Cold does not feel the same on your fingertips as it does deep in your chest, and new research shows that this is not just a matter of intensity or imagination. Scientists have now identified two distinct biological systems for sensing low temperatures, one tuned to the chill on the skin and another specialized for the cold that seeps into internal organs. The discovery helps explain everyday experiences, from the sting of an icy steering wheel to the shock of a freezing drink, and opens fresh paths for treating pain and respiratory disease.

Two flavors of cold: surface chill versus deep freeze

When I step outside on a winter morning, the cold that bites my cheeks feels very different from the ache that builds in my lungs after a few deep breaths of icy air. The latest work on cold perception argues that this split is not just psychological, it reflects two separate neural systems that track temperature in different parts of the body. One set of nerves monitors the skin and gives rise to the familiar sensation of coolness or frostbite risk, while another monitors organs such as the lungs and esophagus and signals a more visceral, internal cold.

Researchers describe these as two different cold sensors hiding in the body, each wired to its own circuits and tuned to distinct temperature ranges. In animal models, they found that the nerves serving the skin respond rapidly to modest drops in temperature, while those innervating internal tissues react more sluggishly but to deeper cooling, the kind you might feel after swallowing a very cold drink or inhaling frigid air. This split system, highlighted in new reporting on how the body feels cold in two different ways, helps explain why a cold surface, a blast of winter wind and a chilled beverage can all feel so unlike one another even when a thermometer would register similar degrees of cold.

Inside the experiments that separated two cold pathways

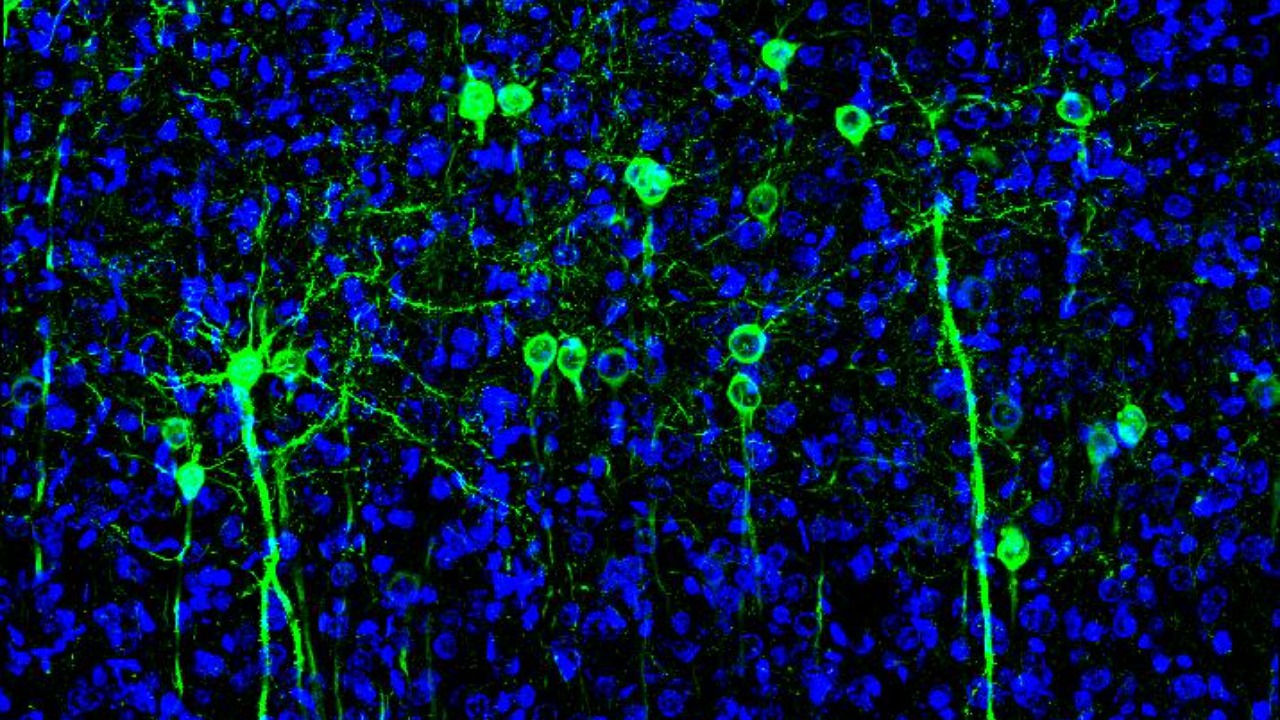

To move from intuition to proof, scientists needed a way to watch cold-sensing neurons in action without the noise of the rest of the nervous system. In work summarized under the heading Dec and Studying Cold, Sensing Nerves, teams used animal models that allowed them to isolate sensory neurons from skin and from internal organs and then cool each group in a controlled way. By tracking electrical activity in these cells, they could see which neurons fired first, how strongly they responded and how their patterns differed when the temperature dropped.

These experiments showed that the two populations of neurons are not just in different locations, they behave differently at the molecular level. The researchers reported that the cold sensors in the skin activated at relatively mild cooling, while those in deeper tissues required more intense cold to switch on, and they used genetic tools to identify the ion channels that were active in each type of neuron. According to the Dec report on how the body feels cold in two different ways, they relied on precise recordings of electrical activity in each type of neuron to uncover these differences, building a detailed map of how cold information enters the nervous system from the body’s surface and its interior.

Skin versus organs: a split system confirmed

The idea that the skin and internal organs might use different tools to detect cold has been around for years, but the latest work gives it concrete biological footing. A multidisciplinary team described in a Dec Study report set out to test whether the same molecular sensors operate in the skin and in organs such as the lungs and esophagus. They combined physiology, genetics and imaging to compare how nerves in these tissues respond when exposed to cold, and they found clear evidence that the body uses distinct sensor sets for external and internal cooling.

This group showed that the receptors in the skin are optimized for rapid detection of environmental changes, which helps an animal pull its hand away from an icy surface or seek shelter before hypothermia sets in. In contrast, the cold sensors in internal organs appear tuned to protect delicate tissues from damage by extreme inhaled air or swallowed liquids, and the Dec Study notes that this multidisciplinary approach demonstrated that the body uses different sensors to detect cold in the skin and in the internal organs, a division that may be especially important in species adapted to extreme thermal environments. By separating these roles, the nervous system can prioritize both quick behavioral responses and slower, protective reflexes inside the chest and abdomen.

How cool touch travels from skin to brain

Once cold receptors in the skin fire, their signals still have to travel a long way to shape conscious experience, and recent work has begun to trace that journey neuron by neuron. In a study highlighted under the label Jul and framed around the question What, How, researchers identified a specific pathway that carries cool touch information from the skin to the brain without triggering pain. They showed that certain spinal cord neurons relay gentle cooling signals to higher brain centers, forming a circuit that is distinct from the one that carries noxious cold, the kind that feels like burning or stabbing.

This separation matters because it explains how I can enjoy the feel of a cold glass against my palm while still recoiling from ice pressed too hard against my skin. The Jul report on how cool touch travels from skin to brain emphasizes that the newly discovered circuit specifically sends information about non-painful temperature changes and that it can be disrupted in ways that reduce cold pain without impairing normal sensation. That finding dovetails with the broader picture of specialized cold sensors, suggesting that the nervous system keeps pleasant coolness and dangerous cold on different channels from the very first step in the skin all the way to the cortex.

Cold in the lungs: why winter air can hurt to breathe

If skin cold is about comfort and frostbite, internal cold is about survival of sensitive tissues like the lungs. Reports from Dec on different sensors to detect cold in skin and lungs describe how nerves in the airways respond to inhaled cold air in ways that are distinct from the nerves in the skin. These airway sensors can trigger reflexes such as coughing, bronchoconstriction and changes in breathing pattern, all aimed at protecting the delicate surfaces where oxygen enters the blood from damage by extreme temperatures.

The Dec coverage of different sensors in the skin and lungs notes that researchers used sensor focused methods to show that the receptors in the respiratory tract are molecularly different from those in the skin, even though both respond to low temperatures. That distinction helps explain why a runner might feel a sharp, almost painful tightness in the chest on a freezing morning even when their hands feel only mildly cold. It also suggests that targeting lung specific cold sensors could be a way to ease symptoms in conditions like exercise induced bronchoconstriction or asthma without dulling the useful warning signals that come from cold skin.

Two cold sensors, many sensations

The most vivid illustration of this dual system comes from everyday experiences that most of us barely question. A research group described in a Dec report on scientists finding two different cold sensors in the body points out that the chill of a metal railing, the sting of cold air in the throat and the brain freeze from swallowing a very cold drink all arise from different combinations of surface and internal cold sensors. The same physical temperature can feel soothing on the skin yet brutal in the chest because the underlying receptors and circuits are tuned to different thresholds and risks.

According to that Dec account, this split system helps explain why cold air, cold drinks and cold surfaces create very different sensations, and it underscores that the body is not measuring temperature in a single, uniform way. Instead, the nervous system seems to ask context specific questions, such as whether a cold object might damage the skin, whether icy air could harm the lungs or whether a freezing liquid could threaten the esophagus and stomach. By assigning these jobs to different cold sensors, the body can generate a rich palette of sensations that guide behavior, from putting on gloves to slowing down sips of a milkshake.

The molecular thermometers behind cold sensing

Underneath these sensory differences lie proteins that act as the body’s molecular thermometers, converting changes in temperature into electrical signals that neurons can understand. Over the past two decades, researchers have identified various ion channels that open or close in response to specific temperature ranges, effectively turning thermal energy into electrical activity in the somatosensory system. A landmark review framed with the phrase Over the describes how these ion channels, many belonging to the TRP family, serve as the first step in peripheral thermosensation in mammals, including both warmth and cold.

One of the scientists at the center of this work, Ardem Patapoutian, has described these channels as the body’s molecular thermometers, and he and colleagues have shown that some of them respond not only to temperature but also to chemicals, including ingredients in garlic and wasabi. In a profile of David Julius and Ardem Patapoutian, the report notes that he calls these channels the body’s molecular thermometers and highlights how one ion channel can be activated by both heat and pungent compounds. The new cold sensor research builds on that foundation by showing that different combinations of these ion channels are expressed in skin versus internal organ neurons, helping to explain why the same drop in temperature can produce such different sensations depending on where it is felt.

From basic discovery to potential therapies

Understanding that the body runs two parallel cold sensing systems is not just a curiosity, it has practical implications for medicine. If specific ion channels and neural circuits are responsible for painful internal cold, for example in the lungs or esophagus, then drugs or devices that selectively dampen those pathways could ease symptoms without blunting the useful warning signals that come from the skin. The detailed mapping of cold sensitive neurons in Dec and Studying Cold, Sensing Nerves, which relied on precise recordings of electrical activity in each type of neuron, gives drug developers a clearer set of targets than the field had even a decade ago.

There are also implications for people who live or work in extreme environments, from Arctic construction crews to high altitude athletes. The Dec Study that demonstrated different sensors for cold in the skin and internal organs notes that this division may be especially important in species adapted to extreme thermal environments, suggesting that evolution has fine tuned these systems to balance performance and protection. As researchers continue to trace how cool touch travels from skin to brain and how internal cold sensors in the lungs and other organs feed into reflex circuits, I expect to see more focused strategies for managing cold related pain, respiratory distress and even some forms of chronic cough, all grounded in the simple but powerful insight that not all cold is created equal.

More from MorningOverview