Interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS has turned a routine solar system flyby into a natural physics experiment, with a wobbling jet and a tail that appears to point toward the Sun instead of away from it. As the object races through our neighborhood on a one-time visit from deep space, its quivering structures are giving astronomers a rare look at how an alien comet spins, sheds material, and reacts to solar radiation.

By tracking the strange anti-tail and the rhythmic motion of its jets, researchers are beginning to piece together the internal structure and rotation of 3I/ATLAS, as well as how it compares with the only two other confirmed interstellar visitors. I see this comet as both a messenger from another planetary system and a stress test for our theories about how small icy bodies behave when they are suddenly thrust into the glare of the Sun.

3I/ATLAS joins a tiny club of interstellar visitors

Before anyone saw its wobbling jets, 3I/ATLAS was already remarkable simply for existing. According to official Facts and FAQS, Comet 3I/ATLAS is only the third known object to pass through our solar system from interstellar space, following 1I/ʻOumuamua and 2I/Borisov. That status alone makes every detail of its behavior precious, because each interstellar Comet samples a different planetary nursery and a different history of heating, collisions, and chemical processing.

Unlike long period comets that loop back after millions of years, 3I/ATLAS is on a hyperbolic path that will carry it away forever once it leaves the Sun’s grip. The official Stats show that its trajectory and speed cannot be explained by an origin in the distant Oort Cloud, which is why it carries the “I” designation that marks it as Interstellar. I see that label not as a curiosity in a catalog, but as a reminder that this object formed around another star and that its dust and ice preserve conditions that our own solar system never experienced.

A close, fast flyby through the inner solar system

The current apparition of 3I/ATLAS is a fleeting opportunity, and astronomers have scrambled to use every available telescope while the comet is bright enough to study. Live coverage of its path has emphasized that the Interstellar visitor is making its closest approach to Earth in Dec, with observers tracking how ATLAS brightens and fades as it sweeps past the Sun. In practical terms, that means a narrow window in which the jets and tail can be resolved well enough to measure their motion rather than just their overall glow.

Reports on the comet’s trajectory note that Astronomers have pinned down the timing of its closest pass with impressive precision, down to the minute in Dec, which helps coordinate observations across observatories on multiple continents. One detailed live update on Interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS describes how the object’s changing distance and phase angle affect the apparent length and orientation of its tail. I find that choreography between orbital mechanics and observational strategy crucial, because the wobbling jet and sunward tail are only visible at all thanks to this precise alignment of geometry, timing, and instrumentation.

Gemini North and the first detailed portraits of an alien comet

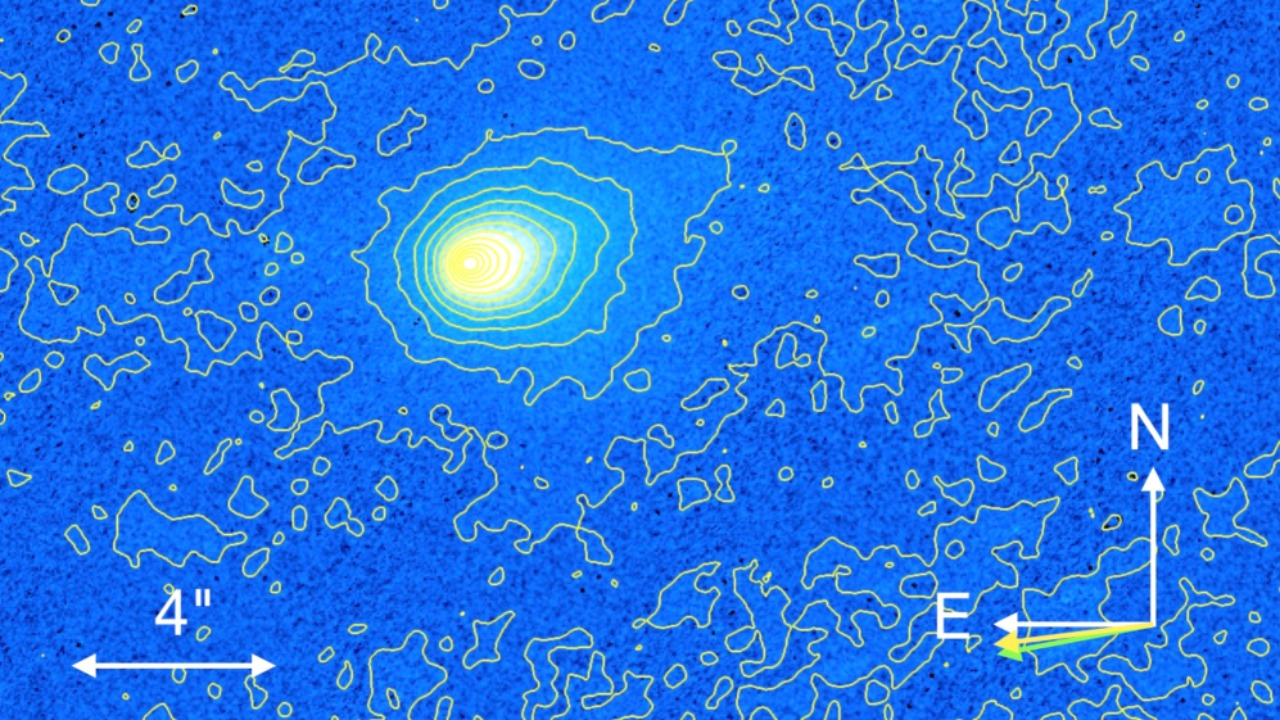

To understand what is wobbling, researchers first needed sharp images of the comet’s inner coma and nucleus region. One key milestone came when 3I/ATLAS was photographed in color by the Gemini North telescope on 26 November 2025, capturing the structure of its dust and gas in unprecedented detail for such a distant and fast moving target. Those images, documented in the technical summary for 3I/ATLAS, showed the comet at an apparent magnitude of 14.2, faint by backyard standards but bright enough for a large observatory to dissect its features.

From my perspective, the Gemini North data did two important things. First, it confirmed that ATLAS has a well developed coma and tail, more reminiscent of 2I/Borisov than of the oddly bare 1I/ʻOumuamua, which never grew a visible tail at all. Second, the color and morphology hinted at active jets near the nucleus, setting the stage for later, more time resolved observations that would reveal the periodic wobble. Without that early, high resolution look, the later reports of a quivering anti-tail might have been dismissed as artifacts of poor seeing or instrumental noise rather than real structures tied to the comet’s rotation.

The TTT telescope’s discovery of a wobbling jet

The real breakthrough came when a smaller but nimble facility, The TTT telescope at the Teide Observatory, began monitoring 3I/ATLAS night after night. According to a detailed release, The TTT telescope at the Teide Observatory detects the first periodic and wobbling jet in an interstellar comet, using a series of images that track how a narrow feature in the coma shifts position over time. That finding is remarkable because it turns a static snapshot into a movie of the comet’s activity, revealing not just that material is streaming out, but that the direction of that stream is changing in a regular pattern.

In that report, the team describes how the wobble likely reflects the rotation of the nucleus, with the jet anchored to a specific active region on the surface that sweeps around like a lighthouse beam. The Teide Observatory analysis emphasizes that this is the first time such a periodic and wobbling jet has been documented in an object formed outside our Solar System, which is why the The TTT result has drawn so much attention. I see this as a crucial bridge between the static portraits from large telescopes and the dynamic behavior that tells us how the comet spins and vents material.

A quivering anti-tail that points toward the Sun

Alongside the wobbling jet, 3I/ATLAS has displayed a feature that looks almost like a comet tail in reverse. Scientists have spotted a rare and puzzling behaviour in interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS as it approached the Sun, in which a bright, narrow structure appears to extend sunward rather than away from the star. In detailed video analysis, researchers describe this as an anti-tail, a perspective effect that occurs when the observer’s line of sight lies close to the comet’s orbital plane, causing dust that trails along the orbit to appear as a spike pointing toward the Sun instead of a conventional tail pointing away.

What makes this anti-tail so compelling is that it is not static. The same Dec observing campaign reports that the comet’s unusual anti-tail was seen quivering every 7.75 hours, a rhythm that matches the inferred rotation period of the nucleus. In other words, the anti-tail is not just a geometric illusion, it is being modulated by the same wobbling jets that feed dust into the comet’s orbital wake. I find that interplay between geometry and physics striking, because it means the sunward pointing feature is effectively a seismograph for the comet’s spin, recording each turn of the nucleus as a subtle twitch in the anti-tail.

Linking the 7.75 hour wobble to the comet’s rotation

To move from pretty pictures to physical insight, astronomers have focused on the precise timing of the quiver. In their analysis of interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS as it approached the Sun, they report that the anti-tail’s brightness and orientation repeat every 7.75 hours, a period that is too regular to be explained by changing viewing geometry alone. That figure, 7.75, is now the leading candidate for the comet’s rotation period, tying the observed wobble directly to the spin of the nucleus and the location of active jets near its surface.

One detailed breakdown of the imaging sequence notes that the motion is linked to the rotation of the nucleus and active jets near its surface, with each rotation bringing the jet into a slightly different orientation relative to the Sun and Earth. In that view, the anti-tail becomes a kind of rotating sprinkler pattern, where the dust stream is periodically refreshed and redirected as the jet sweeps around. I see this as a powerful example of how time series imaging can turn a distant point of light into a three dimensional object with a measurable day length, even when the nucleus itself is far too small to resolve directly.

What the wobbling jets reveal about 3I/ATLAS’s interior

Once the rotation period is known, the next question is what it says about the comet’s internal structure. A 7.75 hour spin is relatively brisk but not extreme for a small icy body, which suggests that 3I/ATLAS has enough internal cohesion to avoid flying apart under centrifugal forces. The presence of a stable, periodic jet implies that at least one region on the surface is both structurally robust and rich in volatile material, capable of sustaining continuous outgassing as it cycles in and out of sunlight.

From my perspective, the wobble also hints at whether the comet is in simple rotation or in a more complex, tumbling state. If the jet’s direction changes in a smooth, sinusoidal pattern, that would favor a single spin axis, while more erratic shifts could point to a nucleus that is precessing or wobbling like a poorly balanced top. The Dec observing reports, which emphasize a regular pattern tied to the nucleus and active jets near its surface, lean toward a relatively stable rotation. That stability, combined with the comet’s interstellar origin documented in the official Comet 3I/ATLAS Stats, suggests that the object has survived eons of interstellar travel without being shattered or spun into chaos by close encounters.

Comparisons with 1I/ʻOumuamua and 2I/Borisov

To appreciate how unusual 3I/ATLAS is, it helps to set it alongside its two predecessors. The first interstellar visitor, 1I/ʻOumuamua, showed no obvious coma or tail, and its odd acceleration sparked debates about whether it was a fragment of a planet, a fluffy dust aggregate, or something even stranger. The second, 2I/Borisov, looked more like a conventional comet, with a clear gas and dust tail but no reported periodic wobbling jet or anti-tail that pointed toward the Sun. In that context, 3I/ATLAS combines elements of both, with a robust coma and tail like Borisov but with dynamical behavior that is far more intricate.

What stands out to me is that each interstellar Comet has revealed a different facet of how small bodies can form and evolve around other stars. The detailed imaging by facilities like Gemini North and The TTT telescope at the Teide Observatory shows that ATLAS is not just a clone of any known solar system comet, but a distinct object with its own spin state, jet pattern, and dust distribution. The fact that Astronomers can now talk about a 7.75 hour rotation period, a wobbling jet, and a quivering anti-tail for an object that will never return underscores how quickly the field is learning to extract maximum information from brief, one time encounters.

Why the sunward tail and wobbling jets matter for comet science

Beyond the spectacle, the behavior of 3I/ATLAS has concrete implications for how scientists model comet activity. The anti-tail that appears to point toward the Sun forces researchers to account for the three dimensional distribution of dust along the comet’s orbit, not just the immediate push of solar radiation away from the star. By tying the quiver of that feature to the 7.75 hour rotation period, observers can test how different jet geometries and grain sizes reproduce the observed pattern, refining models that will apply to both interstellar and homegrown comets.

The wobbling jet itself is a rare laboratory for studying how localized activity shapes a comet’s evolution over time. If a single active region dominates the outgassing, it can gradually torque the nucleus, altering its spin rate and axis in a feedback loop that may eventually expose new areas or shut down old ones. The Dec reports that link the motion to the rotation of the nucleus and active jets near its surface suggest that 3I/ATLAS is in the early stages of that process, with a stable but potentially evolving spin state. I see this as a reminder that even a brief visit through the inner solar system can leave lasting fingerprints on an interstellar traveler, subtly reshaping it before it disappears back into the dark between the stars.

What comes next for observing 3I/ATLAS

As 3I/ATLAS recedes from the Sun, its coma will fade and its jets will weaken, but the data already collected will keep astronomers busy for years. High cadence imaging from facilities like The TTT telescope at the Teide Observatory and deep exposures from Gemini North will be combined with spectroscopic measurements to map the comet’s composition, dust grain properties, and gas production rates. The goal is to connect the observed wobbling jet and anti-tail to specific ices and minerals, building a chemical profile that can be compared with comets that formed around the Sun.

Future interstellar visitors will benefit directly from the playbook written for ATLAS. Observers now know to look not just for a tail, but for subtle, periodic motions in the inner coma that can reveal rotation periods and jet structures even when the nucleus itself is unresolved. The experience gained from tracking the quivering anti-tail of interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS as it approached the Sun in Dec will shape how Astronomers design campaigns for the next object that wanders in from another star. I expect that when that happens, the lessons from this wobbling, sunward tailed traveler will be front and center in every observing proposal.

More from MorningOverview