Far beneath the South Pacific, a continent the size of India has finally stepped out of the cartographic shadows. After centuries of speculation and decades of targeted surveys, scientists have now produced the first complete map of Zealandia, Earth’s largely submerged “eighth continent,” revealing its true scale, structure, and role in the planet’s deep history. What was once a geological rumor is now charted territory, with implications that stretch from plate tectonics to climate science and even national identity.

Most of this hidden landmass lies under thousands of meters of water, with only the peaks of its highest ranges emerging as New Zealand, New Caledonia, and a scattering of smaller islands. Yet the new mapping work shows that Zealandia is a coherent continent in its own right, not just a collection of isolated fragments, and that it has been shaping Earth’s surface for hundreds of millions of years.

How a “lost” continent hid in plain sight

For generations, school atlases taught that there were seven continents, full stop. The idea that an eighth, almost entirely underwater, could be lurking beneath the Pacific sounded more like science fiction than settled geology. In reality, the landmass now known as Zealandia has been part of scientific conversations for decades, but only recently has the weight of evidence pushed it firmly into the continental club. Researchers now describe Zealandia as a vast, coherent block of continental crust that simply happens to be mostly drowned.

Geologists classify continents not by whether they are dry land but by the thickness, composition, and elevation of their crust. By those measures, Zealandia fits the bill: it is made of buoyant, silica-rich rocks, it is significantly thicker than the surrounding oceanic crust, and it forms a distinct plateau that rises above the abyssal plains of the South Pacific. Earlier work had already suggested that this region, also called Te Riu-a-Māui in Māori and sometimes linked with the Tasman region as Zealandia, Te Riu and Tasm, was once part of a larger landmass, but only the latest mapping has stitched those clues into a full continental portrait.

From Gondwana to the South Pacific: a tectonic origin story

To understand why Zealandia is mostly underwater, I have to go back to the breakup of the ancient supercontinent Gondwana. Around 100 m years ago, Antarctica, Australia and Zealandia were all welded together as part of that giant landmass, sharing mountain belts, sedimentary basins, and a common tectonic fate. As the supercontinent began to fragment, rifts opened and new ocean crust formed, prying Zealandia away from its neighbors and setting it adrift into what is now the South Pacific.

One scientist, Dickens, has described how, if you go back about that 100 m year timescale, Antarctica, Australia and Zealandia were all one continent before rifting pulled them apart, a reminder that today’s map is just a snapshot in a long tectonic film. As Zealandia thinned and stretched during its separation from Gondwana, its crust lost buoyancy and gradually subsided, leaving only its highest ridges above sea level. Those surviving peaks now form the islands of New Zealand and New Caledonia, while the rest of the continent lies submerged but structurally intact beneath the surrounding ocean, a story that detailed reconstructions of Antarctica, Australia and Zealandia, Dickens help to anchor in deep time.

What makes Zealandia a continent, not just a microplate

Labeling Zealandia as a continent is not a branding exercise, it is a technical judgment based on measurable criteria. Continents are typically defined by their thick, buoyant crust, their geological diversity, and their clear separation from surrounding oceanic basins. Zealandia checks those boxes: it spans nearly two million square miles, larger than India and almost two-thirds the size of Australia, and it is built from granites, metamorphic rocks, and sedimentary sequences that match what geologists expect from continental crust rather than ocean floor.

Earlier debates framed Zealandia as a collection of microcontinents or fragments, but the new mapping shows that these pieces are stitched together into a single, coherent entity. The landmass includes New Zealand, New Caledonia and several smaller islands that sit atop a broad plateau of continental rock, rather than isolated volcanic hotspots. One detailed analysis notes that this submerged continent is at nearly two million square miles, larger than India and almost two-thirds the size of Australia, a scale that supports its status as a full-fledged continent and not a geological footnote, as highlighted in assessments that describe it as larger than India and almost two-thirds the size of Australia.

“Buried for 375 Years”: from cartographic rumor to mapped reality

The idea of a southern landmass in this region is not new. European mapmakers speculated about a great southern continent for centuries, and early explorers glimpsed pieces of what we now know as Zealandia without recognizing the full picture. Modern reporting has framed this long delay starkly, describing Zealandia as having been “buried for 375 Years” before finally being identified beneath the Pacific Ocean. That figure captures how long it has taken for scattered observations, from ship soundings to seismic lines, to coalesce into a coherent continental map.

Today, scientists describe Zealandia as Earth’s long-lost 8th continent, finally recognized beneath the Pacific and including New Zealand, New Caledonia and several smaller islands that rise from its submerged plateau. The phrase “Buried for 375 Years” is not just rhetorical flourish, it reflects the gap between early hints of a southern land and the modern synthesis that confirms a continent-scale structure, a narrative crystallized in accounts that describe how, after 375 years of obscurity, Buried for, Years, Zealandia, Earth, Long has finally been identified beneath the Pacific Ocean.

The world’s first fully mapped continent

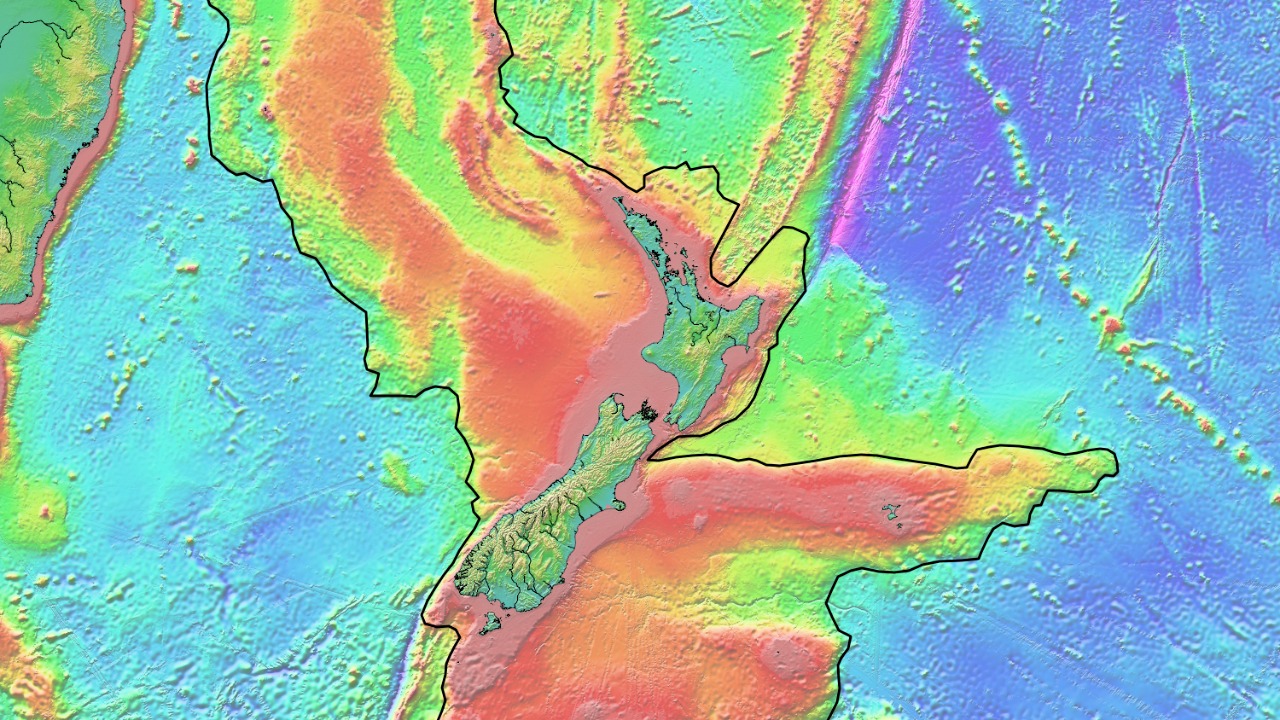

The breakthrough that has pushed Zealandia into the spotlight is not just its reclassification, but the fact that it is now the first continent to be completely mapped in modern detail. Researchers at GNS Science and partner institutions have assembled a high-resolution picture of its bathymetry, geology, and tectonic fabric, combining shipborne sonar, satellite data, and decades of fieldwork on the few islands that break the surface. That synthesis has turned what was once a patchwork of local studies into a continent-wide framework.

One project summary notes that Zealandia just became the first continent to be completely mapped, describing it as a world first in undersea mapping and emphasizing how the new dataset is already driving fresh discoveries about the continent’s structure and evolution. The work, led from New Zealand, has effectively “put Zealandia on the map,” as one researcher put it, and it underscores how advances in marine geophysics can rewrite even the most basic facts about Earth’s geography, a point underscored in the announcement that Zealandia just became the first continent to be completely mapped.

Inside the new Zealandia maps: ridges, basins and plate boundaries

What the new maps reveal is a continent that is anything but featureless. Zealandia is carved by deep basins, flanked by steep continental slopes, and crossed by fault systems that record its tortured tectonic past. The maps show how the continent’s crust thinned as it rifted from Gondwana, how volcanic arcs stitched across its margins, and how later plate motions warped and fractured its interior. For geologists, this is a rare chance to see a continent that has been stretched and submerged without being completely destroyed.

Detailed visualizations released by GNS Science, along with an interactive platform called E Tūhura – Explore Zealandia, allow users to zoom in on these structures, tracing the continent’s mountain belts, sedimentary basins, and plate boundaries in unprecedented detail. The new imagery does not just outline the edges of Zealandia, it illuminates the continent’s tectonic origins and ongoing seismic hazards, as described in coverage that notes how new maps released by But, GNS, Science, Explore Zealandia allow the public to see the lost continent as never before.

Interactive cartography: bringing a drowned continent to the surface

One of the most striking aspects of the Zealandia project is how quickly its findings have been translated into public tools. Rather than confining the new maps to specialist journals, the research teams have built interactive platforms that let anyone explore the continent’s underwater topography from a laptop or phone. These tools turn abstract bathymetric grids into intuitive 3D landscapes, making it easier to grasp how a continent can exist almost entirely below sea level.

Users can now pan across Zealandia’s submerged plateaus, zoom into its fault-bounded basins, and follow the line of its plate boundaries in a way that was impossible even a few years ago. One report invites readers to take a look at the new interactive Zealandia map at GNS Science’s website, underscoring how digital cartography is collapsing the distance between frontier research and public understanding, and how anyone can now Take, Zealandia, GNS, Science for a virtual spin.

Zealandia in the popular imagination: from Instagram reels to viral headlines

Scientific recognition is only part of the story; Zealandia has also captured the public imagination. Social media posts now frame the discovery in playful terms, with one viral reel urging viewers to “wake up” because a new continent has just dropped. That same clip notes that scientists confirm the location of this hidden landmass and that only about five percent of it rises above the ocean’s surface, a statistic that neatly explains why it took so long to recognize its true nature.

The idea that there might be eight continents, not seven, has become a kind of plot twist in online discussions, with creators like mailo TALKS A CONTINENT and soukaynahmaili using short videos to explain how Zealandia fits into Earth’s geography. One such reel spells out that scientists confirm the location of this submerged continent and that only about five percent of it is above water, turning a dense geological argument into a shareable narrative about how Scientists confirm, TALKS, CONTINENT, Plot, There might be eight continents after all.

Why mapping Zealandia matters for science and society

Beyond the novelty of adding an eighth continent to the schoolroom list, mapping Zealandia has concrete scientific payoffs. The continent’s rocks record how Earth’s crust responds when it is stretched to the breaking point, offering a natural laboratory for understanding rifting, subsidence, and the birth of new ocean basins. Its sedimentary basins preserve archives of past climates and ocean conditions, which can help refine models of how the planet’s systems respond to long-term shifts in carbon dioxide, sea level, and temperature.

There are also practical stakes. Better maps of Zealandia’s structure improve assessments of earthquake and tsunami hazards around New Zealand and neighboring islands, since many active faults and plate boundaries run along the edges of the submerged continent. The new data will inform resource exploration, from hydrocarbons to critical minerals, and sharpen debates over maritime boundaries and economic zones. As one detailed feature on the continent’s mapping notes, researchers like Mortimer at GNS Science in New Zealand see the project as a way to understand how Earth’s surface has evolved over some 300 million years, a perspective that underscores why Jan, Zealandia, Mortimer, New Zealand, GNS, Science view the continent as a key piece of the global tectonic puzzle.

Rewriting the mental map of Earth

Zealandia’s emergence as a fully mapped continent forces a quiet but profound revision of how I picture the planet. The familiar outlines of the world’s landmasses are, it turns out, only part of the story, with a continent-sized block of crust hiding beneath the South Pacific that is larger than India and almost two-thirds the size of Australia. That realization underscores how much of Earth’s architecture remains concealed beneath the oceans, and how our mental maps are biased toward what happens to be above sea level at this particular moment in geological time.

Popular explainers now describe Zealandia as a vast, mostly submerged landmass in the South Pacific that has played a major role in shaping Earth’s surface over deep time, while more technical features trace how, as Zealandia began to break away from Gondwana, its crust thinned and subsided into the ocean. Together, these accounts show that the continent is not an oddity but a missing chapter in the story of how Earth’s surface has evolved, a chapter now filled in by new maps that detail the mysteries of Sep, GNS, Science, As Zealandia, Gondwana, The Gi and by explainers that present it as Nov, Zealandia, South the underwater eighth continent you did not know about.

A continent fully mapped, but far from fully understood

Even with a complete map in hand, Zealandia remains a frontier. The new datasets provide a framework, but they also highlight how much fieldwork, drilling, and detailed analysis still lie ahead. Many of the continent’s basins have never been sampled, its fault systems are only partly understood, and its role in past climate shifts is still being pieced together from scattered cores and outcrops. In that sense, the mapping is less a final chapter than an opening act.

Researchers at GNS Science describe their achievement as a world first in undersea mapping, but they also stress that the new charts are a starting point for fresh discoveries about the continent. The project that declared Zealandia the first continent to be completely mapped emphasizes that the work is already reshaping questions about its geology, resources, and hazards, and that future expeditions will build on this foundation, a point captured in the detailed description of how Oct, Zealandia just became the first continent to be completely mapped and how that status is already driving new lines of inquiry.

More from MorningOverview