A strange cosmic blast that lit up the sky in two distinct acts is forcing astronomers to rethink how stars live and die. The event, tagged AT2025ulz, appears to be the first known case where a massive star exploded, left behind a pair of ultra dense remnants, then produced a second, different kind of explosion when those remnants collided. I see researchers converging on a provocative label for this double detonation, a “superkilonova,” while openly admitting that the physics behind it is still not fully understood.

The bizarre signal that started it all

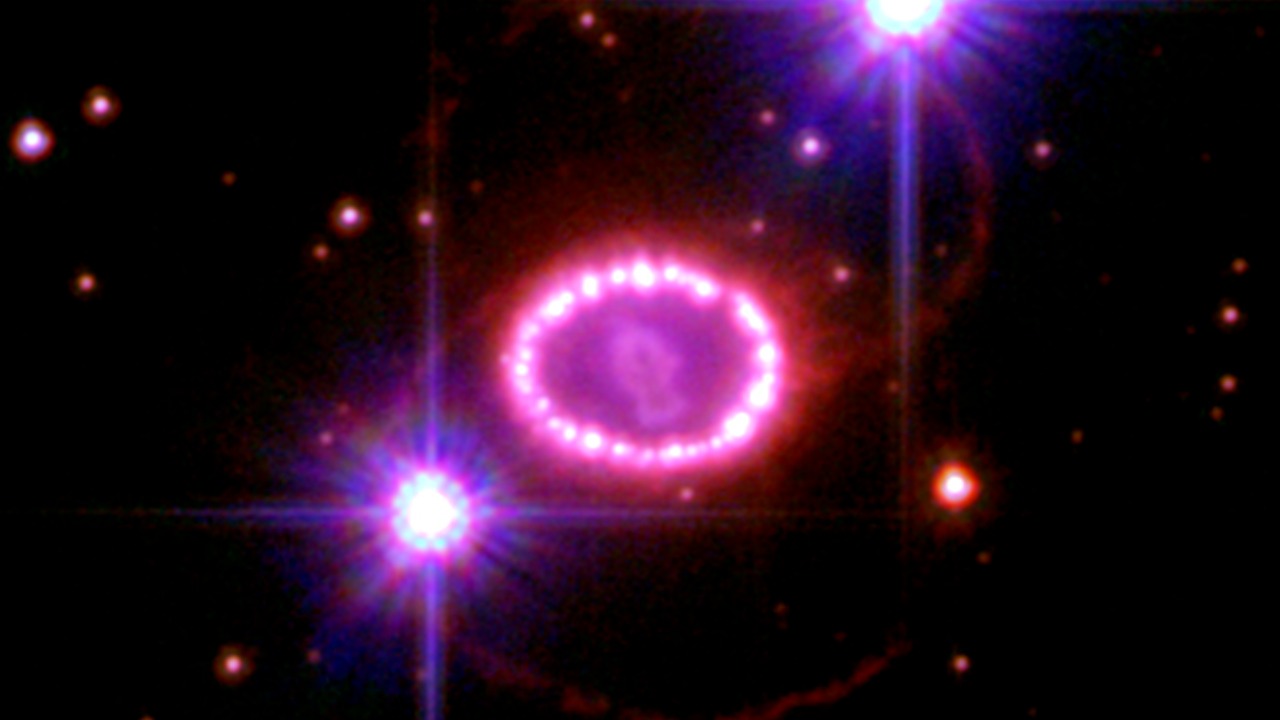

The story began with a ripple in spacetime. Earlier this year, gravitational wave detectors picked up a compact binary merger that looked like two neutron stars spiraling together, a pattern that usually heralds a kilonova. Within hours, telescopes around the world swung toward the patch of sky where the signal pointed and found a rapidly evolving optical transient that would later be cataloged as AT2025ulz, a sequence described in detail in accounts of how observers reacted Seeing Red, Then Blue.

At first glance, the light looked like a fairly ordinary stellar death. The source flared with an intense red glow that brightened and faded quickly, behavior that strongly resembled a stripped envelope supernova in which a massive star has already shed most of its outer layers. Reports on the AT2025ulz light curve note that this early phase matched expectations for a Type IIb style blast, the kind of event that Dec and other Astronomers have long associated with stars that have lost much of their hydrogen before collapsing, a comparison that underpins the initial classification in detailed write ups of the Type IIb stripped envelope supernova.

When a “normal” supernova refused to fade

Then the script broke. Instead of fading away as a typical supernova would, AT2025ulz did something that left observers scrambling to check their instruments. After the red light dimmed, the source began to brighten again, this time shifting toward bluer wavelengths and evolving much faster than a standard stellar explosion. Analyses of the event emphasize that, instead of following the familiar decline of radioactive nickel decay, the luminosity curve reversed course, a twist highlighted in discussions that open with the phrase Instead of fading as astronomers typically expect.

Follow up observations captured this second act in multiple colors, revealing a hotter, more compact source that brightened and dimmed on a timescale of days rather than weeks. Spectra taken during this phase lacked the broad hydrogen features of the first explosion and instead showed signatures more consistent with the merger of two neutron stars, the kind of event that usually powers a kilonova. Teams tracking the object reported that this blue component lined up in time and position with the earlier gravitational wave signal, a coincidence that strengthened the case that the two flashes were physically linked, a connection that observers describe when they note how telescopes responded Within hours of the gravitational wave alert.

Why astronomers coined “superkilonova”

To make sense of this two stage performance, theorists reached for a new label. A standard kilonova is powered by the collision of two neutron stars, which eject neutron rich debris that rapidly builds heavy elements and glows as those freshly minted atoms decay. Here, though, the kilonova like signal appeared to be nested inside the aftermath of a recent supernova, with the first blast creating the compact objects that later merged. That stacked sequence led several teams to propose the term “superkilonova” for a scenario in which a massive star explodes, splits into two dense remnants, and then produces a second explosion when those remnants collide, a chain of events laid out in detail in descriptions of a possible superkilonova exploded not once but twice.

In technical papers and conference talks, Dec and other Astronomers argue that this hybrid event sits at the intersection of two well studied phenomena, yet does not fit neatly into either box. The first explosion behaves like a stripped envelope core collapse, while the second resembles a compact binary merger, but the timing and environment tie them together in a way that had only been theorized. One summary of the work notes that, after detecting this strange combination of signals, researchers realized they might be seeing a phenomenon that had been predicted but never observed, a point underscored in analyses that describe how teams, after detecting a strange combination of gravitational waves and light, proposed a new category they explicitly call a superkilonova.

Reconstructing a star that died twice

Piecing together what happened to the progenitor star is like working backward from a crime scene. The leading model starts with a very massive star that had already lost most of its outer layers, perhaps through winds or interaction with a companion, leaving behind a compact core primed for collapse. When that core ran out of fuel, it imploded and then rebounded in a supernova, ejecting the remaining envelope and briefly lighting up as the red transient that first drew attention to AT2025ulz, a sequence that matches the early time behavior described in reconstructions of how a massive star may have burst and left behind two dense, dead cores before the merging of two objects produced another explosion, a chain laid out in reports on how In a First, Astronomers May have witnessed such a rare double event.

In this picture, the collapsing core did not form a single neutron star or black hole. Instead, it fragmented into two compact objects, a configuration some theorists call “forbidden” because it is difficult to produce in standard stellar evolution models. These twin remnants then orbited each other inside the expanding debris, gradually losing energy through gravitational waves until they finally merged, triggering the second, kilonova like explosion. One detailed discussion quotes a researcher explaining that if these “forbidden” stars pair up and merge by emitting gravitational waves, such an event could naturally produce a superkilonova, an argument that is spelled out in analyses that ask whether astronomers saw a star explode twice and note that “If these ‘forbidden’ stars pair up and merge by emitting gravitational waves, it is possible that such an event would produce a superkilonova.”

What the light revealed: red, then blue

For me, the most striking part of the data is how clearly the color evolution traces this two step story. In the first days after the gravitational wave alert, AT2025ulz glowed a deep red and faded quickly, behavior that lined up with models of a stripped envelope supernova powered by radioactive decay in expanding, cooling ejecta. Observers described this phase as “seeing red,” a label that captures both the literal color and the sense that the event initially looked familiar, a framing that appears in accounts that explicitly title this early stage Seeing Red, Then Blue to emphasize the dramatic shift that followed.

As the red light faded, a bluer, hotter component emerged and brightened, consistent with a more compact source of energy such as the radioactive decay of heavy r process elements in neutron rich ejecta. This second phase evolved more rapidly and showed spectral signatures that differed from the initial supernova, supporting the idea that a separate physical process had kicked in. Detailed photometry and spectroscopy of this blue component convinced many teams that the second explosion was not simply a quirk of the original blast, but a distinct kilonova like event layered on top of the supernova, a conclusion that underlies the argument that the first flare may have been a supernova instead of a kilonova and that only the later blue light truly matches a compact merger, a distinction drawn in analyses that weigh whether the early red signal could have been a supernova instead.

Gravitational waves, heavy elements, and cosmic alchemy

Beyond the fireworks, AT2025ulz matters because it ties together several of the biggest questions in modern astrophysics. Gravitational wave detectors have opened a new window on compact object mergers, but connecting those ripples to specific light sources has been challenging. In this case, the close match between the merger signal and the blue kilonova like flare gives researchers a rare chance to study the full life cycle of a system that went from massive star to double neutron star to final collision, a chain that Dec and other Astronomers highlight when they describe how the neutron stars spiral together and collide, unleashing a kilonova whose light can be traced back to an earlier supernova, a narrative laid out in explanations that begin with the phrase The neutron stars spiral together and end with the suggestion that maybe this was the first such event ever seen.

The event also speaks directly to the origin of the heaviest elements in the Universe. Kilonovae are thought to be major factories for gold, platinum, and other r process elements, the same ingredients that end up in electronics and in the silver in your jewelry box. By catching what may be the first example of a supernova that quickly produced a neutron star pair and then a kilonova, observers can test how efficiently such systems synthesize heavy nuclei. One detailed account notes that By Robert Lea and others, researchers emphasize that while they do not know with certainty that they found a superkilonova, the event could help explain where the gold, platinum, and silver in your jewelry box came from, a connection that is drawn explicitly in discussions of how By Robert Lea and colleagues interpret the heavy element yields.

A stress test for supernova and kilonova theory

From a theoretical standpoint, AT2025ulz is a stress test for models that had grown comfortable. Before this event, astronomers thought they knew what to expect from a kilonova, a rare cosmic explosion sparked by the collision of two neutron stars in an old binary system that had been orbiting quietly for millions or billions of years. The idea that a massive star could explode, split into two small remnants, and then produce a kilonova like merger on a timescale of days or weeks forces modelers to revisit assumptions about how quickly such systems can form and coalesce, a challenge that is spelled out in summaries that note how Astronomers thought they knew what to expect from a kilonova and then had to confront evidence that it could be born inside a fresh supernova, a tension described in analyses that open with the phrase Astronomers thought they knew what to expect.

The event also intersects with broader cosmological measurements. Neutron star mergers can serve as “standard sirens” for measuring cosmic expansion, complementing traditional distance ladders based on supernovae and the Universe Cosmic Microwave Back background. One line of research, for example, reports a measurement of ~75.7 km/s/Mpc for the Hubble constant using local distance indicators, compared with measurements (~73 km/s/Mpc) inferred from early Universe Cosmic Microwave Back radiation and CMB analyses, a discrepancy that has become known as the Hubble tension and has been spurring new observations and theories, a context laid out in technical work that details how this measurement of ~75.7 km/s/Mpc. measurements (~73 km/s/Mpc), Mpc, Universe Cosmic Microwave Back, CMB compare. Events like AT2025ulz, which combine gravitational waves and electromagnetic signals, could eventually refine these measurements by providing independent distance estimates tied directly to the physics of compact mergers.

Why some astronomers remain unconvinced

Despite the excitement, not everyone is ready to declare AT2025ulz the first confirmed superkilonova. Some researchers argue that the data could still be explained by an unusual supernova interacting with dense circumstellar material, or by a magnetar powered explosion that injected extra energy into the ejecta at late times. Others point out that the gravitational wave signal, while suggestive, is not pinpointed with the same precision as the famous GW170817 event, leaving room for alternative interpretations of the link between the merger and the optical transient, a caution that surfaces in discussions that ask more generally whether astronomers saw a star explode twice and weigh competing models for the did astronomers see event.

Even among proponents of the superkilonova label, there is a recognition that this is a working hypothesis, not a settled fact. One detailed narrative notes that Dec and other Astronomers may have detected a first of its kind superkilonova, but they are careful to frame it as a candidate rather than a definitive discovery, emphasizing the need for more examples and better theoretical modeling. That cautious tone runs through reports that describe a novel astronomical event, termed a “superkilonova,” proposed to explain the coincident detection of a gravitational wave signal and a peculiar optical transient, a framing that appears in summaries that state that Astronomers may have detected a first of its kind Astronomers may have detected such an event but stop short of claiming certainty.

What comes next for “double blast” astronomy

For me, the most immediate consequence of AT2025ulz is a shift in how observers respond to future gravitational wave alerts. Instead of assuming that a compact merger must come from an old, quiet binary, teams will now be watching for signs that a recent supernova may have set the stage. That means combing archival survey data for earlier outbursts in the same region and designing follow up campaigns that can catch both the red and blue phases of any potential double explosion, a strategy that is already being discussed in accounts that describe how a double cosmic explosion gives birth to an unprecedented “Superkilonova” and how observers will be looking for similar patterns in future events, a perspective laid out in analyses that frame AT2025ulz as a Double Cosmic Explosion Gives Birth scenario.

Theoretically, the event is already inspiring new simulations of how a collapsing core might fragment into two compact objects and how quickly those remnants could merge inside expanding debris. Some models explore whether strong magnetic fields or rapid rotation could drive the core to split, while others test how different mass ratios affect the timing and brightness of the second explosion. As Dec and other Astronomers refine these calculations, they will be looking for clear observational signatures that can distinguish a true superkilonova from a more mundane supernova or kilonova, a process that is being framed in outreach pieces that playfully ask whether an event is a kilonova, a supernova, or something in between and suggest that maybe this was the first, a theme captured in explanations that open with the line maybe this was the first such hybrid explosion.

More from MorningOverview