When the polar vortex stumbles, the weather at ground level can pivot from mild to brutal in a matter of days. A circulation that usually spins quietly above the pole can suddenly send lobes of Arctic air plunging into the United States, Europe, or Asia, flipping local conditions from slushy rain to pipe-bursting cold. I want to unpack why that upper‑air breakdown happens, how it translates into fast, jarring swings where you live, and what forecasters are watching as the atmosphere lines up for another dramatic turn.

Scientists have been tracking signs that the vortex is “hitting the brakes,” with winds high over the Arctic slowing and temperatures in the stratosphere rising, a classic setup for a pattern change. When that circulation weakens or splits, the jet stream below often buckles, steering cold pools into places that had been enjoying relative warmth just days earlier. Understanding that chain reaction is the key to making sense of why your local forecast can go from light jackets to dangerous wind chills almost overnight.

What the polar vortex actually is

I start with the basic structure: the polar vortex is not a single storm, but a broad region of low pressure and strong winds that circles the pole high in the atmosphere. In the Arctic and Antarctic, this circulation forms each winter as darkness and intense cooling set in, tightening into a cold “whirlpool” of air. In the Northern Hemisphere, that ring of westerly winds tends to be strongest in midwinter and weakest as spring approaches, which is when it becomes more vulnerable to disruption.

Most of the time, this upper‑level system helps keep the coldest air bottled up near the pole, especially in the Northern Hemisphere where population centers sit much farther south. When the vortex is strong, the flow of Arctic air is organized and tends to stay locked in place, but when it is very weak the circulation becomes disorganized and lobes of frigid air can spill south. That structural shift is what turns an abstract feature of the upper atmosphere into a very real blast of winter at ground level.

How a “break” in the vortex flips surface weather

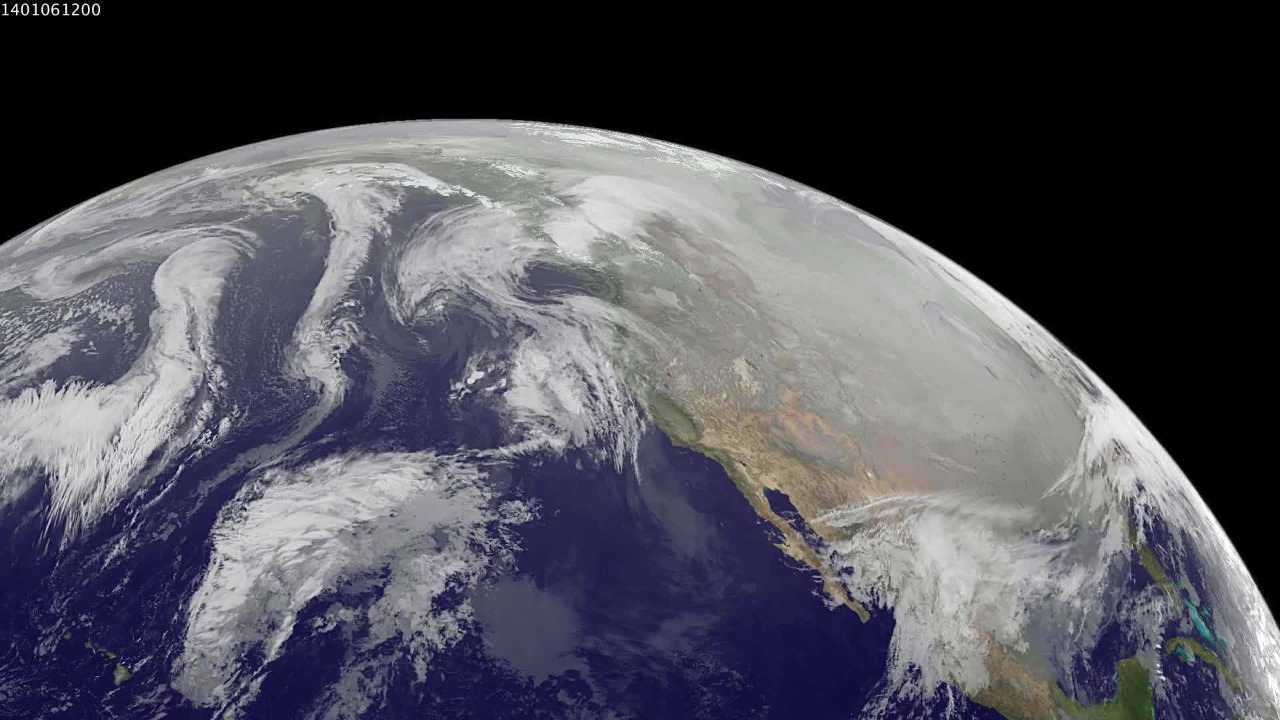

The fast flips people feel on the ground usually start with a slowdown or distortion of the vortex winds tens of kilometers above the surface. Earlier this year, scientists tracking the circulation at 60 degrees north latitude noted that those high‑altitude winds were “hitting the brakes,” a sign that the once tight ring of air was weakening. As that happens, waves in the atmosphere can shove the vortex off center or even split it, creating separate cold cores that migrate toward mid‑latitudes.

Once those lobes start to move, the jet stream below tends to kink and meander, opening the door for Arctic air to surge south into North America, Europe, or Asia. For this upcoming event, forecasters expect temperatures in the stratosphere to spike as the vortex deforms, with the main lobes of cold air dropping into lower latitudes several days later. That lag is why your local forecast can look benign at the start of the week, then suddenly advertise a brutal cold snap as the displaced vortex finally connects with the surface pattern.

Sudden stratospheric warming: the trigger behind dramatic shifts

One of the most dramatic ways the vortex can break is through sudden stratospheric warming, often shortened to SSW. In these events, waves from the lower atmosphere surge upward and dump energy into the stratosphere, causing temperatures there to jump by tens of degrees in a matter of days. Meteorological data now hints that the atmosphere is lining up for another such SSW, which would dramatically weaken the vortex and set the stage for a reshuffling of weather patterns across the Northern Hemisphere.

Forecasters pay close attention to these signals because they often precede extended cold spells or blocking patterns at the surface. The “Why It Matters” is straightforward: when the stratosphere warms and the vortex collapses, the odds of severe or persistent chilly conditions increase in the weeks that follow. Forecasters use these high‑altitude clues to flag the risk of a pattern flip long before surface models fully catch up, which is why you might hear about a “major, sudden” phenomenon before you feel any change outside your window.

From Arctic sky to your street: the mechanics of a cold plunge

To understand how a wobble in the vortex becomes a biting wind on your street, I look at the vertical chain of events. The Arctic polar vortex sits in the stratosphere during winter, and Understanding the Arctic circulation means recognizing that it is coupled to the jet stream below. The Arctic vortex strengthens as polar night deepens, then weakens as sunlight returns, and When the vortex is disturbed, the jet stream tends to become wavier and more prone to locking weather patterns in place.

Closer to the surface, the polar jet stream acts as the steering current for storm systems and air masses. When the vortex weakens, that jet can dip far south, allowing Arctic air to spill into mid‑latitudes and linger. In practical terms, that is how a region like the central United States can go from relatively mild conditions to record‑breaking cold in a few days, as a lobe of frigid air that once circled harmlessly over the pole is redirected into heavily populated areas.

Why a weaker vortex means stronger cold where you live

It might sound counterintuitive, but a strong vortex high above the pole usually means less extreme cold for most of the United States and Europe. When the circulation is tight, the spinning winds act like a barrier that keeps the coldest air locked in place. The question, How Can the Polar Vortex Cause Extremely Cold Temperatures in the US, is answered by what happens when that barrier fails. Sometimes the vortex weakens so much that the jet stream can no longer maintain its usual path, and the cold air that was once confined near the pole pours south.

That breakdown is what turns a distant atmospheric feature into a local hazard. As the jet stream buckles, one region can be plunged into a deep freeze while another basks in unusual warmth under a ridge of high pressure. The same process that delivers subzero wind chills to the Midwest can leave Alaska or parts of the Arctic milder than normal, a reminder that the vortex is redistributing cold rather than creating it from scratch.

The jet stream’s role: when “wavier” means wilder

Once the vortex starts to wobble, the polar jet stream often becomes more sinuous, carving deep troughs and sharp ridges across the hemisphere. Normally, the polar jet forms a relatively smooth band of fast winds that circles the globe, helping to keep cold and warm air masses separated. As experts on Arctic change have noted, Normally, the polar vortex has a more compact shape, but when the jet becomes wavier, it can drag tongues of Arctic air far south and pull warm subtropical air far north.

Those exaggerated waves are what turn a routine cold front into a headline‑grabbing event. A deep trough can stall over one region, locking in a prolonged cold spell, while a neighboring ridge keeps another region unseasonably warm and dry. That contrast can make a cold spell much worse, because the atmosphere is essentially amplifying the difference between air masses, sharpening temperature gradients and fueling stronger storms along the boundaries.

Real‑world impacts: from record Midwest cold to a Florida chill

The abstract mechanics of a vortex breakdown become very concrete when you look at recent cold outbreaks. Millions of people across the Midwest and Northeast woke up to extreme cold that was breaking records as it spread east, a direct result of a lobe of the vortex sliding south. In that event, The polar vortex is a circular current of strong winds high in the atmosphere over the Arctic that usually keeps brutally cold air corralled, but when it weakened, that air spilled into heavily populated areas. The result was school closures, infrastructure strain, and dangerous conditions for anyone caught outside without proper protection.

The reach of a disrupted vortex is not limited to traditionally cold regions. As a strong front pushed south, Temperatures were forecast to drop significantly across Florida, with some areas flirting with freezing conditions and West Palm Beach dropping to 50 degrees. For residents used to balmy New Year’s celebrations, that kind of chill feels abrupt, but it is part of the same hemispheric rearrangement that sends Arctic air surging south when the vortex loses its grip.

How long the cold lasts when the vortex “strikes back”

Once a lobe of the vortex has been displaced, the next question is how long the cold will stick around. An overview of Earth’s Polar Vortex shows that high above the High latitudes near the North Pole, the vortex can exert an extended influence on winter temperature patterns. Generally, when the polar vortex is strong and centered, cold outbreaks are shorter and more transient, but when it is weak or split, the resulting pattern can lock in for weeks.

At the surface, the duration of a cold spell depends on how the jet stream sets up after the initial displacement. Most of the time, this kind of outbreak lasts a few days before the pattern shifts, but in some years the cold can persist much longer. How long a particular vortex outbreak persists varies greatly, which is why some winters feature a quick cold snap and others deliver a grinding, weeks‑long freeze that tests power grids and public services.

Forecasting the next flip: what models are seeing now

Looking ahead, long‑range meteorologists are watching the polar vortex closely for signs of another breakdown. As the season has progressed, a Polar vortex shift has been poised to unleash more bitter cold across the US through mid‑December, with More Arctic air building and ready to surge south. That kind of guidance tells me that the atmosphere is primed for another fast flip, even if the exact timing and track of the cold air remain uncertain.

At the same time, specialists tracking the stratosphere have highlighted that the vortex winds at 60 degrees north are slowing, a classic precursor to a more substantial disruption. In Mar, that kind of signal often marks the transition toward spring, but when it appears earlier in the season it can foreshadow a major pattern change. I read those signs as a warning that the atmosphere is entering a more volatile phase, where the odds of rapid temperature swings and high‑impact storms are elevated.

What “polar vortex” headlines get wrong

Every time the term pops up in headlines, it tends to be used as shorthand for any winter storm or cold snap, which muddies the science. In reality, the phrase refers to the high‑altitude circulation, not the snow in your driveway. The “polar vortex” is a large‑scale feature that can contribute to cold temperatures and heavy snow when it weakens, but not every winter storm is a direct result of its behavior. Jan headlines that treat it as a single monster storm miss the nuance of how it interacts with the jet stream and surface weather systems.

There is also a tendency to treat the vortex as a new phenomenon, when in fact it has been a fixture of the winter atmosphere for as long as we have had seasons. Dec explainers have emphasized that What people are really feeling is the effect of Cold, Arctic air that is severe but usually kept tightly contained. Fortunately, strong polar winds create a kind of atmospheric fence most of the time, which is why the most extreme cold outbreaks remain relatively rare even in a warming climate.

More from MorningOverview