For more than a century, fossils meant bones, shells and the occasional imprint of a leaf. Now, a wave of research is showing that the most revealing relics of ancient organisms are not their shapes at all but the fragile molecules they left behind. By decoding those chemical traces, scientists are starting to reconstruct what early life actually looked like, how it made a living and how it transformed a young planet.

Instead of treating rocks as static relics, researchers are learning to read them as molecular archives, packed with “whispers” of vanished cells and metabolisms. I see that shift as one of the most radical changes in how we picture deep time, because it turns seemingly blank stone into a record of color, chemistry and even behavior that traditional fossils could never capture.

From bones to “molecular fossils”

When most people imagine paleontology, they picture towering dinosaur skeletons or trilobites pressed into shale. Yet the bulk of Earth’s history, and the majority of its inhabitants, never produced hard parts that could fossilize in that familiar way. To understand those worlds, scientists have turned to what they call molecular fossils, the durable fragments of cell membranes, pigments and metabolic byproducts that can persist long after the original tissues have vanished.

Researchers now treat these molecular remnants as a parallel fossil record that fills in the gaps left by bones and shells. Work led by David Gold, an associate professor in the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences at the University of California, Davi, has helped formalize how these chemical signatures can be traced through rocks to reconstruct ancient ecosystems, treating them as rigorously as any skeleton on a museum floor.

The 3.3 billion year leap into Earth’s earliest biosphere

The most dramatic payoff from this molecular approach has arrived in some of the oldest rocks on the planet. A team working with samples more than 3.3 billion years old has uncovered chemical evidence that life was already thriving in environments that long predate any visible fossil. Those rocks, once thought to be geologically interesting but biologically mute, now read like a faint but legible diary of early microbes.

In that work, scientists identified subtle patterns in carbon-bearing compounds that point to biological processing rather than simple chemistry. One report describes how Indeed, this new research shows that life left behind more than anyone realized, with those faint chemical “whispers” locked inside minerals that can be viewed only through a microscope. For me, the striking part is not just the age of the rocks but the realization that what once looked like sterile stone is now recognized as a crowded, if invisible, biosphere.

How AI pulled hidden life out of ancient rocks

Finding such subtle signals in ancient rock is not as simple as pointing a microscope and hoping for the best. The original biomolecules have long since broken down, leaving only fragmented echoes that are easily confused with non-biological chemistry. To separate life’s residue from background noise, researchers have turned to machine learning, training algorithms to recognize the complex patterns that metabolism imprints on matter.

In one project described as a Discovery of Ancient Chemical Traces of Life, scientists fed spectrometric data from 3.3 billion year old rocks into an AI system that could distinguish biological from abiotic signatures even after the original biomolecules had broken down. Another account notes that the work was carried out By Michigan State University November, with MSU researcher Katie Maloney contributing samples that allowed the models to learn what biological “fingerprints” look like in deep time. I see this as a turning point, where artificial intelligence becomes a kind of translator between ancient chemistry and modern biology.

Why these traces push the biochemical record back in time

For decades, the biochemical record of life seemed to hit a hard wall in the mid-Proterozoic. As one analysis puts it, But direct evidence, the biochemical record, only dates back about 1.6 billion years. That left a yawning gap of nearly two billion years between the planet’s formation and the first solid molecular proof of life, a period that was often treated as speculative territory.

The new work on Earliest Chemical Traces of Life in 3.3-Billion-Year Old Rock effectively doubles the age of that biochemical record. A related report describes how Earliest Chemical Traces of Life on Earth Discovered in 3.3-Billion-Year Billion Year Old Rock are now considered the oldest such signals found on Earth to date. That shift does not just move a date on a timeline, it forces me to imagine a much more biologically active early Earth than many models assumed.

What the earliest molecules say about how ancient life lived

Knowing that life existed 3.3 billion years ago is one thing, but molecular fossils can go further by hinting at what those organisms were actually doing. The chemical patterns in the rocks suggest metabolisms that processed carbon, sulfur and possibly methane, consistent with tiny microbes eking out a living in environments that would look alien to us today. These were not large, complex creatures but microscopic pioneers that still managed to reshape their surroundings.

One summary notes that Life on early Earth left behind only sparse molecular evidence because Fragile materials such as primitive cells and microbial mats decayed quickly. Yet the surviving compounds, preserved in 3.3 billion year old rocks and even some meteorites, still carry enough information to infer that these early communities were metabolically diverse. I read that as a reminder that even the simplest cells can leave a complex chemical footprint when given geological time.

Cracking open rocks to hear life’s “echoes”

To access those faint signals, scientists have had to invent new ways of interrogating ancient minerals without destroying what little information they contain. One team used sophisticated spectrometry to heat and crack open microscopic inclusions inside the rocks, releasing trapped chemical fragments that had been sealed away for billions of years. The process is akin to opening a time capsule, except the contents are measured as peaks on a graph rather than seen with the naked eye.

A detailed description explains how They used sophisticated spectrometry to release trapped chemical fragments from each sample, then applied a specialized machine learning model to identify biological “echoes” for the first time. The combination of high precision instruments and pattern recognition algorithms turns each grain of rock into a dataset, one that can be mined for clues about ancient metabolisms. For me, that technical leap is what transforms abstract talk of “chemical whispers” into something concrete and testable.

Million-year-old metabolisms and what they reveal about ancient worlds

Molecular fossils are not limited to the very oldest rocks. In younger, better preserved specimens, scientists can sometimes recover intact pieces of the machinery that once powered living cells. A recent study reports that Scientists Extract Metabolic Molecules From Million Year Old Fossils for the First Time, pulling out compounds that once shuttled energy through ancient organisms.

Those metabolic molecules do more than prove that chemistry can survive for a million years. The same study notes that the fossils came from environments that were significantly wetter than they are today, implying that the organisms lived in ecosystems with very different climate regimes. The report, attributed By New York University Decemb, uses those molecules to reconstruct not just the biology of the fossils but the humidity, temperature and water availability of their long vanished habitats. I find that especially powerful, because it shows how a single chemical pathway can double as both a biological and environmental archive.

Color, texture and the look of ancient animals

If early microbial life is hard to picture, larger animals from the more recent past are easier to imagine, yet even there molecular fossils are changing the visual story. Traditional skeletons can tell us how big a creature was or how it moved, but they say little about its colors, soft tissues or internal chemistry. By extracting preserved molecules from animal fossils, researchers are starting to fill in those missing details.

One account describes how Fossils have provided scientists with incredible insights into the prehistoric world, but notes that hidden molecules in an animal fossil are now revealing how the ancient world looked in ways that go beyond bones. Those molecules hint at pigmentation, diet and even aspects of physiology, painting a picture of ecosystems that were more colorful and chemically complex than our world is today. When I think about that, I realize that every new molecular technique effectively upgrades our mental “graphics” of prehistory.

Seeing early Earth through microscopic patterns

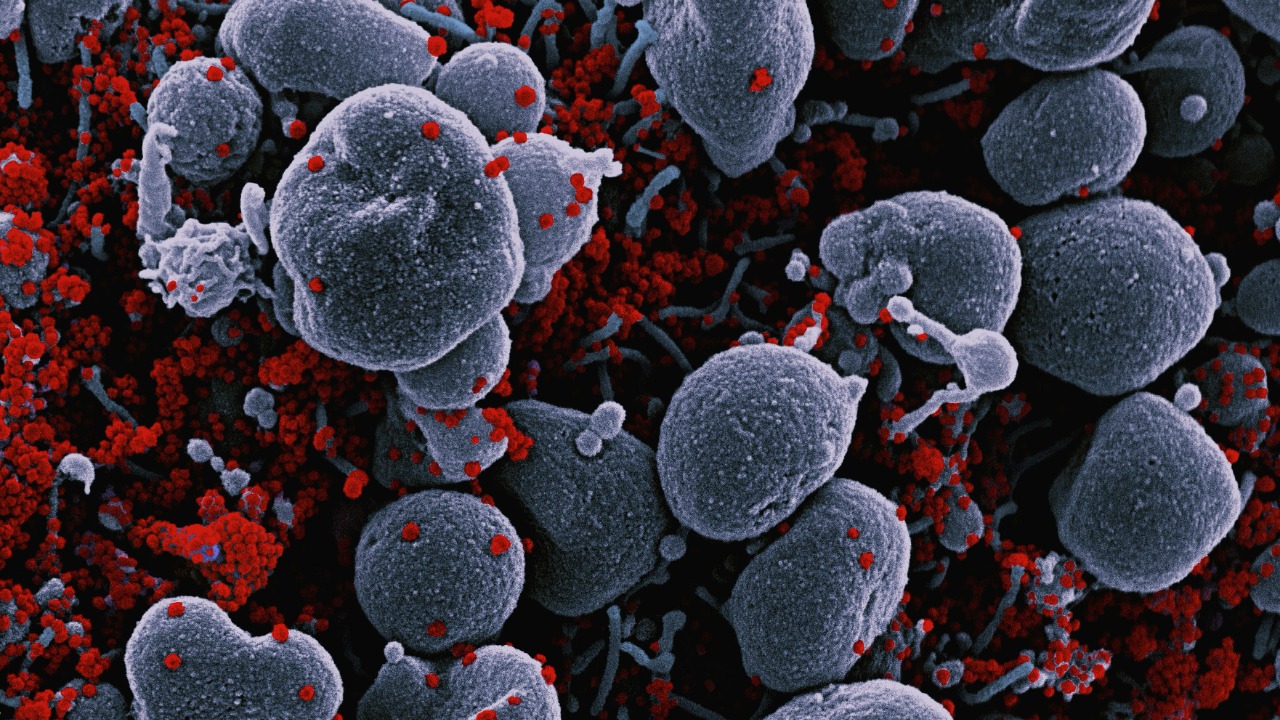

Some of the most evocative glimpses of ancient life come not from massive excavations but from tiny patterns etched into rock surfaces. In one widely shared video, a researcher points to subtle textures in a 3.3 billion year old sample and explains that these patterns, though to the human eye just random swirls, actually reveal signs of life from over 3 billion years ago. The organisms responsible were Likely tiny microbes that left behind chemical and structural traces rather than recognizable body fossils.

The same clip emphasizes that these microscopic features are part of the earliest traces of life on Earth, too, tying visual textures to the molecular signals identified in the lab. For me, that convergence of imagery and chemistry is what finally makes the deep past feel tangible. It is one thing to read about isotopic ratios and spectrometric peaks, another to see the actual rock surfaces where those ancient communities once clung and to know that their molecular fingerprints are still embedded there.

Why fragile molecules may outlast visible fossils

At first glance, it seems counterintuitive that delicate organic molecules could survive longer than robust shells or bones. Yet in many settings, the opposite is true. Hard tissues can be ground down, dissolved or metamorphosed beyond recognition, while tiny organic fragments slip into mineral pores or become bound to crystal lattices that shield them from further decay. Over billions of years, that protective encapsulation can make molecular ghosts more durable than the bodies that produced them.

Researchers studying early rocks emphasize that Life on early Earth left behind only sparse molecular evidence precisely because so much of its material was Fragile. Yet the few molecules that did find safe harbor in 3.3 billion year old rocks and meteorites are now more informative than any hypothetical microfossil would have been. I see that as a humbling reminder that what survives in the geological record is not always what we expect, and that the smallest traces can carry the biggest stories.

The next frontier: mapping a chemical atlas of deep time

Put together, these studies suggest that we are only at the beginning of what molecular fossils can tell us. The combination of high resolution spectrometry, AI pattern recognition and careful fieldwork is turning isolated discoveries into the first outlines of a global chemical atlas, one that tracks how life’s molecules changed as continents shifted, atmospheres evolved and climates swung between extremes. Each new dataset adds another layer to that map, revealing not just when life existed but how it adapted.

One overview of the 3.3 billion year old work notes that Indeed, this new research shows that life left behind more than anyone ever realized, suggesting that similar “whispers” may be waiting in other ancient formations around the world. As techniques improve, I expect that what we now call the earliest chemical traces will be pushed back further, and that the picture of ancient life will sharpen from a few scattered points into a continuous, molecule-by-molecule portrait of Earth’s living past.

More from MorningOverview