Humanity has been leaking radio noise into the cosmos for just over a century, and those signals now form a vast, expanding shell around our planet. That invisible sphere, often called Earth’s radio “bubble,” marks the true edge of our technological footprint in the galaxy, far beyond the reach of any spacecraft. Thinking about how large that bubble has grown, and what it contains, is a way to measure not only our engineering progress but also how loudly we are announcing our presence to anyone who might be listening.

From early broadcasts to deliberate messages aimed at other stars, each transmission adds another faint layer to this shell of electromagnetic evidence. I see that bubble as both a scientific marker and a cultural mirror, revealing what kind of civilization we have become in the short time since we learned to speak with radio waves.

How big Earth’s radio bubble really is

When scientists talk about a radio “bubble,” they are describing the distance our strongest signals have had time to travel at the speed of light since the dawn of radio. The most widely used estimate puts the radius of this shell at 119 light-years, which means the full sphere is 238 light-years across. In other words, any hypothetical observer within that radius could, in principle, have already been bathed in at least some of our emissions, from early Morse code and analog radio to modern radar and television.

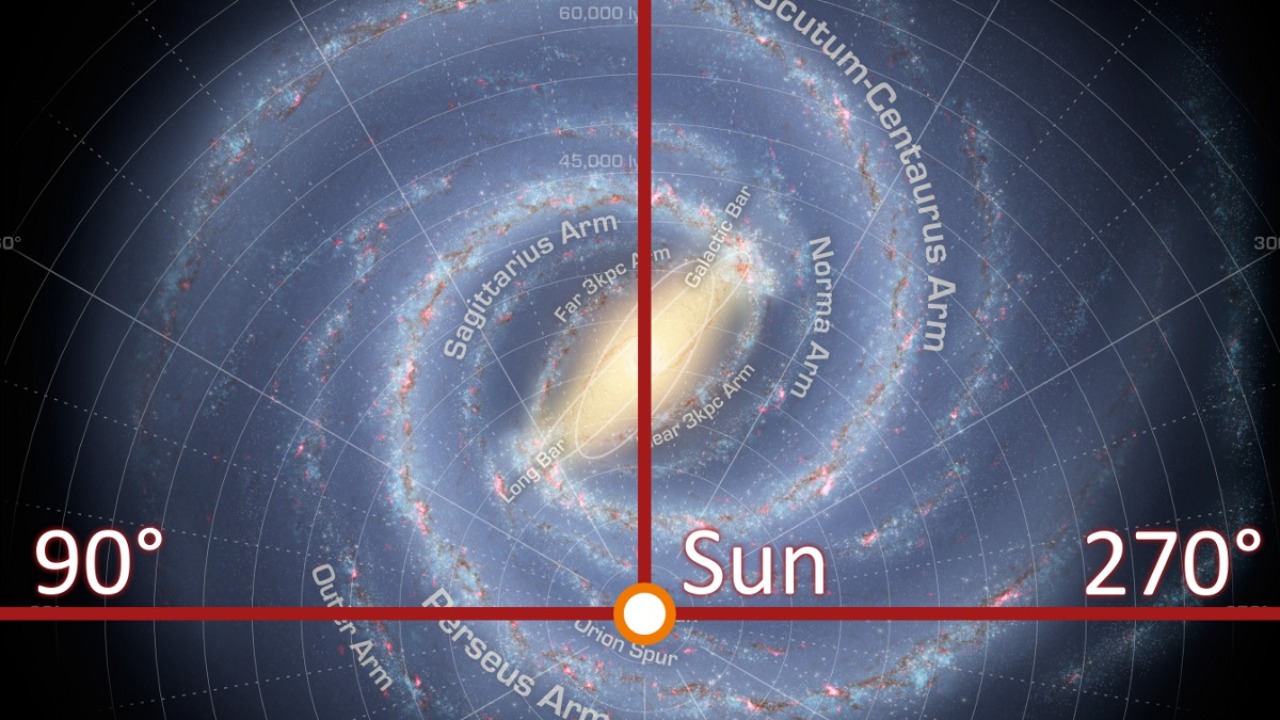

Visualizations of this shell show just how tiny it still is compared with the Milky Way, which spans roughly 100,000 light-years. In one widely shared graphic, the illuminated region around the Sun is a small, bright dot embedded in a vast dark disk of stars, a reminder that our technological reach is still confined to a minuscule neighborhood despite the impressive size of the extent of human radio broadcasts. I find that contrast useful: it tempers the popular image of a galaxy already saturated with our chatter and replaces it with a more modest picture of a young civilization just beginning to speak up.

From Fessenden’s voice to a century of leakage

The story of this expanding shell begins with some of the earliest experiments in wireless communication. Among the landmark moments was the work of Reginald Fessenden, whose pioneering broadcasts helped move radio from dots and dashes to full audio. Those first transmissions were not designed with the cosmos in mind, yet they became the leading edge of the bubble, racing outward at light speed and defining the maximum distance at which any alien astronomer could, in theory, have heard human voices.

In the decades that followed, the volume and variety of our radio leakage exploded. Commercial AM and FM stations, military and civilian radar, satellite uplinks, and television carriers all contributed to a noisy electromagnetic environment around Earth. Over time, that noise has filled the interior of the bubble so thoroughly that any distant listener inside it would encounter a complex blend of overlapping signals rather than a single clear beacon, a pattern that reflects how quickly our species embraced radio as the nervous system of a global society.

What a “bubble” of radio actually looks like

It is tempting to imagine the radio shell as a sharp boundary, like the surface of a balloon, but the physics is more subtle. When I picture it, I think of a gradient: the earliest transmissions form the outermost, faintest layer, while newer signals occupy inner shells that are still relatively strong. As one analysis explains, When we send out a strong, uninterrupted radio transmission, it spreads in all directions, thinning as it goes, so the bubble is really a nested set of fading waves rather than a solid wall.

That structure matters for detectability. Near Earth, the signal density is high, with countless overlapping broadcasts and radar pulses, but by the time those waves reach the outer edge of the 119 light-year radius, each individual transmission has been stretched into a whisper. The result is a sphere that is roughly 238 light-years across but far from uniform, with bright patches where powerful radars or long-running broadcasts dominate and dimmer regions where only the faint echo of older signals survives.

Which stars are already inside our radio sphere

Even a modest bubble can encompass a surprising number of neighboring stars. The expanding shell has already swept past some of the closest systems to our own Sun, including well known neighbors such as Proxima Centauri. That means any hypothetical observers orbiting those stars, if they had sensitive enough instruments and happened to be listening at the right frequencies, could already have noticed the telltale pattern of artificial radio noise coming from our direction.

Statistical studies of exoplanets suggest that a significant fraction of stars within this radius are likely to host rocky worlds. One estimate notes that at least 25 per cent of a sample of 75 nearby star systems that can both see Earth transit the Sun and lie within our radio reach probably have terrestrial planets, a conclusion drawn from Exoplanet statistics. I read that as a reminder that our bubble is not just expanding into empty space, it is already overlapping with potentially habitable real estate where someone else’s telescopes might be pointed our way.

How faint are we, really, from light-years away?

Size is only half the story, because a bubble 119 light-years in radius is impressive on paper but useless for contact if the signals are too weak to notice. As radio waves spread out, their intensity drops with the square of the distance, so a broadcast that is deafening on Earth becomes almost unimaginably faint after crossing dozens of light-years. That is why many astronomers argue that casual leakage, such as television and FM radio, would be extremely hard to pick out against the background noise of the galaxy, even for a very advanced civilization.

To test what might be detectable, researchers have modeled how far our most powerful transmissions could be heard with equipment comparable to our own. One study concluded that with Modern Technology, planetary radar signals could be picked up from Up To 12,000 Light-years away, while weaker, intermittent emissions would fade into the background much closer in. That result is echoed by work that treated Earth itself as a target, showing that radar bursts from facilities like the Arecibo Observatory could stand out across thousands of light-years, whereas ordinary broadcasts would be invisible beyond a relatively small neighborhood.

Deliberate messages versus accidental noise

Not all of our radio footprint is accidental. On a few occasions, scientists have intentionally aimed messages at specific targets, turning Earth into a kind of interstellar lighthouse. One of the most famous examples came when Astronomers used the Arecibo Observatory in Puerto Rico to beam a carefully encoded signal toward a star cluster, a transmission that has been traveling outward for decades and will eventually leave the solar system entirely. That message was brief but extraordinarily powerful, designed to be unmistakable against the cosmic background if anyone happens to be listening along its path.

These deliberate beacons sit on top of the much larger sea of unintentional emissions, and they raise different questions about how we want to present ourselves. I see a clear distinction between the messy, unfiltered portrait offered by our everyday radio noise and the curated, symbolic self-portrait encoded in a targeted message. The former tells any eavesdropper what we are actually like, with all our flaws and contradictions, while the latter is closer to a calling card, a conscious attempt to shape how a stranger might first come to know us.

Could anyone out there already have answered?

If our signals have reached other stars, it is natural to ask whether any of them might already have replied. The timing is tricky, because even a relatively nearby system would require decades for a round trip at light speed. Some researchers have tried to identify specific stars that have already been illuminated by our transmissions and could, in principle, send something back that would arrive within our lifetimes, focusing on those that lie within both our radio sphere and the narrow cone from which Earth can be seen crossing the Sun.

One analysis of potential response windows points out that any return signal would depend on many factors, including how long or often we monitor a given star and whether our instruments are in the right place to capture the evidence. That uncertainty is compounded by the fact that our own listening campaigns are intermittent and limited in frequency coverage, so even if a distant civilization had already noticed our bubble and decided to respond, there is no guarantee we would be looking at the right time or in the right way to notice their reply.

How many potentially habitable worlds lie inside the bubble

Beyond individual stars, astronomers have tried to estimate how many Earth-like planets might already be inside the region touched by our radio noise. One recent assessment argued that the earliest broadcasts have had time to wash over at least Theoretically at least 29 potentially habitable exoplanets, based on known planetary systems and statistical models of where rocky worlds are likely to form. That figure is modest compared with the hundreds of billions of planets in the Milky Way, but it is striking when you remember that our radio age spans barely more than a century.

I read that number as a lower bound rather than a ceiling, because it only counts worlds we have already identified or can reasonably infer. As surveys improve and more small planets are discovered around nearby stars, the tally of potentially habitable worlds inside our radio sphere is likely to grow. Each new detection adds another possible audience for the signals that have been streaming outward since the early days of wireless, turning the abstract idea of a bubble into a more concrete map of specific places where our presence is already, in principle, on the record.

What our expanding radio shell says about us

Thinking about Earth’s radio bubble is ultimately a way of thinking about ourselves. The shell’s 119 light-year radius and 238 light-year diameter are not just geometric facts, they are a timestamp on the age of our technology and a measure of how quickly we have transformed our planet into a source of artificial radiation. Inside that sphere, any sufficiently advanced observer could reconstruct a rough history of our development, from the first crackling broadcasts to the rise of powerful radars and digital communication systems.

At the same time, the bubble highlights how young and local our technological story still is. Even if our strongest signals can, in principle, be detected from Up To 12,000 Light-years away under ideal conditions, the region that has actually been illuminated by more than a century of continuous leakage remains a tiny patch of the Milky Way. I find that humbling. It suggests that, for now, we are a small, noisy civilization announcing itself to a handful of nearby stars, with the vast majority of the galaxy still unaware that a species on a pale blue dot has learned to speak in radio at all.

More from MorningOverview