Physicists are starting to argue that the same machines built to recreate the power of the Sun on Earth could also double as laboratories for the invisible matter that dominates the cosmos. Instead of sending ever larger detectors into deep mines or space, they suggest that fusion reactors themselves might manufacture the very dark matter particles that have eluded astronomers for decades. If that idea holds up, the race to commercial fusion could unexpectedly merge with the hunt for the universe’s missing mass.

At the heart of this proposal is a simple but radical shift in perspective: treat the extreme conditions inside a fusion device not just as an energy source, but as a controlled version of the early universe. In that view, the same reactions that promise nearly limitless clean power might also produce exotic particles that behave nothing like ordinary atoms, opening a new front in one of physics’ most stubborn mysteries.

Why dark matter needs a new kind of laboratory

Dark matter earned its name because it does not shine, absorb, or reflect light, yet its gravity shapes galaxies and galaxy clusters. Astronomers infer its presence from how stars orbit in spirals and how massive structures bend background light, but decades of underground experiments and particle collider runs have failed to catch a single dark matter particle in the act. That stalemate has pushed theorists to look for environments that mimic the high energies and dense plasmas of the early cosmos, where such particles might have been created in abundance.

In that context, the idea that a fusion device could act as a miniature Big Bang is more than a metaphor. Theorists working on dark sector models argue that the same nuclear reactions that power a reactor core could, in principle, radiate new particles that barely interact with normal matter, a category that includes candidates like axions and other light, weakly coupled fields. One recent analysis of fusion and dark matter notes that dark matter is called dark because, unlike normal matter, it does not absorb or reflect light, yet physicists still hope to detect it indirectly by watching how it might siphon energy or momentum from a hot plasma, a strategy that underpins new work on how fusion reactors may be key to uncovering dark matter, as described in recent theoretical studies.

From Big Bang jokes to serious axion physics

Axions sit at the center of many of these proposals, and they have an unlikely pop culture footprint. In one episode of a long running sitcom about physicists, a whiteboard in the background shows an equation and diagram that a real theorist later recognized as a sketch of how axions could be generated from a hot plasma. That Easter egg was not just a throwaway gag, it reflected how deeply axions have seeped into the imagination of particle theorists who see them as a natural way to solve puzzles in the strong nuclear force while also providing a viable dark matter candidate.

The same researcher, identified as Zupan in university reporting, has since used that television moment as a springboard to explain how axion production might actually work in realistic physical systems, including fusion environments. In coverage of his work, Zupan points out that the fictional whiteboard captured a real mechanism for axion generation, and that there are many layers to the jokes when a show leans on genuine high energy physics, a connection highlighted in a profile that notes how Zupan used the scene to discuss axions with a broader audience.

The new fusion–dark matter theory on the table

Behind the headlines about fusion reactors spawning dark matter is a concrete theoretical paper that treats the reactor as a particle factory. In that work, the authors model how a hot, dense plasma of deuterium and tritium could emit exotic scalar particles or axion like fields during fusion reactions, then track how those particles would escape or interact with the surrounding material. The key claim is that the same conditions engineers already aim for in commercial reactors, such as high temperature and sustained burn, are precisely the ones that maximize the production of these hypothetical particles.

The technical backbone of this argument appears in a peer reviewed article with the DOI written explicitly as 10.1007/JHEP10(2025)215, published in the Journal of High Energy Physics. That paper, titled “Searching for exotic scalar particles in fusion plasmas,” lays out how a reactor scale plasma could emit new light fields and how detectors might pick up their subtle signatures, turning a power plant into a precision experiment. The formal citation details, including the Journal, the Journal of High Energy Physics label, the DOI string beginning with 10.1007 and the article number 215, are presented in a summary of the work that underscores how “Searching for” such particles has moved from speculation into a structured research program.

How a fusion reactor becomes a dark matter machine

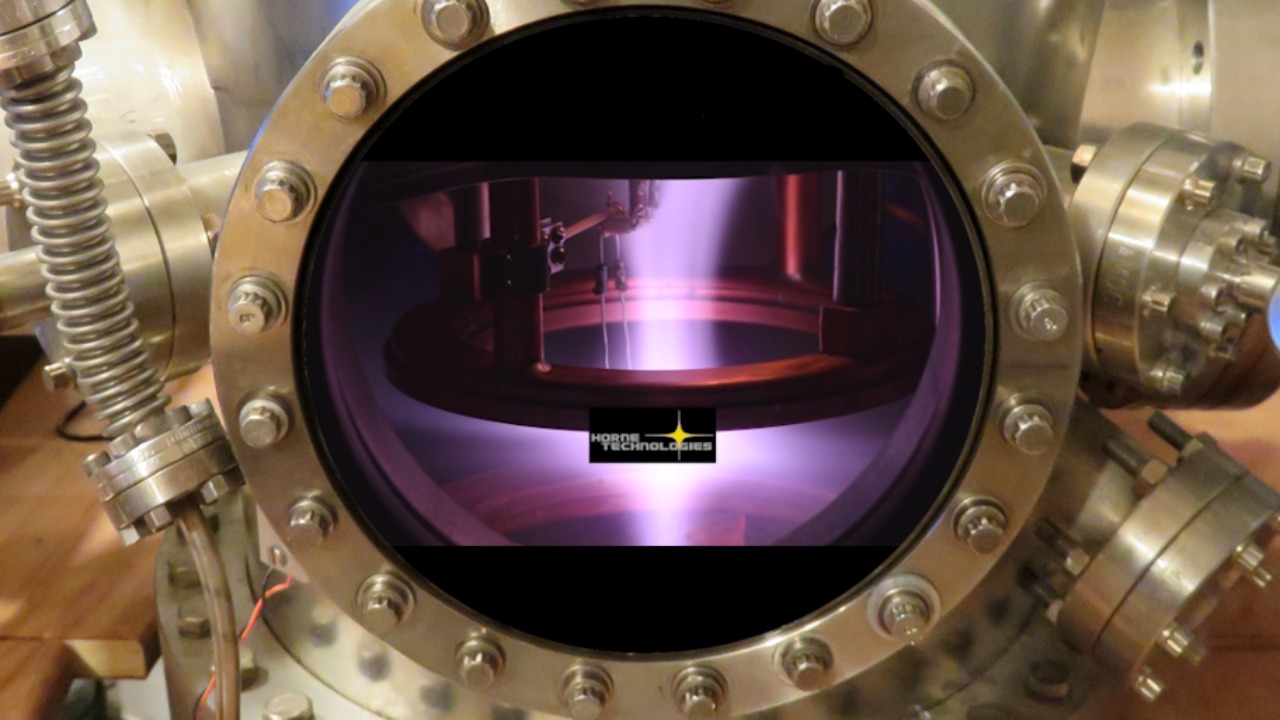

To understand how a fusion device could generate dark sector particles, it helps to look at the engineering of a modern tokamak. In a deuterium tritium reactor, a powerful magnetic field confines a plasma heated to tens of millions of degrees, hot enough for nuclei to overcome their mutual repulsion and fuse. Each fusion event releases energy in the form of fast neutrons and charged particles, and theorists argue that, if exotic fields couple even weakly to the plasma, some fraction of that energy could leak into new particles that stream out of the core almost unnoticed.

One of the most intriguing components in this picture is the so called breeding blanket that surrounds the plasma chamber. In many designs, that blanket is loaded with lithium so that the fast neutrons from fusion can generate fresh tritium fuel, allowing the reactor to sustain itself. A recent analysis of fusion and dark matter emphasizes that the reactor can use that tritium to fuel itself further, and that it is called a breeding blanket because it “breeds” tritium, but the same structure could also serve as a target where exotic particles deposit energy or convert back into detectable radiation. That dual role, described in detail in a report on how fusion reactors might create dark matter particles, is what turns a power system into a potential dark matter machine.

Real world reactors: from KSTAR to commercial concepts

The theory does not live in a vacuum, it is explicitly framed around existing and planned fusion devices. One flagship example is The KSTAR nuclear fusion reactor, a superconducting tokamak that has already demonstrated long pulse, high temperature plasmas. In the new dark matter proposals, KSTAR and similar machines are treated as testbeds where researchers can plug in additional diagnostics, such as neutron monitors and calorimeters in the blanket, to look for tiny deviations from expected energy flows that might hint at exotic particle production.

More broadly, the same studies argue that any future commercial plant built around deuterium tritium fuel could, in principle, be instrumented for dark sector searches at relatively low cost. The central idea is simple, the fusion reactions that power the plant also provide a controlled, repeatable environment for new physics, and the surrounding structures can double as detectors. That logic is laid out in coverage that notes how fusion reactors may be the key to uncovering dark matter and singles out Fusion devices like The KSTAR as examples of platforms where this dual use approach could be tested, a point emphasized in an analysis of fusion based dark matter searches.

A fusion puzzle solved, and what it means for axions

While theorists sketch out how reactors might emit dark sector particles, plasma physicists are wrestling with the practical challenges of keeping a fusion device stable and efficient. One recent breakthrough story centers on a physicist who tackled a long standing problem in fusion reactor design that had even been referenced in a sitcom plotline. By reexamining how certain instabilities grow in the plasma and how magnetic fields can be tuned to suppress them, this researcher proposed a solution that could make steady state operation more realistic.

That same work is closely tied to axion physics, since the improved understanding of plasma behavior feeds directly into models of how axions or similar particles might be produced and escape. A detailed report on this effort describes it under the banner of “Investigating axions,” and reiterates that, unlike normal matter, dark matter does not absorb or reflect light, which is why any axion signal would have to be inferred from missing energy or subtle distortions in the plasma. The article notes that scientists know it exists from its gravitational effects, but they are now exploring whether a fusion reactor that solves its own stability issues could also become a precision probe of the dark sector, a connection drawn explicitly in coverage of how Investigating axions intersects with fusion engineering.

When television scripts meet real fusion theory

The overlap between pop culture and cutting edge physics is not just a curiosity, it has shaped how some of these ideas reached the public. A recent commentary traces how a real physics paper inspired a fictional episode in which two characters finally crack fusion energy on a whiteboard, complete with equations that mirror actual research. In that discussion, the author notes that this is a common trope, where complex theories are smuggled into mainstream entertainment as background jokes, but in this case the math on screen tracked closely with real models of plasma confinement and energy extraction.

That same piece uses the episode as a jumping off point to explain what axions are, describing them as Hypothetic particles that could solve multiple problems at once if they exist. Under the heading “What are Axions?,” the commentary walks through how these Hypothetic fields might be produced in stars, in the early universe, or in fusion plasmas, and why they are so hard to detect. By tying a fictional breakthrough to a real research agenda, the analysis shows how a television script about solving fusion can echo the genuine scientific push to link reactors and dark matter, a connection unpacked in detail in a feature on What Axions mean for fusion.

What experiments inside reactors might actually look for

If fusion plants are to double as dark matter laboratories, experimentalists will need concrete observables to chase. One obvious target is missing energy: if a fraction of the fusion output vanishes into invisible particles, the measured heat and neutron flux in the blanket will not quite add up to the theoretical prediction. That requires extremely precise accounting of every joule, from the plasma core to the cooling loops, and careful modeling of mundane losses so that any residual discrepancy can be trusted as a hint of new physics rather than a calibration error.

Another strategy is to look for secondary effects when exotic particles interact with the breeding blanket or surrounding structures. For example, if axion like particles convert into photons in a magnetic field, or if exotic scalars scatter off nuclei in a distinctive way, specialized detectors embedded in the reactor walls could pick up those signals. The theoretical work tied to the DOI 10.1007/JHEP10(2025)215 outlines how such signatures might scale with plasma temperature and density, giving engineers a roadmap for where to place sensors and what energy ranges to monitor. In practice, that means future fusion facilities could be designed from the ground up with dual roles in mind, balancing the demands of power generation with the subtle requirements of high energy particle searches.

The stakes if fusion really can forge the universe’s missing matter

If these ideas pan out, the implications would ripple far beyond the fusion community. A confirmed detection of dark sector particles emerging from a reactor would instantly elevate such facilities into the same league as flagship particle accelerators, but with the added benefit of producing usable electricity. That dual payoff could reshape funding priorities, encouraging governments and private investors to treat fusion plants as multi purpose scientific instruments rather than just power stations, and giving dark matter research a new, more applied justification.

There is also a conceptual payoff. For decades, the search for dark matter has been split between astrophysical observations on the largest scales and particle experiments on the smallest. Using fusion reactors as dark matter factories would literally bring the cosmos into the lab, letting physicists study processes that once occurred only in the first fractions of a second after the Big Bang. Even if no new particles are found, the effort to instrument reactors for such delicate measurements will sharpen our understanding of plasma physics and reactor design, feeding back into the broader push to make fusion a practical part of the energy mix while keeping the door open to discoveries that could rewrite our picture of the universe.

More from MorningOverview