noted in analyses of the Heaviest Commercial Satellite.

For ISRO, carrying such a massive commercial payload was a showcase for its LVM3 rocket, sometimes nicknamed “Baahubali” for its lifting power. Reports on the mission stress that this is AST SpaceMobile Inc’s largest-ever satellite from India and the first in a series of deployments that will help the company build out its direct-to-cell constellation, with the LVM3 M6 flight framed as a challenge to SpaceX’s dominance in the commercial launch market. Indian coverage highlighted that the mission, flown for AST SpaceMobile Inc, underscores how India is positioning itself as a competitive provider for heavy commercial launches to low Earth orbit as well as to geostationary transfer orbit (GTO), according to ISRO, a point that was driven home in reporting on how the heaviest challenges SpaceX.

Why AST is betting on giant “Block 2” birds

The BlueBird 6 mission is also the first real-world outing for AST’s Block‑2 design philosophy, which leans into size and power rather than miniaturization. Technical notes on the program explain that the next-generation Block 2 BlueBirds are designed to deliver up to 10 times the bandwidth capacity of the earlier BlueBird satellites, a leap that is central to AST’s argument that it can support not just emergency text messaging but full-fledged broadband experiences for users on the ground. The company plans to place multiple Block‑2 spacecraft into low Earth orbit once launched, creating a mesh of very high capacity nodes that can hand off connections as the satellites pass overhead, according to specifications for the Block 2 BlueBirds.

That design choice sets AST apart from Starlink’s approach, which relies on thousands of smaller satellites to create dense coverage. By contrast, AST is effectively building a constellation of “cell towers in space,” each with a huge footprint and the ability to talk directly to standard 4G and 5G phones. The trade-off is that each Block‑2 satellite is far more complex and expensive to build and launch, but the payoff could be a network that integrates more seamlessly with terrestrial mobile infrastructure and offers carriers a way to extend their existing spectrum and billing systems into the sky without forcing customers to buy new hardware, a strategy that is central to AST’s pitch for its Starlink Rival Fires Back With Its Biggest Satellite Ever.

Direct-to-cell: how this differs from Starlink’s dish model

At the heart of AST SpaceMobile’s strategy is a technical and commercial bet that direct-to-cell connectivity will prove more attractive than satellite services that require dedicated terminals. Earlier briefings on the company’s technology describe it as a way for mobile carriers to serve users in cellular dead zones, ensuring a phone can reach a satellite in orbit when it cannot see a terrestrial tower, with the goal of letting customers keep their existing numbers and plans. The system is designed so that a standard smartphone, such as an iPhone or Android device, can connect to the satellite using the same radio bands it already supports, which is why AST has focused on building very large, sensitive arrays in low Earth orbit that can pick up those relatively weak handset signals, a capability outlined in descriptions of how the technology is designed.

Starlink, by contrast, has built its business around user terminals that look like small satellite dishes, which users must install at home or carry with them, a model that has proven popular in rural broadband but is less seamless for on-the-go smartphone users. AST’s pitch is that by integrating directly with mobile networks, it can make satellite coverage feel like a natural extension of existing service, with roaming onto space-based cells when needed and falling back to ground towers when available. That is why the company has been so aggressive in signing deals with carriers and in emphasizing that its satellites are meant to be invisible to the end user, who will simply see bars of coverage in places that used to be blank spots on the map, a vision that has been central to its positioning as Like Starlink, But For Mainstream Users.

Telecom’s space race: Verizon, T-Mobile and the carrier calculus

AST’s hardware only matters if mobile operators are willing to plug into it, and here the company has made notable progress despite delays and technical hurdles. In the United States, Verizon and AST initially announced a partnership that saw the telco agree to invest $100 million in the satellite company, a package that combined direct funding with commercial commitments to use AST’s network for space-based coverage. That deal was framed as part of a broader Telecom Space Race, with Verizon and AST positioning their alliance as a way to leapfrog rivals in offering satellite-backed coverage, even as the project timeline has been plagued with delays that pushed back the first commercial launches and forced AST to raise additional capital, according to reporting on how Telecom Space Race dynamics are unfolding.

AST has also courted other major carriers, including T-Mobile, which has separately partnered with SpaceX on a direct-to-cell initiative that would use Starlink satellites to connect phones in dead zones. Earlier coverage of AST’s plans noted that its technology was expected to begin serving T-Mobile customers in the fall once the first commercial satellites were in orbit, underscoring how carriers are hedging their bets by working with multiple satellite providers. For the operators, the calculus is straightforward: partnering with a company like AST offers a way to extend coverage without building expensive new towers in remote areas, while also giving them a story to tell regulators and customers about closing the digital divide, a narrative that has been central to the framing of AST as a Starlink rival in the mobile space.

A Starlink rival steps out of the shadow

For years, AST SpaceMobile has been described primarily in relation to Elon Musk’s satellite giant, but BlueBird 6 gives the company a chance to define itself on its own terms. Analysts have framed AST as operating in the same broad market as Starlink, with both companies racing to build broadband services via satellites, yet they stress that AST is targeting mainstream users who may never buy a dish or think of themselves as satellite customers. Commentary on the company’s prospects notes that there is an ongoing race to build broadband services via satellites, with Elon Musk’s Starlink dominating the early conversation, but that AST’s focus on direct-to-cell and partnerships with carriers could give it a differentiated value proposition if it can execute, a theme explored in assessments of why There is an ongoing race in orbit.

The BlueBird 6 launch has already been cast as a direct response to Starlink’s rapid expansion, with some coverage explicitly calling AST a Starlink rival that is firing back with its biggest satellite ever. That framing highlights how the competitive narrative is shifting from raw satellite counts to questions of capability, coverage, and integration with terrestrial networks. If AST can prove that a handful of very large satellites can deliver reliable, high-throughput connections to ordinary phones, it will not need to match Starlink’s constellation size to pose a serious challenge in certain segments, particularly in markets where regulators and carriers are wary of relying on a single provider for critical connectivity, a point underscored in reports that describe how a Starlink Rival Fires Back With Its Biggest Satellite Ever to deliver service directly to everyday smartphones.

The Giant in the Sky and the 2026 race for dominance

Market watchers have already dubbed BlueBird 6 “The Giant in the Sky,” a nickname that captures both its physical scale and its symbolic weight in the emerging direct-to-cell market. Analyses of the mission argue that the launch ignites the race for Direct-to-Cell Dominance in 2026, with AST SpaceMobile’s new hardware serving as a test case for whether large, high-capacity satellites can deliver on the promise of seamless coverage without overwhelming the company’s balance sheet. The final days of 2025 have seen AST’s stock trade against a backdrop of high expectations and a volatile investor base, reflecting both excitement about the potential upside and anxiety about execution risk, as highlighted in commentary that describes how The Giant in the Sky is reshaping expectations.

Looking ahead to 2026, the competitive landscape is likely to be defined less by individual launches and more by which companies can move from demonstration to dependable service. AST will need to show that BlueBird 6 and its Block‑2 siblings can maintain stable links, integrate cleanly with carrier networks, and scale up without crippling capital costs, all while Starlink and other players push their own direct-to-device offerings. If AST succeeds, the company will have validated a model in which a relatively small number of very capable satellites act as orbital extensions of terrestrial networks, potentially changing how regulators, carriers, and consumers think about coverage and making space-based cell service feel as ordinary as roaming onto a different ground network.

India’s launch pad to a new kind of connectivity

One of the quieter but significant storylines in the BlueBird 6 mission is India’s emergence as a key enabler of the direct-to-cell revolution. By launching AST’s largest-ever satellite from the Satish Dhawan Space Centre using an Indian rocket, ISRO has positioned itself as a partner of choice for companies that need to place very heavy, high-value payloads into low Earth orbit. Reports on the mission emphasize that an Indian rocket launches AST SpaceMobile’s next-gen BlueBird 6 satellite, with commentary from Jason Rainbow December noting that this is the first time AST has flown such a major spacecraft from Indian soil using an Indian launcher, a milestone that signals growing confidence in India’s ability to support complex commercial missions, as detailed in coverage of how an Indian rocket launches AST.

For India, these kinds of missions are about more than launch fees, they are a way to stake a claim in the broader ecosystem of space-enabled connectivity that will shape global telecom in the coming decade. As more companies pursue constellations aimed at everything from maritime tracking to Internet of Things devices and direct-to-cell service, launch capacity and reliability become strategic assets. By successfully delivering BlueBird 6, ISRO has shown that its LVM3 can handle some of the most demanding commercial payloads in the market, giving India leverage in negotiations with future constellation operators and reinforcing its status as a rising space power that can help define how, and by whom, the next billion users come online.

More from MorningOverview