When scientists finally cracked open the capsule from asteroid Bennu, they expected carbon, water-bearing minerals, and maybe a few familiar organic molecules. What they did not expect was a dense, glassy crust of sodium-rich phosphate, a material so unusual that several researchers described it as something they had “never seen before” in any meteorite collection. That surprise has rapidly shifted Bennu from a promising target into a kind of Rosetta stone for understanding how water, organics, and even the building blocks of life were assembled in the early solar system.

The Bennu samples are now revealing a chemically rich world that once hosted liquid water, complex organics, and even dust grains older than the Sun itself. As I trace the emerging picture from multiple research teams, the unpredicted phosphate material turns out to be the keystone that links Bennu’s watery past, its cargo of sugars and nucleobases, and a growing suspicion that this rubble pile may be a fragment of a long-lost ocean world.

From “ball pit” asteroid to pristine time capsule

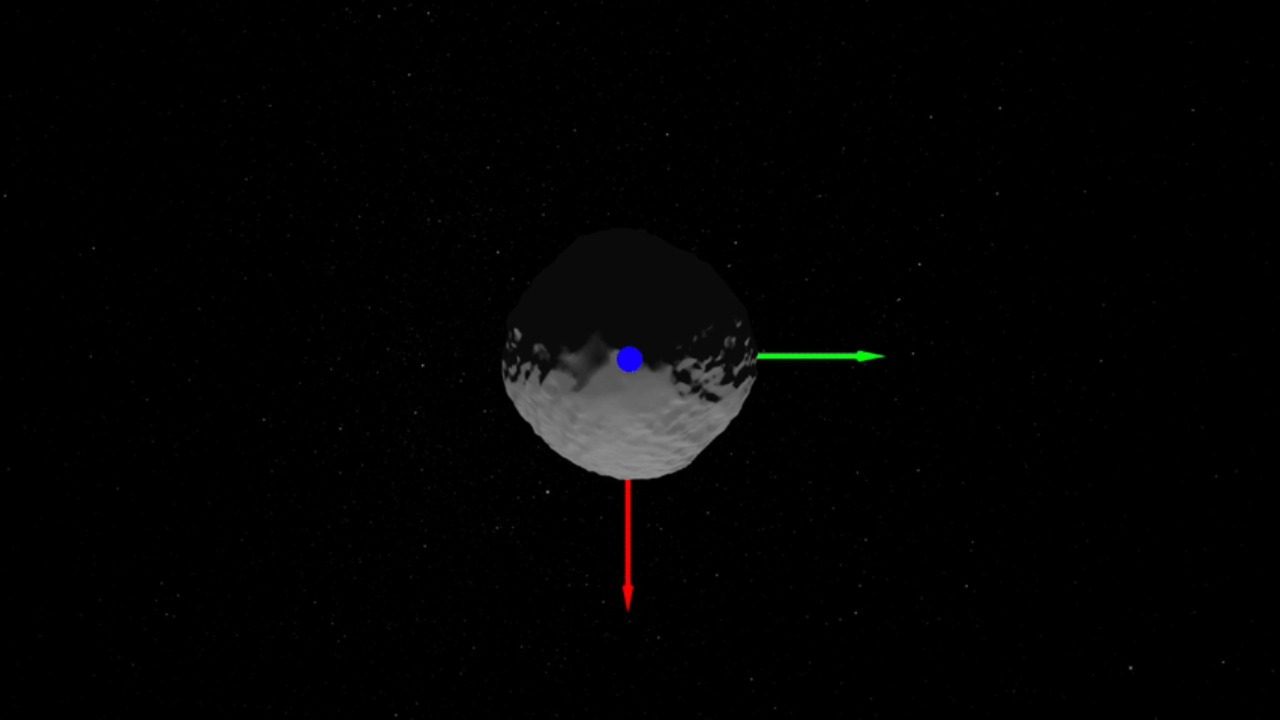

Long before anyone saw the sodium phosphate crust, Bennu had already earned a reputation for defying expectations. When NASA’s OSIRIS-REx spacecraft arrived and began its detailed survey, the team discovered that the surface was not a solid rock but a loose jumble of boulders that behaved like a “punching ball pit” under the sampling arm. That strange mechanical behavior hinted that Bennu’s interior was a fragile rubble pile, lightly held together by gravity and filled with voids, rather than a monolithic chunk of stone. It also meant that the material OSIRIS-REx would collect was likely to be extremely primitive, preserved in a low-pressure environment since the dawn of the solar system.

When the spacecraft finally touched down, the sampling head sank far deeper than engineers had planned, and later measurement of the forces on the probe confirmed just how insubstantial Bennu’s surface really was. That dramatic interaction, combined with the asteroid’s dark, carbon-rich spectrum, set expectations that the returned material would be rich in hydrated minerals and organics. Yet even in that context, no one anticipated that the first detailed look at the grains would reveal a crust of sodium-rich phosphate glass that appears to have formed in liquid water and then remained astonishingly unaltered for billions of years.

The shock of sodium-rich phosphate “glass”

The most striking surprise emerged during the Early analysis of the Bennu grains, when researchers spotted a bright, glassy coating dominated by sodium phosphate. In the lab, this material stood out immediately because it was both chemically simple and unusually pure, lacking the complex mixture of other elements that typically accompany phosphates in meteorites. The team described the phosphate as “unprecedented in any meteorite sample,” a strong statement from scientists who routinely handle some of the rarest rocks on Earth. Its very existence suggested that Bennu had experienced a specific kind of water-rich environment that allowed phosphate to dissolve, concentrate, and then crystallize or vitrify without being overprinted by later heating or alteration.

That finding dovetailed with another report from a researcher who recalled that When they first found sodium carbonate in a sample of Bennu at the Smithsonian, it was a mineral they had never seen before in their collections. Sodium carbonate and sodium phosphate both point to alkaline, carbonate-rich waters that can dissolve and transport phosphorus, then leave it behind as the water evaporates or cools. Together, these minerals paint a picture of Bennu’s parent body as a place where liquid water moved through rock in veins and pockets, concentrating key elements in ways that are highly relevant to prebiotic chemistry.

A watery past written in veins and pockets

The phosphate crust did not appear in isolation. Other teams examining Bennu’s rocks have reported clear evidence that water once flowed through its parent body, leaving behind hydrated minerals and chemical gradients. One researcher, Jan McCoy, has emphasized that this water “likely existed not on the surface, but as a vein or pocket under the surface of the asteroid,” where it could dissolve minerals and then deposit them as the fluid cooled or evaporated. That scenario is supported by the textures and compositions seen in the samples, which show signs of water-rock interaction in confined spaces rather than global oceans. The presence of these subsurface veins helps explain how sodium-rich phosphates and carbonates could accumulate in such high concentrations within relatively small regions of the rock.

Those same water-altered minerals are central to the argument that Bennu’s parent body was once much larger and warmer than the current 500-meter-wide rubble pile. Over the summer, one study suggested that the chemistry of Since the Bennu samples points to a world where liquid water was stable for extended periods, likely due to internal heating from radioactive decay. In that environment, water could circulate through fractures, leach elements like sodium and phosphorus from the rock, and then precipitate them as minerals when conditions changed. The sodium phosphate crust, in this view, is not an oddity but a frozen snapshot of a once-active hydrothermal system that operated deep inside a now-vanished body.

Hints Bennu came from an ocean world

As the phosphate story unfolded, another line of evidence began to push scientists toward an even bolder idea: Bennu might be a fragment of an ancient ocean world. One analysis of a millimeter-scale grain, described simply as This Bennu particle, found mineral assemblages that are difficult to reconcile with a small, cold asteroid. Instead, the chemistry suggested formation in a body with extensive water, possibly including a global or regional ocean beneath an icy crust. The sodium-rich phosphate and carbonate minerals fit naturally into that scenario, since they can form in alkaline, salty waters similar in some respects to Earth’s soda lakes or the subsurface oceans suspected on moons like Europa and Enceladus.

If Bennu is indeed a shard of such a world, then its samples offer a rare chance to study ocean chemistry from a time before Earth’s own earliest rocks were preserved. The idea is still being tested, but the combination of hydrated minerals, concentrated phosphates, and specific carbonate signatures has already led several researchers to argue that Bennu’s parent body was far more complex than a simple rubble pile. In that context, the sodium phosphate crust becomes a kind of smoking gun, a mineralogical clue that points back to a once-habitable environment where water, rock, and time conspired to create the ingredients for life long before any planet cooled enough to host biology on its surface.

Sugars, “gum,” and the chemistry of energy

The surprise phosphate material would be headline enough, but Bennu’s samples have also delivered a rich inventory of organic molecules that speak directly to life’s energy economy. Laboratory work has revealed that The Bennu grains contain one of the most common forms of “food” used by life on Earth, the sugar glucose, along with other bio-essential sugars. According to a detailed mission update, The Bennu samples also contained a sticky, polymer-like material described as “gum,” which may represent complex organic networks formed in space. On Earth, Glucose provides cells with energy and is used to make fibers like cellulose, so finding it in an asteroid sample underscores how far prebiotic chemistry can progress in the absence of biology.

Another team has highlighted that RNA uses ribose for its structure, and that the same suite of Bennu samples contains ribose alongside glucose and other sugars. In a mission briefing, scientists emphasized that RNA and Glucose are central to life’s information storage and energy metabolism, yet here they appear as products of non-biological chemistry in a small body orbiting the Sun. The presence of these sugars, together with the sodium phosphate crust, is particularly striking because phosphate groups and sugars are the backbone of both RNA and DNA. Bennu, in other words, is not just delivering isolated building blocks, it is delivering them in combinations that look eerily like the scaffolding of genetic molecules.

Nucleobases and the full alphabet of life

The sugar story is only one part of Bennu’s organic inventory. A separate set of analyses has reported that the samples contain all five nucleobases used in modern biology: adenine, guanine, cytosine, thymine, and uracil. One paper, published in the journal Nature Astronomy, described the discovery of these nucleobases in the Bennu samples as “tantalizing,” because it suggests that the full alphabet of genetic coding molecules can be assembled in space and delivered intact to planetary surfaces. On Earth, these nucleobases pair with sugars and phosphate groups to form the nucleotides that make up RNA and DNA, so finding them alongside ribose, glucose, and sodium phosphate in the same asteroid material is a powerful hint that prebiotic chemistry in space can reach a high level of complexity.

From a chemical perspective, the coexistence of nucleobases, sugars, and phosphates in Bennu’s rocks is significant because it reduces the number of independent steps that must occur on a young planet to assemble the first genetic polymers. Instead of having to synthesize each component from scratch, a world like the early Earth could receive a pre-mixed package of ingredients from bodies like Bennu. The fact that these molecules have survived for billions of years in a small, airless object also suggests that similar organics could be preserved in other primitive bodies, waiting to be sampled. In that sense, Bennu is not just a curiosity, it is a proof of concept that the raw materials for life’s information systems can be manufactured and stored in the cold reaches of space.

“Bennu tea” and the case for mobile phosphorus

To understand how accessible these ingredients might have been on Bennu’s parent body, researchers have gone beyond dry mineralogy and into experiments that mimic how water would interact with the rock. In one striking demonstration, a team prepared a hot water extract from an asteroid Bennu sample, informally dubbed “Bennu tea,” and found that the liquid contained a surprising abundance of dissolved phosphate and other ions. The result, illustrated in mission graphics, showed that a simple water soak could liberate large amounts of phosphorus from the rock, making it available for further chemistry. This experiment, captured in a set of Bennu visuals, reinforces the idea that subsurface veins and pockets of water on Bennu’s parent body could have been rich in dissolved phosphate, a key ingredient for energy-carrying molecules like ATP and for the backbones of RNA and DNA.

The mobility of phosphorus in these conditions is crucial because, on Earth, phosphate is often locked up in minerals that are not very soluble, limiting its availability for biological processes. Bennu’s sodium-rich phosphate glass and the “Bennu tea” experiment suggest a different regime, one in which alkaline waters can dissolve and transport phosphorus efficiently, then deposit it in concentrated forms as conditions change. That scenario aligns with the presence of sodium carbonate and other soluble salts in the samples, which point to a chemistry more akin to evaporating lakes than to dry, static rock. If similar processes were common in the early solar system, then many small bodies could have hosted transient environments where phosphorus cycled between rock and water, setting the stage for more complex prebiotic reactions.

Stardust older than the Sun

Beyond water and organics, Bennu’s samples contain another kind of surprise material that no one can truly “predict” in detail: presolar grains. These tiny particles, sometimes called Dust older than the solar system, formed in stars that predate the Sun and were later incorporated into the cloud of gas and dust that collapsed to form our planetary system. A third study focusing on these grains found that some material inside the samples is literally older than the solar system itself, preserving isotopic signatures of ancient stellar processes. The presence of such grains in Bennu was anticipated in broad terms, but their specific compositions and abundances are now providing fresh constraints on how material from different stellar sources was mixed in the early solar nebula.

These presolar grains sit side by side with the sodium phosphate glass, sugars, and nucleobases, creating a layered record that spans from distant stars to nascent oceans. One synthesis of the findings noted that some material inside the samples is so pristine that more surprises may show up as analytical techniques improve, a point underscored in a report on Dust and sugars in Bennu. For me, the juxtaposition is striking: grains forged in ancient stars are embedded in a matrix that later hosted liquid water and complex organics, all within a body that eventually broke apart and reassembled into the rubble pile we see today. Bennu is not just a time capsule, it is a palimpsest, with each layer of material recording a different chapter in the story of how matter in the universe becomes capable of supporting life.

Global teams and meticulous analysis

None of these insights would be possible without an enormous, coordinated effort to handle and study the Bennu material with extraordinary care. A team of scientists from across the globe has been working through the first in-depth analysis of the sample, documenting minerals in the asteroid that have never before been identified in any meteorite. According to a detailed institutional release, this work has already revealed that Bennu contains phases that speak to low-temperature water alteration, high-temperature processing, and everything in between. The same release emphasizes that the material was delivered to Earth (the Earth) in such a pristine state that even delicate minerals and organics have survived, giving researchers a rare chance to study them before they are altered by our planet’s environment.

Within this global effort, different labs have specialized in different techniques, from high-resolution imaging and spectroscopy to isotopic measurements and organic chemistry. The phosphate discovery, for example, relied on careful analysis of grain surfaces and cross sections, while the mechanical properties of Bennu’s surface were inferred from precise measurement of the forces on OSIRIS-REx during touchdown. Together, these methods are turning a few hundred grams of dark, dusty material into a detailed narrative about planetary formation, water circulation, and organic synthesis. The fact that so many “never seen before” minerals and textures are emerging from such a small sample underscores just how much of the solar system’s chemical diversity remains unexplored.

Rewriting expectations for life’s origins

As I weigh the different strands of evidence, the unpredicted sodium phosphate crust looks less like an oddity and more like a pivot point in our understanding of how habitable chemistry emerges. Phosphorus has long been a bottleneck in origin-of-life scenarios, often assumed to be scarce and poorly soluble in early planetary environments. Bennu’s sodium-rich phosphate glass, the “Bennu tea” experiment, and the coexistence of sugars, nucleobases, and carbonates all challenge that assumption. They suggest that in at least some small bodies, phosphorus could be both abundant and mobile, cycling through water-rich veins and precipitating in concentrated forms that are directly usable in prebiotic reactions. When I connect that picture to the possibility that Bennu’s parent body was an ocean world, the implications for the early Earth and for other planets become hard to ignore.

At the same time, the presence of Dust older than the solar system, the full set of nucleobases, and bio-essential sugars like Glucose and ribose in a single sample set forces a broader reframing of where and when life’s ingredients are assembled. Rather than being a rare outcome confined to a narrow set of conditions, complex organic chemistry now appears to be a natural byproduct of processes that operate in many small bodies. The OSIRIS mission, led by NASA and The OSIRIS-REx team, has shown that even a rubble pile asteroid can host a rich interplay of water, rock, and organics, and that fragments of possible ocean worlds can survive long enough to deliver their cargo to planets like Earth. For me, the real surprise in the Bennu samples is not just the exotic phosphate glass, but the way it ties together so many threads, from stellar Dust to ocean chemistry, into a single, tangible story about how a lifeless universe builds the tools that life will one day use.

Supporting sources: Scientists find traces of life’s building blocks in historic asteroid ….

More from MorningOverview