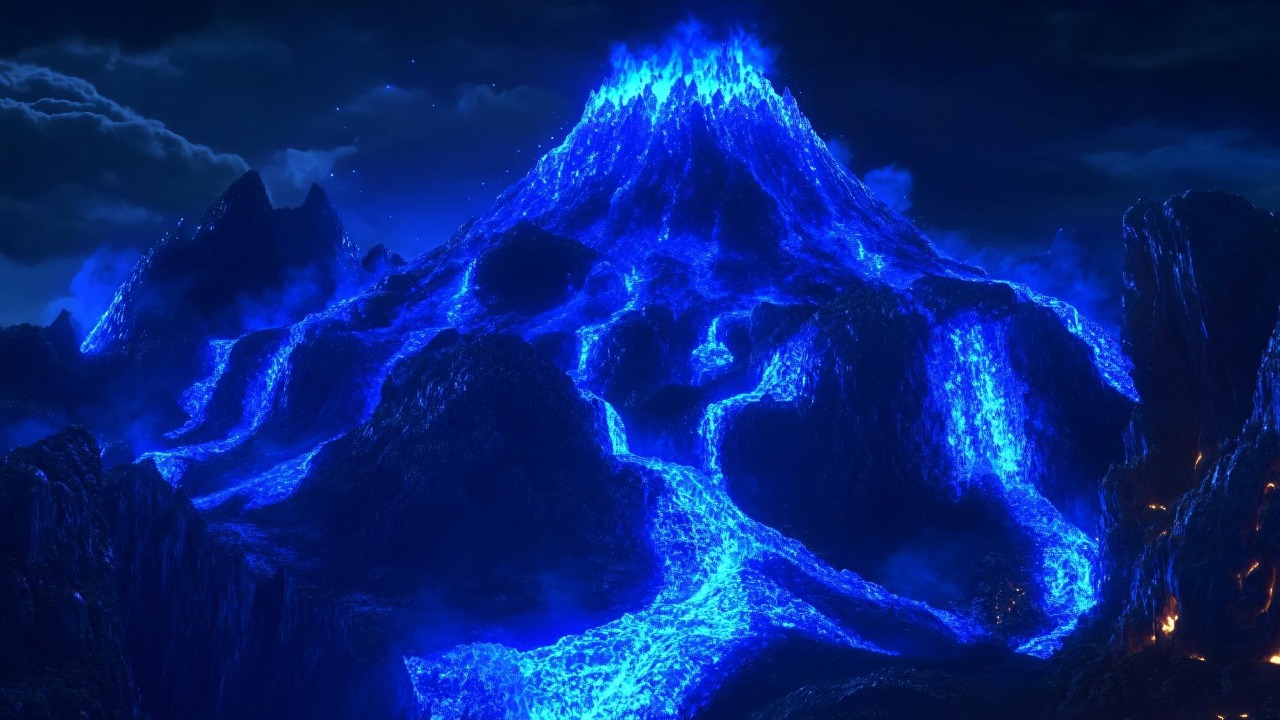

On the slopes of an Indonesian volcano, rivers of light appear to pour out of the dark, glowing an electric blue that looks more like a movie effect than geology. The spectacle is real, but the molten glow is not what most people think of as lava, and the physics and chemistry behind it are stranger than the photographs suggest. When I trace how this illusion works, from the gases in the crater to the cameras pointed at it, the story of “blue lava at night” turns out to be a collision of extreme chemistry, human labor and clever image making.

Where on Earth “blue lava” actually exists

The place that made blue lava famous is Kawah Ijen, an active crater on the east side of Java that sits inside a larger volcanic complex known as the Ijen volcano. The crater holds a turquoise acid lake and a dense field of sulfur vents, and it is here that visitors hike in the dark to watch what looks like neon magma sliding down the rock. Guides describe the route up Kawah Ijen as steep and dusty, but the payoff is a view into a pit that, at night, seems to be lit from within by electric fire.

Geologically, Kawah Ijen is part of a chain of peaks that includes the wider Ijen plateau, and the crater floor has become famous enough that some maps now highlight its location as a destination in its own right. The same volcanic complex appears again in other mapping tools that mark the Ijen volcano and its crater lake as a single, dramatic feature of eastern Java, reinforcing how tightly the idea of blue fire is tied to this one place. When I look at how often Kawah Ijen is singled out, it becomes clear that the “blue lava” label is really shorthand for a very specific corner of Earth.

Why the lava itself is not actually blue

The first misconception I have to strip away is the simplest: the molten rock in this crater is not a different color from lava anywhere else. The magma that feeds Kawah Ijen is typical of volcanic systems and, when it erupts, it glows in the familiar spectrum of bright red, orange and yellow that comes from incandescent rock at more than 1,000 degrees Celsius. Reports from the crater stress that what visitors see as a blue river is not a new kind of magma but a layer of something burning on top of ordinary, red-hot rock.

What makes the scene look alien is a sheath of ignited sulfur that coats the surface and edges of the lava and nearby rocks, creating what one account describes as red lava framed by a blue flame. Another analysis of the phenomenon is blunt that the glowing flow, often labeled “blue lava,” is not lava in the traditional sense at all, but a river of burning sulfur that happens to trace the same paths that molten rock would follow, which is why some descriptions put the word Lava in quotation marks. Once I separate the rock from the flame, the color puzzle starts to make sense.

The chemistry that turns fire into neon blue

The real driver of the spectacle is sulfur, which seeps out of vents in the crater as hot gas and liquid, then ignites when it meets the air. At Kawah Ijen, the concentration of sulfur is so high that it can pool and flow before it cools, and when this molten sulfur catches fire it produces flames that can reach several meters high. One detailed explanation notes that the flames can climb to about 5 meters, creating curtains of light that cling to the rock and, in places, run downhill like a glowing waterfall of liquid fire.

Chemically, sulfur burns with a characteristic blue color when it is hot enough, and the crater’s vents push temperatures past that threshold so the combustion emits light in the blue and violet part of the spectrum. A technical overview of Blue lava, also known in Indonesian as Api Biru, describes it as a sulfur fire that occurs when volcanic gases rich in sulfur emerge at high pressure and temperature and then ignite. Another breakdown of the “Blue Lava Volcano” effect points out that the blue color is not the rock itself but the flame from burning sulfur associated with some volcanoes, which is why the same chemistry can, in principle, appear anywhere the right mix of gas and heat exists.

Why the flames only look this dramatic at night

Even with all that sulfur burning, the crater does not glow like a nightclub around the clock. The blue color is relatively faint compared with the bright reds and oranges of incandescent rock, so in daylight the flames are largely washed out by the Sun and the glare of the surrounding landscape. Visitors who hike up Kawah Ijen in the middle of the day see yellow sulfur deposits and steam, not rivers of neon, which is why guides insist on starting the climb in the early hours of the morning.

Several accounts emphasize that the flames are difficult to see once the sky begins to brighten, and that the best viewing window is the deep night before sunrise when the crater is still in shadow and the human eye is more sensitive to blue light. One travelogue about Kawah Ijen describes hikers reaching the rim around midnight, then descending into the crater so they can watch the flames at their peak intensity before dawn washes them out. A separate explanation of the effect notes that the Ijen lava appears blue only in the dark and becomes much harder to see in daylight, a reminder that part of the magic is not just chemistry but timing, as one analysis of the Ijen lava makes clear.

The human story inside the blue glow

It is tempting to treat the blue fire as a pure spectacle, but the crater is also a workplace, and the same sulfur that feeds the flames is mined by hand. At Kawah Ijen, men descend into the toxic gas with little more than cloth masks, break solid sulfur from the ground and carry loads that can exceed 70 kilograms up the crater wall on their shoulders. The blue light that tourists photograph is, for these miners, a byproduct of the material they haul out to sell, often for modest pay that barely covers the risks they take.

Photographer Olivier Grunewald, who helped bring images of the crater to global attention, has described how there is so much sulfur that at times it flows down the rock face as it burns, making it seem as though the miners are working beside a river of liquid blue. Another feature on the phenomenon notes that the miners are trying to support their families by any means possible, even if that means breathing in sulfur dioxide and walking for hours in the dark. When I look at the photographs with that context in mind, the blue fire reads less like a fantasy landscape and more like a harsh industrial site lit by its own exhaust.

How cameras, long exposures and the internet shaped the myth

The way most of us encounter blue lava is not in person but through photographs that exaggerate the effect in ways the eye cannot match. Many of the most striking images are shot with long exposures that allow the camera sensor to collect more light from the flames, turning flickering tongues of fire into smooth, continuous rivers of blue. The result is a scene that looks even more otherworldly than reality, with the sulfur fire painted as a solid, glowing stream that seems to pour out of the crater like liquid neon.

One detailed photo essay on the crater explains that the flames’ distinctive blue color comes from the combustion of sulfuric gases, which emit light when they burn, and that long exposures help capture that light in a way that makes it visible across the frame. A separate gallery of images of blue lava on Earth credits Grunewald with some of the most widely shared photographs, and notes that the camera’s ability to integrate faint light over time is part of why the phenomenon looks so intense in pictures. Once those images began circulating, they fed a feedback loop in which more visitors came to Kawah Ijen seeking the same shots, and more photographers pushed their settings to make the flames pop even more.

From obscure crater to bucket-list “Blue fire crater”

Before the blue flames became a viral image, Kawah Ijen was known mainly to volcanologists and local communities, but that changed once major outlets highlighted the spectacle. As soon as widely read features showcased the electric-blue glow, visitor numbers climbed, and the crater acquired a new identity as a “blue fire” destination. The site is now often labeled as a blue fire crater in guides and databases, and tour operators in Java market overnight trips specifically around the chance to see the flames.

An overview of Ijen notes that, since National Geographic mentioned the electric-blue flame of Ijen, tourist numbers have increased, turning the crater into a magnet for travelers who want to witness the phenomenon firsthand. Another travel guide titled Presentation of Kawah Ijen explains that the Ijen volcano and Kawah Ijen are now framed as a must-see for those visiting Indonesia, with the blue fire marketed as the highlight of the night hike. When I compare these accounts, I see how a niche scientific curiosity became a branded experience, complete with sunrise photo stops and social media itineraries.

Other places where blue flames erupt

Kawah Ijen is the most famous example of blue lava, but it is not the only place where volcanic gases ignite in unusual colors. In Hawaii, for instance, observers at Kilauea have reported blue flames flickering along the ground during certain eruptions, though the chemistry there is different. Instead of sulfur, those flames are linked to methane that forms when lava buries vegetation and heats it until it releases flammable gas, which then seeps up through cracks and catches fire.

A report on blue flames at Kilauea explains that, while the Hawaiian volcano occasionally shows this effect, at the Kawah Ijen volcano in Indonesia the phenomenon is caused by sulfur, not methane. The same analysis notes that there, the blue flames are a more common sight because of the sheer volume of sulfur dust in the region’s soil and vents, which keeps feeding the fire. Another survey of Blue lava mentions that similar sulfur fires have been observed in places like Dallol Mountain in Ethiopia, although they are less accessible and less frequently photographed. These comparisons underline that the physics is universal, but Kawah Ijen is uniquely set up to showcase it.

The risks behind the beauty

For all its visual appeal, the blue fire is a symptom of an environment that is harsh and potentially deadly. The same sulfur dioxide that burns so beautifully can scar lungs and eyes, and the crater’s air can shift from breathable to choking in a matter of seconds when the wind changes. Tourists who descend into the crater at night often wear gas masks, but miners sometimes work with only a damp cloth over their mouths, and both groups navigate steep, rocky paths lit only by headlamps.

One detailed feature on the blue flames describes how the burning sulfur can form liquid flows that move quickly enough to surprise anyone standing too close, and how the ground near the vents is coated in brittle sulfur crusts that can crack underfoot. Another account of the Stunning Electric blue flames erupting from volcanoes notes that the flames can reach about 5 meters high, which means anyone approaching them is effectively standing next to a wall of fire. When I weigh the allure of the photographs against these details, it is clear that the “craziness” of blue lava is not just the color but the fact that people choose to walk into such a volatile space at all.

Why the science is stranger than the photos

What makes blue lava so compelling to me is that it flips the usual script of volcanic awe. Instead of a rare, exotic mineral or a new kind of magma, the key ingredients are familiar: sulfur, oxygen, heat and darkness. The strangeness comes from how those ingredients are arranged, with volcanic gas emerging at just the right temperature and pressure to ignite, then flowing over rock in a way that mimics molten stone. The result is a natural optical illusion that tricks the brain into seeing a new substance where there is only fire.

Scientific summaries of Despite appearances stress that the flames’ distinctive blue color is simply the visible light emitted when sulfuric gases combust, and that the phenomenon is a reminder of how much of Earth’s behavior is governed by basic physics. A broader overview of Indonesian blue lava notes that the same effect can, in principle, occur anywhere similar gases and temperatures coincide, even if only Kawah Ijen currently offers such a consistent show. When I step back from the viral images and look at the underlying processes, the explanation really is “even crazier” than the headline suggests, because it reveals a world where a small tweak in chemistry and timing can turn an ordinary volcano into something that looks like science fiction.

More from MorningOverview