The discovery of a vast, fresh impact scar on Mars began with what looked like a smudge in a routine weather snapshot. A camera built to monitor daily clouds and dust storms ended up flagging the largest new crater ever confirmed on the Red Planet using before and after images. That stroke of luck, backed by meticulous follow up work, has turned a simple “weathercam” into one of the most powerful tools for catching Mars in the act of changing.

I see this impact as a turning point in how we watch other worlds: a reminder that planetary surfaces are not static postcards but living records of violent events. By tracing how a single dark blotch in a global weather map led to a crater roughly half a football field across, researchers have opened a sharper window into Mars’s hazards, its hidden ice, and even the way artificial intelligence might soon comb the planet for the next big blast.

From faint smudge to record breaker

The story starts with a daily global image sequence that was never meant to chase meteoroids. The Mars Color Imager, known as MARCI, rides aboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter and was designed to deliver continuous weather reports for Mars, the Red Planet, rather than to hunt for fresh scars. Yet in one of those routine frames, a mission scientist noticed a new dark patch that had not been present in earlier passes, a subtle sign that something explosive had happened on the surface between two orbits.

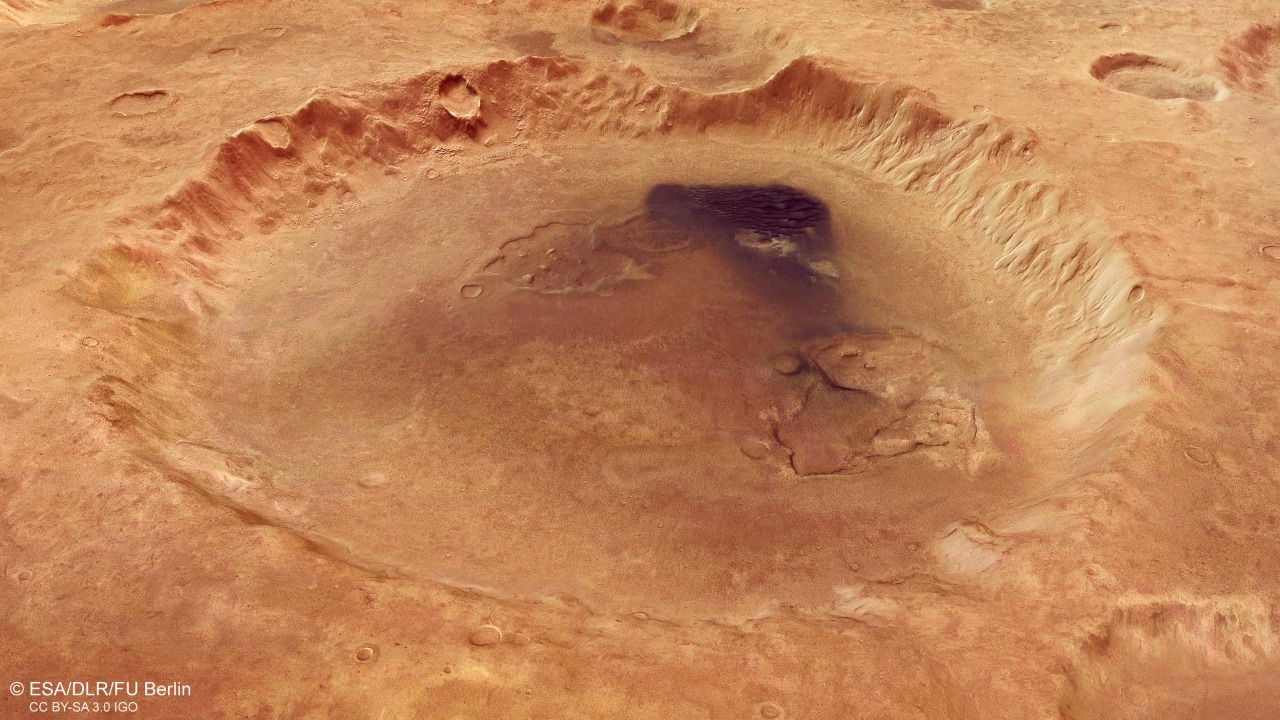

When researchers dug into the data, they realized that this was not just any new feature but the largest fresh meteor impact crater ever firmly documented on Mars with before and after pictures. Follow up imaging showed that the main cavity was slightly elongated and spanned 48.5 by 43.5 meters, roughly half the length of a football field, surrounded by a blast zone of darkened terrain and secondary pits. That scale instantly set it apart from the hundreds of smaller impacts that had been cataloged before.

What the Mars WeatherCam actually sees

To understand why this find was so surprising, it helps to look at how the “weathercam” works. The Mars Color Imager is a wide angle camera that sweeps out daily global mosaics of Mars, capturing the evolution of clouds, dust storms, and seasonal hazes as the Reconnaissance Orbiter circles the planet. Its job is to keep a continuous eye on the atmosphere so that other instruments can plan their high resolution shots and so that scientists can build long term climate records for the Red Planet.

Those global views are processed and archived by teams at Malin Space Science Systems, the company that built MARCI and several other Mars cameras. On any given sol, the instrument produces a kind of “Red Planet weather report” that mission planners and researchers can browse through on Malin’s image portal. The fresh crater only appeared because that daily cadence is relentless: when a new dark blotch suddenly interrupted an otherwise familiar landscape, it stood out against the backdrop of slowly shifting clouds and dust.

Pinpointing the impact with sharper eyes

Once the dark scar was flagged in the weather data, the hunt shifted to higher resolution instruments. The Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter carries a Context Camera that can zoom in on specific regions at much finer detail than MARCI, and it was quickly tasked to image the suspicious site. The resulting view revealed a sharply defined impact structure in Amazonis Planitia, with a central pit, bright ejecta rays, and a halo of darker material that confirmed a recent blast rather than an ancient relic.

That intermediate scale view, captured by the Context Camera in Amazonis Planitia, gave scientists the confidence to call in the sharpest imager in Mars orbit, the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment. HiRISE images showed the crater’s elongated shape, the pattern of secondary craters, and the way the ejecta had excavated subsurface material, all of which helped reconstruct the trajectory and energy of the incoming meteoroid. In effect, the discovery moved from a blurry weather snapshot to a forensic close up, each camera tightening the constraints on what had happened.

How big blasts reshape Mars’s surface

Fresh impacts like this are not just curiosities, they are active agents of change on Mars. When a meteoroid slams into the ground at high speed, it excavates material from depth, lofts it into the thin air, and sprays it across the surrounding terrain as a blanket of ejecta and secondary craters. In the case of this record setting blast, the dark halo around the main pit showed that darker subsurface material had been dredged up and spread over a wide area, altering the local albedo and even the way the surface warms and cools each day.

Over time, these events accumulate into a kind of geological clock. Mars orbiters have already located about 400 fresh impacts that have been confirmed with before and after images, each one a timestamp on the planet’s recent history. The fact that this particular crater is so large, yet still young enough to be caught in the act, gives researchers a rare calibration point for how often big meteoroids hit Mars and how quickly its surface is being churned and resurfaced.

Clues to hidden ice and subsurface layers

One of the most intriguing aspects of the giant crater is what it reveals about what lies beneath the Martian dust. High resolution images showed bright patches within the ejecta that researchers interpret as excavated ice, suggesting that the impact punched through a dry surface layer into a reservoir of frozen water. In video briefings, scientists using the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter have emphasized that such craters act like accidental drill holes, exposing subsurface water ice that would otherwise remain hidden.

That matters for more than just curiosity. Knowing where subsurface ice exists on the planet helps mission planners identify potential landing sites for future robotic and crewed missions, since buried ice can be a resource for water, oxygen, and fuel. The fresh crater’s location and the apparent depth of excavation give a direct measurement of how shallow that ice is in this region, complementing other orbital data sets and tying them to a specific, well characterized event. In that sense, the Mars WeatherCam did more than spot a hole in the ground, it helped map a potential lifeline for future explorers.

Listening to impacts as marsquakes

The visual drama of a new crater is only part of the story, because big impacts also shake the planet like natural seismic experiments. When a meteoroid struck Mars on 24 December 2021, the InSight lander registered vibrations equivalent to a magnitude 4.0 marsquake, and later satellite images revealed a 150 kilometer wide dust cloud and a fresh crater at the impact site. That event showed how impacts can serve as controlled sources for probing the Martian interior, with seismic waves that travel through the crust and mantle before returning to the surface.

InSight’s seismometer data, combined with orbital imaging of the resulting crater, allowed researchers to tie a specific seismic signal to a known impact, improving models of how seismic waves move through Martian rock. A similar synergy applies to the giant crater first flagged by the weather camera, even if no lander happened to be listening at the time. Each new impact that can be both seen and, in some cases, heard adds another calibration point for understanding Mars’s internal structure and the mechanical properties of its crust.

How scientists confirmed the record

Turning a suspicious smudge into a confirmed record breaker required a careful chain of evidence. Researchers first used the MARCI time series to bracket when the dark scar appeared, narrowing the impact window to a period of just a few days. Then they pulled in Context Camera and HiRISE images to measure the crater’s dimensions, map the ejecta, and check for signs of dust deposition that might have obscured older features. Only after that multi instrument review did they feel confident calling it the largest fresh meteor impact crater yet documented with before and after images.

Mission teams have described how researchers on the Red Planet science campaigns routinely scan MARCI frames for such anomalies, even though the camera’s primary role is atmospheric. In this case, the workflow paid off spectacularly, and the discovery was later highlighted in a dedicated Mars Weathercam Helps Find Big, New Crater feature that walked through the chain of observations. The process underscores how a seemingly modest instrument can punch above its weight when paired with a disciplined search strategy.

A growing catalog of fresh scars

The giant crater sits within a much broader effort to track Mars’s ongoing bombardment. Over the past decade, teams have used MARCI, the Context Camera, and other instruments to build a catalog of fresh impact scars, each one confirmed by comparing new images to older baselines. The impact scar detected in a Mars Weathercam image that led to this record crater is part of that tally, which now includes hundreds of events of varying sizes and morphologies scattered across the planet.

Some of these scars are only a few meters across, barely visible even in high resolution frames, while others, like the Amazonis Planitia blast, are large enough to be picked up in low resolution global views. A separate analysis of a fresh Mars crater confirmed within an impact scar noted that this event is the only one so far big enough for the scar to be first detected in MARCI images, which highlights just how unusual it is. As the catalog grows, scientists can refine estimates of how often Mars is hit, how impact rates vary by region, and how quickly the surface darkens or brightens again as dust settles.

AI joins the hunt for Martian craters

Human eyes have been central to these discoveries, but artificial intelligence is starting to take on more of the heavy lifting. In a recent project described as Scanning the Martian Surface In October, NASA scientists trained a machine learning system to sift through orbital images and flag potential new craters on Mars. The AI successfully identified its first fresh impacts, which were then confirmed by human analysts, showing that automated tools can spot subtle changes that might otherwise be missed in the flood of data.

For a record setting crater like the one found by the weather camera, AI could have accelerated the initial detection, catching the dark scar as soon as it appeared in the global mosaic. As the volume of imagery grows with each passing year, I expect such systems to become standard, scanning for new dark spots, ejecta patterns, or dust plumes in near real time. The combination of human intuition, honed by years of staring at Mars, and machine pattern recognition, tireless and systematic, will make it harder for any big impact to slip by unnoticed.

Why this crater matters for future missions

Beyond the scientific intrigue, the giant fresh crater carries practical implications for how we explore Mars. The event is a reminder that the planet is still being bombarded by space rocks, some of them energetic enough to carve out cavities tens of meters across and to loft debris over wide areas. For engineers designing landers, rovers, and eventually habitats, understanding the current impact environment is essential for assessing risk, choosing safe landing zones, and planning how to shield critical infrastructure.

The crater’s apparent excavation of subsurface ice also feeds directly into mission planning. If a single impact can expose bright ice at shallow depth, then drilling or trenching operations at similar latitudes might reach usable water with relatively modest equipment. That prospect has already influenced discussions of where to send future robotic scouts and, eventually, human crews, who will need reliable in situ resources to sustain long stays on the surface. In that sense, the Mars WeatherCam’s serendipitous find is not just a scientific milestone but a quiet enabler of the next phase of exploration.

A camera built for weather, reshaping geology

What strikes me most about this story is how a camera built for one purpose has transformed another field entirely. The Mars Color Imager was conceived as a meteorological tool, a way to track dust storms and clouds so that other instruments could operate safely and efficiently. Yet by providing a continuous, global baseline, it has become a powerful detector of change, sensitive to any new dark or bright feature that appears on the surface from one pass to the next.

Profiles of The Mars Color Imager, MARCI, on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter have emphasized its role in building a “Red Album” of daily weather reports, but the giant crater shows that its legacy will also be written in rock. By catching the largest fresh impact crater ever documented with before and after images, the weathercam has blurred the line between atmospheric science and geology, proving that sometimes the most transformative discoveries come from instruments quietly doing their routine jobs, day after day, until something extraordinary appears in the frame.

How the story reached the public

Once the scale of the crater became clear, mission teams moved quickly to share the discovery with the public. Detailed write ups explained how NASA’s Mars Weathercam helps find big new craters, walking readers through the sequence from MARCI detection to high resolution confirmation. A companion video titled Mars Weathercam Helps Find Big, New Crater featured scientists explaining how they used the HiRISE camera to zoom in on the site and what the exposed ice might mean for subsurface water on the planet.

Coverage spread quickly, with pieces such as Mars Weathercam Spots Big New Crater and analyses comparing the blast’s energy to events like the Chelyabinsk airburst, which one report described as “roughly on par with a modern nuclear bomb” in the Los Angeles Times. Visual galleries such as huge Mars crater photos and a video featuring Scientists using NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter helped audiences grasp the scale of the event, turning a once obscure weather instrument into a headline making star.

More from MorningOverview