AlphaFold arrived as a technical moonshot that suddenly made protein structures feel like software rather than secrets of nature, and five years on it has rewired how laboratories plan experiments, share data, and even imagine new medicines. What began as a breakthrough in predicting how amino acid chains fold has become a living infrastructure for biology, with new models, databases, and rival systems pushing the field forward. The story now is less about a single algorithm and more about how an entire ecosystem of tools, norms, and expectations is evolving around it.

From grand challenge to everyday lab tool

For decades, predicting how a protein’s amino acid sequence folds into a three‑dimensional shape was treated as a grand challenge, something that required years of crystallography or cryo‑electron microscopy for each structure. AlphaFold changed that by turning structure prediction into a computational problem that could be run on demand, so a question that once stalled projects for months could be answered in hours. The original AlphaFold 2 system was quickly recognized as a landmark in computational biology, and its technical achievement was formally documented in Nature, where the work was credited to a team under the leadership of the AlphaFold project.

That shift did not just impress peers, it reset expectations for what artificial intelligence should deliver in the life sciences. Deep learning models were no longer just pattern recognizers for images or language, they were now engines that could infer the physical behavior of matter at the molecular scale. In a public conversation about the project, researcher John Jumper framed the stakes in very concrete terms, describing how a mutation in a protein might be a cause of infertility and how understanding that structure could point to treatment ideas, a perspective he shared in a Google Deep talk that underscored the clinical implications of what might otherwise sound like abstract geometry.

Opening the vault: a public atlas of proteins

The real inflection point came when the predictions stopped being a proprietary curiosity and became a public resource. Instead of keeping the system’s output behind closed doors, the team released a vast online repository of structures that any researcher could browse or download. That resource, now known as the AlphaFold database, turned the model’s predictions into a kind of molecular atlas, so a lab studying a rare enzyme or viral protein could look up a plausible 3D model before ever stepping into a beamline facility.

The database has not stood still either, it has been updated in lockstep with reference protein catalogs so that it remains relevant as biology’s own naming and annotation systems evolve. A major update described as AlphaFold DB v6 brought the resource into sync with UniProt and expanded it to 214,000,000 protein structures, including 40,054 isoforms, a scale detailed in the Tue release notes. That kind of coverage means that for many organisms, from model species to pathogens, a predicted structure is now just a search query away.

Five years of impact, by the numbers

Once the predictions and database were in place, the question shifted from “can this work” to “what does it change.” Since 2020, AlphaFold has accelerated the pace of science and fueled a global wave of biological discovery, a claim that is not just marketing but is backed by the volume of structures solved in silico and the number of projects that now start from a predicted fold rather than a blank slate. DeepMind has described how the system has helped researchers bypass years of expensive, painstaking experimental work by providing high quality starting models, a point it highlights in its Since retrospective on the project’s scientific impact.

Independent analyses have tried to quantify that shift, tracking how often AlphaFold predictions appear in papers, patents, and grant proposals. Charts compiled to mark the system’s fifth anniversary show a steep rise in citations and usage across structural biology, genomics, and even fields like plant science. Part of AlphaFold2’s rapid impact is down to its accessibility, with researchers pointing out that Google DeepMind made the underlying code and many of the predictions freely available, a decision that is credited in a Part of analysis that links openness to the breadth of downstream work now visible in the literature.

How AlphaFold reshaped drug discovery

The most immediate practical payoff has been in drug discovery, where knowing the shape of a target protein is often the first bottleneck in designing a molecule that will bind to it. Instead of waiting for a crystal structure, medicinal chemists can now pull a predicted fold and start docking candidate compounds in silico, pruning the search space before they ever synthesize a single molecule. Commentators at ELRIG’s Drug Discovery 2025 meeting in Liverpoo described AlphaFold’s impact on the research world as astronomical and framed it as a cornerstone of an “AI‑first” approach to designing medicines, a sentiment captured in a Drug Discovery feature that traces how structural predictions are now woven into early screening campaigns.

Concrete case studies are starting to appear in the peer‑reviewed literature. One example is the efficient discovery of a novel CDK20 small molecule inhibitor, where artificial intelligence was used to prioritize compounds that were then synthesized and tested in biological assays. The authors of that work describe the application of AI as a revolutionary change in drug discovery and development, and their Abstract makes clear that structural modeling was central to narrowing down which molecules were likely to fit the CDK20 binding pocket. While not every such project relies directly on AlphaFold, the broader pattern is that structure prediction has moved from a luxury to a routine step in designing new therapeutics.

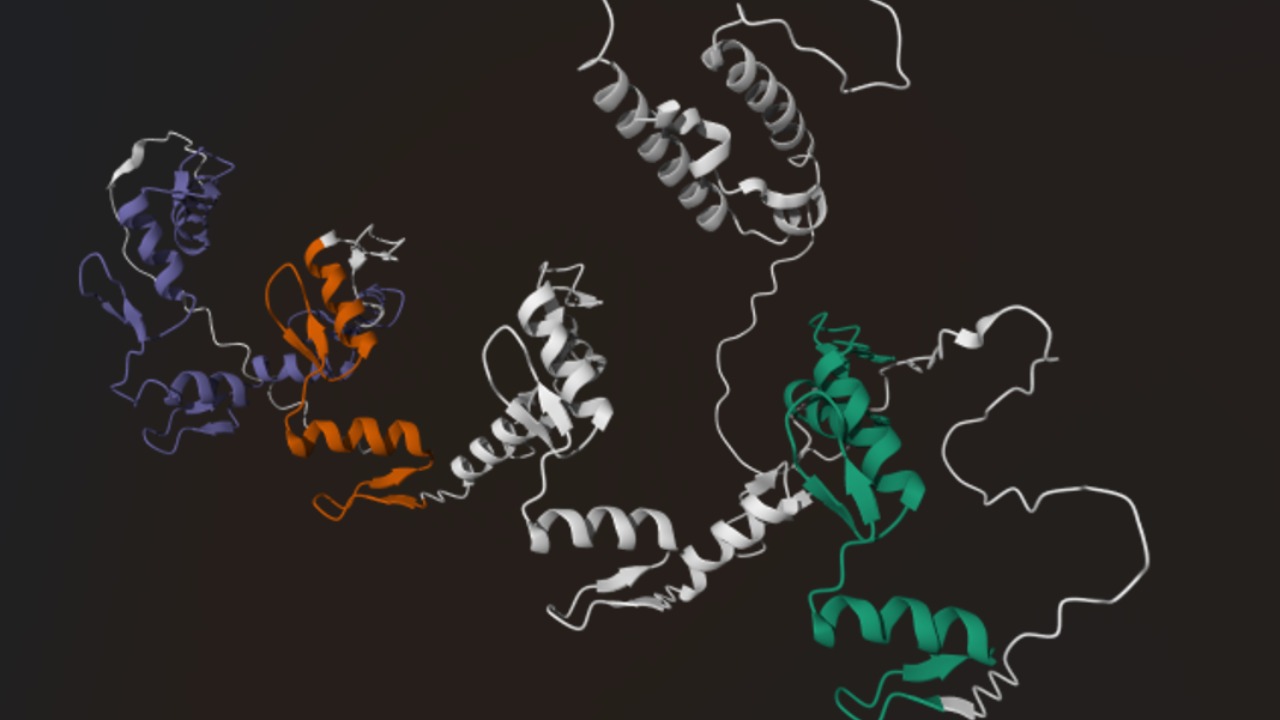

Beyond proteins: toward whole‑cell chemistry

As powerful as protein structure prediction is, biology does not stop at single chains of amino acids. Cells are crowded with complexes, membranes, nucleic acids, and metal ions, and the next wave of models is trying to capture that richer chemistry. AlphaFold’s newer iterations and related tools are being applied to protein complexes and interactions, helping researchers understand how multiple chains assemble and how they might be disrupted or stabilized by drugs. Reporting on the engineering behind the system has emphasized that AlphaFold’s significance goes beyond awards and accolades, noting that it has sped up drug discovery by producing high quality structures of proteins and their complexes with other molecules, including ligands, DNA, and metal ions, a point highlighted in a But deep dive into the model’s capabilities.

DeepMind has also started to position AlphaFold as part of a broader portfolio of AI systems that tackle different layers of biology, from genomes to proteomes to phenotypes. Related posts on its own channels describe projects like AlphaGenome, which aims for better understanding of the genome, and AlphaProteo, which generates novel proteins, situating AlphaFold as one component in a larger “Alpha” family of models. In its Related updates, the team connects these efforts to specific scientific stories, such as work published in Science that uses AI to reveal mechanisms behind disease or to engineer new biomolecules, signaling that the frontier is shifting from predicting what exists to designing what might work better.

Open rivals and the question of access

AlphaFold’s success has inevitably inspired competitors, particularly from groups that want fully open systems that can be used without licensing constraints. One prominent example is OpenFold3, an open‑source protein structure AI that aims to match the performance of AlphaFold3 while keeping the code and weights available for inspection and modification. Reporting on these efforts notes that OpenFold3 is part of a wider push to develop open‑source versions of AlphaFold3, and that while some of DeepMind’s models are accessible for academic use, they remain unavailable for commercial use, a tension described in an Open overview of the open‑source landscape.

This competition is not just ideological, it has practical consequences for startups, pharmaceutical companies, and public health agencies that want to build products on top of structure prediction. Fully open models can be embedded directly into commercial pipelines, while proprietary systems may require cloud access or licensing deals that shape who can innovate and at what cost. At the same time, the existence of strong open rivals pressures the original developers to keep improving performance and transparency, so the field as a whole benefits from a kind of constructive arms race in accuracy, speed, and interpretability.

What AlphaFold changed in the lab, and what it did not

One of the most striking cultural shifts is how quickly AlphaFold has become a default part of the experimental toolkit. In many labs, a predicted structure is now the starting point for mutagenesis experiments, antibody design, or functional annotation, and it is common to see figures that overlay an AlphaFold model with a partial experimental map. A detailed narrative on the system’s first five years notes that AlphaFold, DeepMind’s AI that predicts protein structures, has reshaped biology and chemistry and that its database is now used by the global research community, a perspective summarized in a Its account of how the tool moved from novelty to infrastructure.

Yet the same reporting and many researchers are careful to stress that AlphaFold has not ended experimental biology. Analyses of the field argue that the system has not replaced biological experiments but rather emphasized the need for them, perhaps AlphaFold2’s biggest impact has been to highlight where models are confident and where they are not, guiding scientists toward the most informative measurements. One thoughtful Perhaps essay on how AI revolutionized protein science but did not end it points out that the technology has shifted the balance of effort, freeing up experimentalists to focus on dynamics, interactions, and rare states that static models cannot yet capture.

From heart disease to honeybees: real‑world case studies

The abstract talk of folds and models becomes more tangible when you look at specific biological problems that have moved forward because of AlphaFold. One widely cited example involves revealing a key protein behind heart disease, where structural insight helped clarify how a particular molecule behaves and how it might be targeted therapeutically. Another case focuses on breeding healthier and stronger honeybees, where understanding the proteins involved in immunity and development can inform selective breeding and conservation strategies. These stories are highlighted in DeepMind’s own Revealing showcase of AlphaFold in action, which emphasizes how predicted structures help explain how proteins interact with other molecules throughout cells.

Such examples matter because they demonstrate that the technology is not confined to blockbuster drugs or elite research institutes. Agricultural scientists, ecologists, and public health teams are using the same tools to tackle problems as varied as crop resilience, vector‑borne disease, and environmental monitoring. The breadth of applications supports the claim, made by DeepMind cofounder Shane Legg and others, that AlphaFold did not just solve a scientific challenge but changed the tempo of discovery in ways that will ripple through society for decades to come, a sentiment he shared in a Nov reflection on the project’s fifth anniversary.

AI‑first medicine and the road ahead

Looking forward, many in the field expect AlphaFold and its successors to be central to a broader shift toward AI‑first medicine, where algorithms help design, test, and even personalize therapies before they reach patients. Commentators on health technology trends argue that the fusion of artificial intelligence and drug discovery has reached a new zenith and anticipate that in 2025 and beyond, we will witness AI systems that can predict how drugs will behave in the body, potentially reducing the need for some animal testing or even early‑stage clinical trials. That vision is laid out in a Living Long essay on tailored and smarter health, which treats structure prediction as one of several pillars in a new, more computational approach to medicine.

At the same time, practitioners are candid about the limits and open questions. A detailed feature on AlphaFold’s evolution notes that until AlphaFold’s debut in November, protein structure prediction was a painstaking craft, and that even now, understanding what makes us different genetically and what happens when DNA changes remains a frontier. If we can truly understand those differences, we unlock extraordinary possibilities for diagnosing and treating disease, but that will require integrating structural models with genomic, transcriptomic, and clinical data. As one DNA focused analysis puts it, AlphaFold is a step toward that future, not the endpoint.

Reimagining the drug pipeline, from lecture hall to clinic

The cultural impact of AlphaFold is visible not just in journals but in how the next generation of scientists is being trained. In classrooms and online lectures, instructors now walk students through workflows where you specify a protein, decide how you want a small molecule to fit, and then use AI tools to explore candidate compounds, rather than starting from trial‑and‑error wet lab work. One widely viewed presentation on a revolution in medicine uses exactly this framing, explaining that traditionally you would have to actually make and test each compound, whereas now AI can help you narrow the field dramatically, a point illustrated in an Aug talk on AlphaFold and drug design.

Industry strategists are already baking these assumptions into their pipelines. Commentators on AI‑first drug design argue that AlphaFold’s impact on the research world has been astronomical and that companies which fail to integrate such tools risk falling behind in both speed and cost. At ELRIG’s Drug Discovery 2025 in Liverpoo, speakers described a future where AI systems propose not just molecules but entire experimental campaigns, with human scientists acting more as curators and interpreters of model output. That vision aligns with broader trends in health technology, where predictive models are used to stratify patients, simulate trial outcomes, and personalize dosing, all of which depend on a deep, mechanistic understanding of proteins and their interactions that tools like AlphaFold help provide.

More from MorningOverview