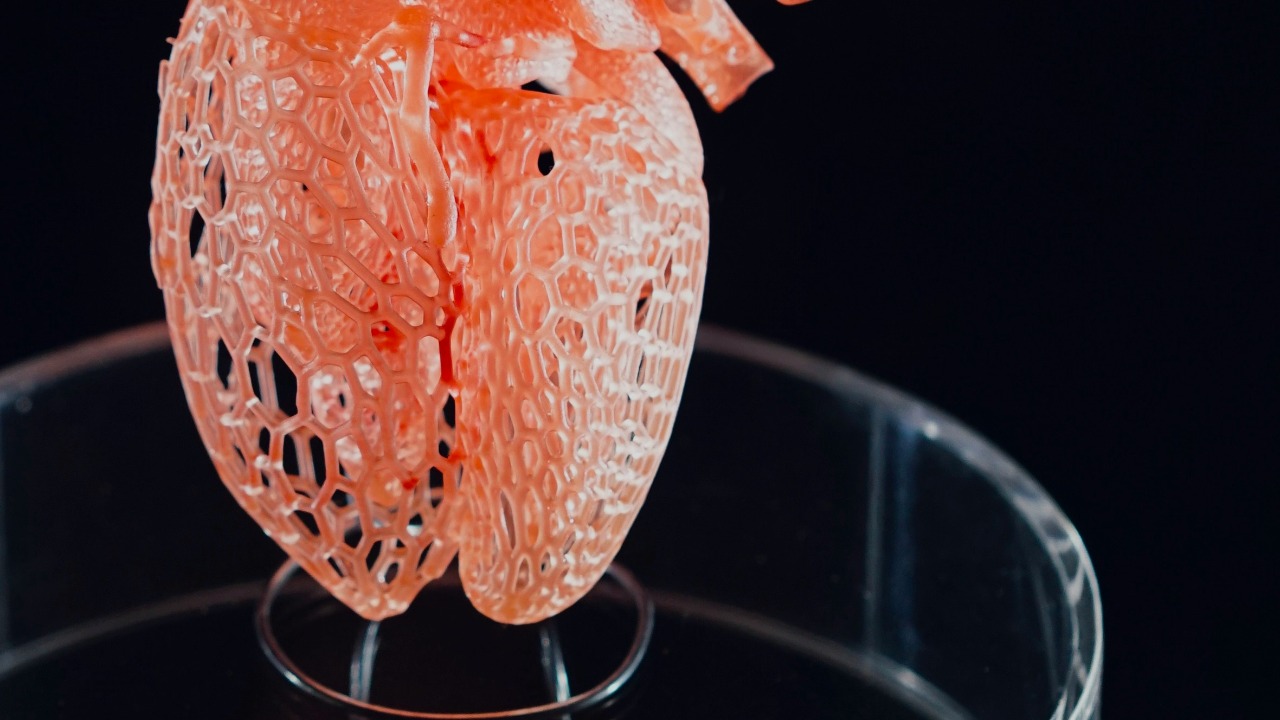

Researchers have unveiled a new 3D‑printable material that can be stretched, sutured, and implanted, edging artificial organs closer to routine clinical use. By combining the mechanical resilience of plastics with the biological friendliness of soft tissue, the material is designed to survive both the violence of surgery and the subtler stresses of life inside the body. It is not a fully functioning organ yet, but it directly targets some of the toughest engineering bottlenecks that have kept lab‑grown hearts, livers, and kidneys in the realm of promise rather than practice.

The material that can be printed, stretched, and stitched

The new material is built around a precursor mixture that can be shaped in a printer and then rapidly solidified, giving surgeons something they can actually handle. In the reported experiments, a researcher exposed this precursor to ultraviolet light for only a few seconds, which initiated polymerization and produced a robust, bottlebrush‑like network that behaves more like living tissue than brittle plastic. The result is a synthetic structure that can be cut, stretched, and even pierced with surgical needles without shattering, a critical step if 3D‑printed constructs are ever to be sewn into a beating heart or a moving lung.

What makes this advance stand out is its explicit focus on the realities of the operating room rather than just the elegance of the lab bench. The team behind the work showed that the printed material could be sutured and implanted in animal models, and the project has attracted support from the Virginia Innovation Partnership Corporation’s Commonwealth Commercialization fund, a sign that it is being positioned for translation rather than a one‑off demonstration. By pairing a fast UV‑triggered chemistry with a design that mimics the elasticity of soft organs, the developers of this 3D‑printing material are trying to close the gap between printable shapes and implantable parts.

Why organ engineers needed a new kind of “ink”

For all the hype around bioprinting, most existing “inks” have been compromises, either mechanically weak hydrogels that tear under stress or rigid polymers that cells struggle to colonize. Surgeons need constructs that can be clamped, tied, and manipulated, while biologists need scaffolds that allow cells to migrate, proliferate, and form functional tissue. The new bottlebrush‑based material is designed to sit in that middle ground, soft enough to deform with the body but tough enough to survive the rigors of implantation and early healing.

That balance matters because the field has already shown that 3D printing can work in principle when the material is right. In June, 3DBio Therapeutics printed and implanted an ear made from a patient’s own cells in a clinical trial, a landmark case that used cartilage, which is mechanically forgiving and relatively simple compared with a heart or kidney. The fact that 3DBio Therapeutics could run a regulated clinical trial at all shows how far the technology has come, but it also highlights how much harder it will be to print complex, load‑bearing organs without better structural materials. The new implantable polymer is an attempt to give future printers a more surgical‑grade “ink” than the gels that supported that early clinical trial.

Vessels, not volume, are the real bottleneck

Even with a tougher printable material, the hardest problem in artificial organs is not filling space, it is feeding cells. Every living organ is threaded with a dense, branching network of blood vessels that deliver oxygen and nutrients to every corner, and without that micro‑plumbing, printed tissue dies from the inside out. Lab‑grown organs have long been described as a “holy grail” of organ engineering precisely because recreating this vascular complexity has proved so difficult, even as printers have become more precise and bio‑inks more sophisticated.

Recent work has started to chip away at that barrier by showing that intricate vascular networks can be printed directly. Researchers have demonstrated 3D‑printed blood vessels that form complex, branching structures, bringing artificial organs closer to reality by allowing thicker tissues to survive and function. In one set of experiments, scientists produced vessel networks that could, in principle, be used for personalized medicine, where a patient’s own cells are seeded onto a pre‑printed scaffold that already contains channels for blood flow. These lab‑grown vessels do not yet match the full complexity of a human liver or kidney, but they show that the vascular problem is no longer intractable.

Complex blood vessel nets meet a tougher scaffold

The new material arrives just as other teams are learning how to print vessel networks that look more like the real thing. Earlier this year, researchers reported that complex blood vessel nets could be 3D printed with a hierarchy that mirrors the body’s own, from larger conduits down to smaller branches. These structures are designed to integrate with the body’s existing circulation, addressing one of the main reasons artificial organ transplants have been held back: the difficulty of connecting printed tissue to the host’s microvasculature without clotting or collapse.

When I look at the trajectory of the field, the synergy is obvious. A material that can be stretched and sutured without tearing is exactly what surgeons need to anchor these complex vascular nets inside a patient, while the printed vessels themselves provide the lifelines that keep the implanted cells alive. The latest research on complex blood vessel nets suggests that future constructs could be printed as integrated systems, with structural walls, perfusable channels, and cell‑friendly interiors all produced in a single build. The new bottlebrush‑style polymer is not the whole answer, but it is the kind of scaffold that could hold such a system together in the messy environment of a human body.

From windpipes to Teaching Tissues: proof that implants can work

One way to judge the significance of a new material is to look at what has already been possible with less advanced scaffolds. Earlier this year, a woman received a 3D‑printed windpipe in what was described as a world‑first procedure, a striking example of how far surgeons are willing to push the technology when the clinical need is urgent. Rather than the ink you might see in your printer at home, the team used a bio‑ink that carried living cells, creating a structure that was designed to integrate with her airway and, crucially, to last only five years before being replaced as her body changed.

Outside the operating room, companies are already using synthetic polymers to mimic organs for training and planning. A Texas biotech startup, SiMMo3D, has launched 3D‑printed organ models called Teaching Tissues that are produced using a synthetic polymer resin, a variety of colors, and multiple 3D printers. These Teaching Tissues are built from a combination of MRI data and CT scans, giving surgeons and students realistic models to cut, suture, and rehearse on before they ever touch a patient. The success of that approach shows that structurally robust, anatomically accurate prints are already valuable, and it underscores why a new implantable material that behaves more like living tissue could be transformative. The windpipe case, described with the phrase “Rather than the ink you might see in your printer at home,” and the commercial rollout of Using Teaching Tissues both hint at how quickly the line between model and implant is starting to blur.

Printing organs in microgravity

While most of the attention is on what can be printed in hospitals and university labs, some of the most ambitious work is happening in orbit. NASA has been testing 3D bioprinting on the International Space Station, using microgravity to assemble delicate tissues that would sag or collapse under their own weight on Earth. In microgravity, cells and soft gels can be layered without the same structural constraints, which allows researchers to explore architectures that might be impossible in a terrestrial lab but highly relevant once translated back to ground‑based manufacturing.

The agency has signaled that it is “Close to the future” of printing artificial organs in space, treating the ISS as a testbed for technologies that could eventually supply transplantable tissues for patients on Earth. The work on 3D bioprinting in orbit is not just a curiosity, it is a way to probe how cells behave when freed from gravity’s pull, and to refine printing strategies that might later be adapted to the new bottlebrush‑style materials now emerging. A separate report framed the effort with the phrase “Close to the future: NASA will print artificial organs in space,” underscoring how seriously the agency takes the idea that space‑based manufacturing could accelerate progress toward functional organs.

Hype, skepticism, and the long road to full organs

Every leap forward in bioprinting tends to trigger a wave of headlines about “printed hearts” and “on‑demand organs,” but the people closest to the work are usually more cautious. Engineers who follow the field closely have argued that companies like TeVido and Organovo are likely to build solid businesses printing tissues for research or grafts, but that producing a fully functional, living organ is a different challenge entirely. The gap between a patch of liver tissue for drug testing and a transplant‑ready liver that can regulate metabolism, detoxify blood, and respond to hormones is enormous, and no single material, however clever, will close it overnight.

From my vantage point, the new stretchable, suturable polymer should be seen as a tool that makes the next set of experiments possible, not as a magic bullet. It will help researchers print thicker constructs, withstand surgical handling, and perhaps support more complex vascular networks, but it does not solve issues like immune rejection, long‑term remodeling, or the need for nerves and lymphatics. The sober view expressed in analyses of whether 3D‑printed organs can live up to the hype, which note that a fully functional organ is “different,” remains accurate even as the technology improves. The latest material advances sit squarely within that context, giving companies such as Organovo and TeVido better options but not a shortcut to whole‑organ replacement.

Regenerative medicine’s 2025 momentum

What is striking about the current moment is how many pieces of the puzzle are moving at once. Regenerative medicine has seen a steady stream of innovations in 3D printing through 2025, with new printers, bio‑inks, and hybrid materials all being tested in parallel. Reports from the field describe how 3D printing technology continues to drive innovation in regenerative medicine, offering alternative strategies for tissue repair and replacement that complement, rather than immediately replace, traditional transplantation.

Within that broader wave, the new bottlebrush‑style material is part of a pattern in which researchers are trying to make printed constructs more mechanically realistic and clinically usable. Significant advancements in 3D printing have persisted across multiple fronts, from better control of cell placement to smarter scaffolds that degrade at controlled rates as native tissue grows in. The latest survey of innovations in 3D printing highlights how these incremental gains are starting to add up, creating an ecosystem in which a new material can be quickly tested with existing printers, cell types, and surgical models.

How close are we, really, to printed organs on demand?

When I weigh the evidence, I see a field that is undeniably closer to functional artificial organs than it was even a few years ago, but still far from the science‑fiction vision of on‑demand hearts and kidneys. The new material that can be printed, stretched, and implanted addresses a very real bottleneck: the need for scaffolds that behave like tissue in the surgeon’s hands. Combined with advances in vascular printing, clinical trials like the 3DBio Therapeutics ear, and high‑profile cases such as the 3D‑printed windpipe, it suggests that more partial organs and hybrid implants will reach patients in the near term.

At the same time, the most ambitious visions, including NASA’s work to print organs in microgravity and the push to recreate entire organ systems with nerves, vessels, and immune compatibility, remain long‑term projects. The phrase “Close to the future” captures the mood well: the future is visible, but not yet here. For now, the new 3D‑printable material should be understood as a crucial step in a long relay, handing off a more capable scaffold to the next generation of biologists, surgeons, and engineers who will try to coax it into behaving like a living organ. As those teams iterate, the combination of better materials, smarter printing strategies, and rigorous clinical testing will determine how quickly the promise of artificial organs moves from the lab to the ward.

More from MorningOverview