Scientists are increasingly blunt about a climate-driven shift that could upend daily life for millions of people: extreme heat, destabilized water supplies, and violent storms are converging into a new kind of risk. The phenomenon is not a single storm or season, but a rapidly emerging pattern in which once-rare events become regular features of the forecast. As global warming accelerates, researchers warn that the consequences for health, infrastructure, and basic habitability will be profound unless emissions fall sharply and communities adapt fast.

From atmospheric rivers unloading record rain on the West Coast to melting glaciers and mounting heat that could push entire regions beyond what humans can safely endure, the warning signs are already visible. I see a throughline in the latest research: the physical limits of the planet, and of the human body, are being tested in real time, and the window to avoid a far more dangerous “new reality” is closing quickly.

What scientists mean by a “new reality”

When researchers talk about a looming “new reality,” they are describing a world where climate extremes are no longer outliers but the baseline. A growing body of work on the Global Tipping Points suggests that Earth systems are edging toward thresholds that, once crossed, could lock in rapid and potentially irreversible changes. In that framing, humanity itself becomes “the human experiment,” living through conditions no modern society has ever had to navigate, with no guarantee that our current ways of organizing economies and cities will still function.

Scientists are not just warning about more bad weather, they are mapping how cascading impacts could reshape where people can live, how food is grown, and which regions remain stable enough to support complex societies. In one assessment, Scientists describe a powerful phenomenon that could “usher in” this new era, tying together rising temperatures, shifting ocean currents, and destabilized ice sheets. The message is that the climate system is not changing in a slow, linear way; it is lurching toward states that could feel radically different within a single generation.

Atmospheric rivers: the sky’s firehose gets stronger

One of the clearest examples of this emerging pattern is the rise of extreme atmospheric rivers, the long, narrow bands of moisture that act like skyborne firehoses. These systems, which can stretch for thousands of miles, are already a familiar feature along the Pacific coast, but as the planet warms, Atmospheric rivers are expected to be bigger and more hazardous on average because warmer air and oceans allow the atmosphere to hold more moisture. That extra water vapor translates directly into heavier downpours when these plumes make landfall, raising the odds of catastrophic flooding.

Physically, these rivers in the sky are Formed by winds associated with cyclones and typically range from 250 miles to 375 miles (400 to 600 k) wide, which means they can blanket entire states with intense rain or snow. When such a system stalls or arrives in quick succession, the result can be days of relentless precipitation that overwhelm rivers, storm drains, and hillsides. In a warming climate, the concern is not just that these events will be more frequent, but that each one will carry more water, turning what used to be seasonal nuisances into life-threatening disasters.

California’s holiday storms show what is coming

The latest storms in California offer a preview of how this new pattern plays out on the ground. A recent round of torrential rain moving into Southern California raised a Level 3 of 4 flooding rain risk for more than 15 million people, including communities that had already been soaked earlier in the week. Forecasters warned that the storm would deliver several inches of rain in a short window, on top of saturated soils, creating ideal conditions for flash floods and mudslides. For residents, that meant holiday travel plans colliding with evacuation alerts and road closures, a collision of climate risk and everyday life that is becoming more common.

At the same time, a broader holiday forecast warned that Flooding rain and snow are expected to impact California this week, with a second powerful atmospheric river bearing down on the state and the San Francisco Bay Area. That one-two punch of storms illustrates how back-to-back systems can leave little time for rivers to recede or for emergency crews to clear debris. When the atmosphere is primed with extra moisture, the odds of such sequences rise, turning what might once have been a single bad storm into a prolonged siege.

Burn scars, flood watches, and millions at risk

Layered on top of these wetter storms is another emerging hazard: the interaction between wildfire burn scars and heavy rain. In and around Los Angeles, Millions of people have been placed under flood watches as storms target hillsides stripped of vegetation by recent fires, including areas like Pasadena, Calif. Without roots to hold soil in place, intense rainfall can transform charred slopes into rivers of mud and debris that barrel into neighborhoods with little warning. Evacuation orders in these zones are not hypothetical drills; they are life-or-death directives shaped by the new overlap of fire and flood seasons.

Forecasts have also highlighted how a Strong atmospheric river could deliver up to 500 mm of rain to parts of California over just a few days, a staggering amount of water for any landscape to absorb. When that kind of deluge hits burn scars, the risk of debris flows and sudden flooding spikes dramatically. I see this as a textbook example of compound risk: climate change is not only intensifying storms, it is also lengthening and worsening wildfire seasons, and the two trends together create threats that are far greater than the sum of their parts.

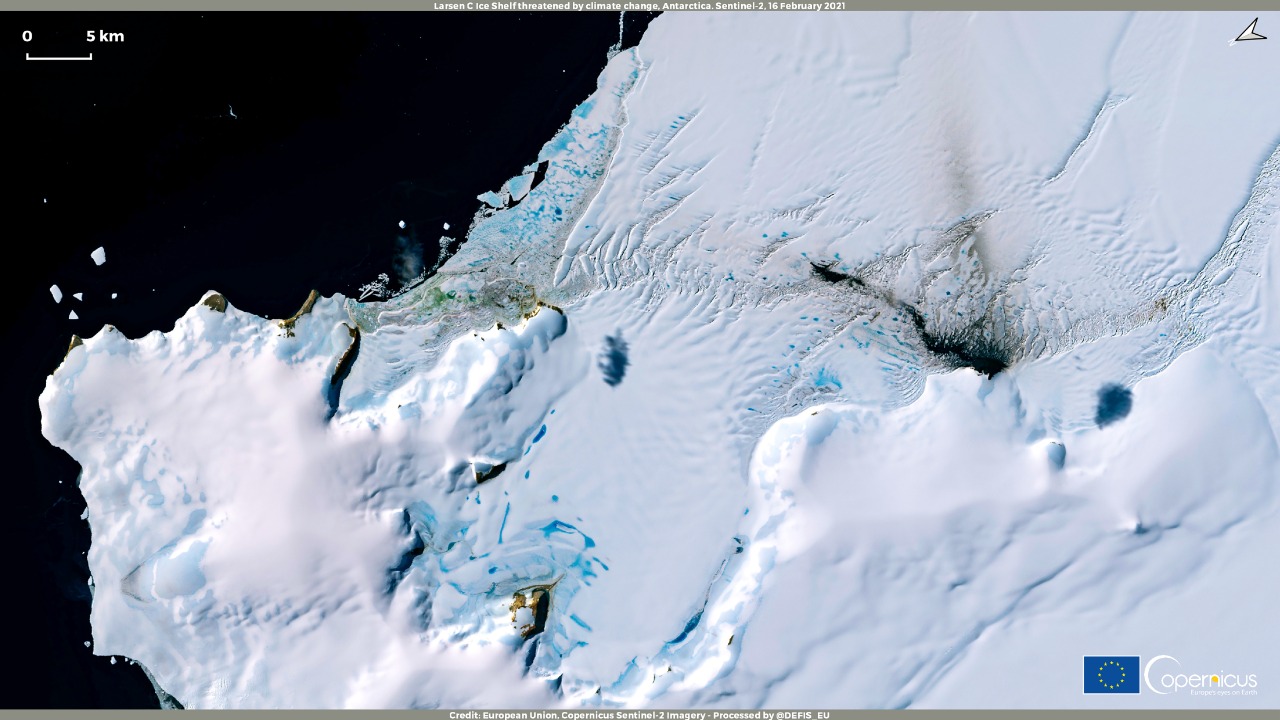

Melting glaciers and a planet edging toward 2 degrees

Far from the Pacific coast, another slow-motion phenomenon is setting up serious trouble for water supplies and weather patterns. As glaciers retreat, melting ice is reshaping river flows that billions of people rely on for drinking water, irrigation, and hydropower. Initially, increased melt can boost river levels, but over time, as ice reserves shrink, downstream communities face the risk of severe shortages. The same process adds fresh water to oceans, which can disrupt currents and, according to researchers, even worsen hurricanes and tornadoes by altering temperature gradients and atmospheric dynamics.

Scientists are especially alarmed because the world is now pushing toward 2 degrees Fahrenheit above preindustrial levels, a threshold that many studies have flagged as a tipping point for more extreme impacts. In one analysis, Scientists warn that this warming will affect millions of people by destabilizing glaciers that have acted as frozen reservoirs for centuries. The consequences they describe are “staggering,” not only for mountain communities but for lowland cities and farms that depend on predictable meltwater to get through dry seasons.

Heat that could make regions uninhabitable

While storms and melting ice grab headlines, another, quieter threat is building: extreme heat that pushes the human body beyond its limits. A recent assessment warns that Scientists see a “dangerous threat” that could affect 2 billion people if certain changes are not made, with More than one in five people worldwide potentially exposed to conditions that strain the body’s ability to cool itself. These are not just uncomfortable heat waves; they are combinations of temperature and humidity that can become lethal in a matter of hours for those without access to cooling or shade.

Researchers highlighted a pivotal study, cited by the Institute of Science in Society and Environmental Professionals (ISEP), which examined the limits at which humans can live and function. They noted that at certain thresholds of heat and humidity, outdoor labor becomes impossible and even resting in the shade can be deadly, effectively rendering some regions uninhabitable because of life-threatening heat. For cities already grappling with urban heat islands, this research is a stark warning that adaptation will require more than a few extra cooling centers; it may demand rethinking work schedules, building design, and even long-term population distribution.

Global warming from fossil fuels and the biggest risks of our time

All of these phenomena trace back to a common driver: the steady accumulation of greenhouse gases from burning coal, oil, and gas. Analysts tracking the Biggest Environmental Problems of our lifetime place Global Warming From Fossil Fuels at the top of the list, noting that After several consecutive months of record-breaking temperatures, the planet is now in uncharted territory. The basic physics are straightforward: more carbon dioxide and methane in the atmosphere trap more heat, which in turn supercharges storms, dries out forests, melts ice, and raises sea levels.

That warming is already manifesting in ways that touch nearly every aspect of modern life, from food prices to insurance premiums. A separate warning from Scientists described “clear, profound … consequences” over the next eight years if emissions are not rapidly reduced, underscoring that the window for relatively smooth adaptation is closing. I read these assessments as a call to treat climate risk not as a distant environmental issue but as a central factor in economic planning, public health, and national security.

Ocean currents, tipping points, and a climate system on edge

Beyond heat and storms, researchers are increasingly focused on the stability of the oceans, which absorb most of the excess heat from global warming and drive weather patterns worldwide. One of the most concerning possibilities is a disruption of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, the powerful ocean current that helps regulate temperatures in Europe, North America, and parts of Africa. A new study cited by Scientists indicates that a collapse of this circulation can no longer be considered an unlikely scenario, a finding one researcher called “quite a shocking” development.

If that current were to weaken sharply or shut down, the ripple effects could be enormous, including shifts in monsoon patterns, more extreme winters in some regions, and accelerated sea level rise along certain coastlines. This is where the idea of tipping points becomes more than an academic concept: once such a system crosses a threshold, it may not return to its previous state even if emissions fall. Combined with the risks flagged in the What’s happening analysis, where Hansen and a team of international scientists emphasize that “the main issue is the rate of sea level rise,” it becomes clear that ocean dynamics are central to the new climate reality scientists are warning about.

From mountain ranges to global systems: what comes next

Zooming out, the pattern that emerges from mountain glaciers, ocean currents, and atmospheric rivers is one of interconnected stress. In December, the U.N. Environment Programme released the seventh edition of its Global Environment report, highlighting how mountain ranges are warming faster than the global average, with cascading effects on water, ecosystems, and downstream communities. Those changes feed into broader climate, health, and environmental costs that are already straining budgets and institutions.

At the same time, climate researchers are tracking how these shifts could nudge the planet toward the next ice age over very long timescales, even as near-term warming dominates the headlines. A recent synthesis, shared as Scientists sounded the alarm, framed today’s rapid warming as a sharp deviation from the slow, natural cycles that have governed Earth’s climate for millennia. In that context, the “new phenomenon” that could hit millions is not a single storm or current, but the speed and scale of human-driven change, which is now outpacing the ability of many natural and social systems to keep up.

More from MorningOverview