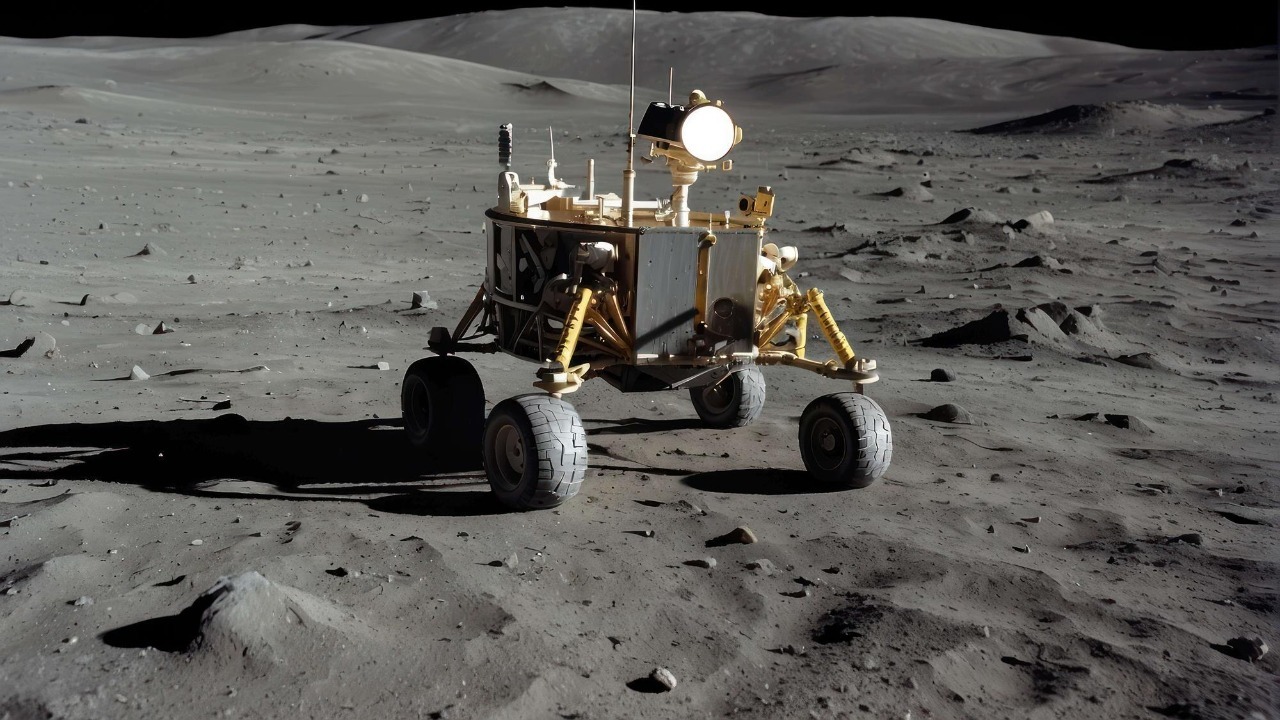

South Korean engineers are stress testing a new kind of lunar robot that is designed to survive the Moon’s most hostile terrain, from jagged crater rims to the sheer walls of underground pits. At the heart of the project is an ultra-rugged, origami-inspired wheel system that can fold, flex, and even drive through fire and extreme cold without losing its shape. The technology is being built with a specific goal in mind: sending machines into the Moon’s caves and lava tubes long before humans follow.

The effort slots neatly into South Korea’s broader push to become a major space power, including plans to build a permanent base on the lunar surface within the next two decades. If the country wants to turn that ambition into a working outpost, it will first need robots that can scout safe havens underground, where future astronauts might find shelter from radiation, temperature swings, and micrometeorite impacts.

Why the Moon’s caves are suddenly a priority

Lunar caves and pits have shifted from scientific curiosity to strategic real estate as space agencies look for places where people and equipment can survive long term. Unlike the exposed plains of the Moon, lava tubes and deep pits can offer natural shielding from solar radiation and wild temperature swings, making them prime candidates for future habitats and storage depots. That is why engineers are now designing robots specifically to reach these hidden spaces instead of treating them as an afterthought.

South Korea has tied this underground frontier directly to its long range lunar agenda, which includes a plan to Build a Base on the Moon and turn it into a lunar economic base by 2045. That vision assumes that robots will first map, sample, and characterize the interior of lava tubes so planners know where to place power systems, habitats, and industrial equipment. In that context, a robot that can drop into a pit, reconfigure its wheels, and keep driving after brutal impacts is not a side project, it is a prerequisite for the country’s long term presence beyond Earth.

The ultra-rugged robot and its brutal test campaign

The new Korean robot is built around a simple idea: if the wheels can survive anything, the rest of the machine has a fighting chance. Engineers have pushed that logic to extremes, subjecting the system to impacts, thermal shocks, and mechanical abuse that go far beyond what most terrestrial vehicles ever see. They have even used a drone to drop the robot from the air, forcing it to absorb hard landings that mimic a fall into a lunar pit or a tumble down a crater wall.

In one series of trials, the team blasted the wheel with open flames and then exposed it to intense cold, demonstrating that the metal structure could keep its shape and function despite rapid temperature swings that would destroy conventional tires. Reporting on the project notes that They also used a drone to drop the robot and highlighted that the metal in the wheel itself is made to withstand these extremes. The goal is not just to prove toughness for its own sake, but to show that a compact, reconfigurable rover can be thrown into the harshest parts of the Moon and still keep moving.

Inside the “space-grade origami airless wheel”

The core innovation behind this robot is a deployable wheel that behaves more like a mechanical sculpture than a traditional tire. Instead of relying on air pressure, the structure uses a carefully tuned pattern of folds and struts that can compress into a small package and then expand into a full size wheel once it reaches the surface. That origami geometry lets the wheel absorb shocks, grip uneven rock, and change its profile depending on the terrain, all without the risk of punctures or leaks.

According to a description from the Department of Aerospace Engineering at KAIST, the project is described as a Major research outcome from Prof. Dae Young Lee and his team, who developed a “Space-Grade Origami Airless Wheel” specifically to enable lunar lava tube entry and interior investigation. By eliminating air and relying on a foldable metal lattice, the wheel can be packed tightly for launch, then deployed into a robust, shock absorbing form once the rover is ready to explore. That combination of compact stowage and rugged performance is exactly what mission designers need when every kilogram and cubic centimeter on a rocket counts.

From lab concept to “first deployable airless wheel”

What sets this Korean effort apart is not just the clever geometry, but the claim that it represents a first of its kind technology for space exploration. The wheel is designed to change shape on command, shifting between a narrow configuration for squeezing through tight gaps and a broader stance for stability on open ground. That reconfigurability gives a two wheeled robot far more versatility than a fixed chassis, especially when it has to navigate both vertical drops and flat cave floors.

A report on the project describes how a Korean team develops origami wheel to help rovers explore moon pits and calls it the first “deployable airless wheel.” That label matters because it signals a shift from static rover designs to machines that can actively reshape themselves to match the environment. In practice, that could mean a robot that lands in a compact form, unfolds its wheels to climb down a pit wall, then tightens its profile again to squeeze through a narrow lava tube entrance.

Why lava tubes demand a new class of rover

Traditional lunar rovers were built for relatively gentle slopes and open plains, not the vertical drops and jagged ledges that define pits and lava tubes. The entrances to these underground structures can be hundreds of meters deep, with overhanging rims and loose regolith that would trap or flip a conventional four wheeled vehicle. Even if a standard rover could be lowered into a pit, it would struggle to climb over boulders and navigate tight turns in the dark interior.

Analyses of future missions point out that the challenge for future lunar rovers lies in accessing the Moon’s lava tubes and pits, which are considered prime candidates for long term bases but present formidable obstacles once deployed. That is why the Korean team is focusing on a two wheeled platform that can use its reconfigurable wheels almost like legs, scaling steep slopes and stepping over obstacles instead of simply rolling along a flat track. The robot is less a miniature car and more a hybrid between a rover and a climber, tailored to the Moon’s most unforgiving terrain.

Performance on regolith, rock, fire, and ice

Designing a clever wheel is one thing, proving that it works on realistic terrain is another. To close that gap, the Korean researchers have run the origami wheel through a battery of tests on simulated lunar regolith, rough rock surfaces, and mixed debris fields that mimic the inside of a pit. The wheel has shown that it can maintain traction on loose dust while still gripping solid rock, a critical combination for any mission that expects to move from the surface into a cave and back again.

Coverage of the project notes that This wheel also demonstrated outstanding performance in test environments, including excellent driving capabilities on slopes and rough terrain. Another technical report highlights that the airless structure can survive a strong impact, such as when using heavy transportation machinery, and can even drive through fire without losing integrity. Those results suggest that the wheel is not just a neat lab prototype, but a candidate for real missions where a single failure could end a multimillion dollar expedition.

Two-wheeled rovers and the case for simplicity

At first glance, a two wheeled rover sounds less stable than the four or six wheeled vehicles that have dominated planetary exploration for decades. The Korean design flips that intuition by using the wheels themselves as multifunctional structures that provide both locomotion and stabilization. By carefully controlling the wheel geometry and the robot’s center of mass, the team can keep the platform upright while it climbs, pivots, and even recovers from partial slips on steep slopes.

Technical analysis of the system describes an Airless wheel that drives through fire and could enable robust, reconfigurable two wheeled lunar rovers. The argument for this architecture is straightforward: fewer wheels mean fewer motors, joints, and failure points, which is especially valuable in the abrasive, vacuum exposed environment of the Moon. If the wheels can change shape to handle different tasks, a minimalist chassis can still tackle complex terrain, reducing both mass and mechanical complexity for future missions.

How this fits into South Korea’s broader lunar roadmap

The origami wheel project is not happening in isolation, it is part of a broader national strategy to move from first missions to permanent infrastructure on the Moon. South Korea has already demonstrated its ability to reach lunar orbit with the Korea Pathfinder Lunar Orbiter, known as Danuri, which launched in August 2022 and began mapping the surface for future missions. That spacecraft has been gathering data on potential landing sites, resource rich regions, and communication conditions, all of which feed into planning for surface operations.

Strategic documents describe how, In August, the Korea Pathfinder Lunar Orbiter Danuri was launched to support a long term goal of building a moon base by 2045. Parallel to that, South Korea Plans to expand its domestic space industry, with Jul marking a political commitment to invest in technologies that can support a lunar economic base. In that context, a robot capable of scouting lava tubes is a logical next step, providing the ground truth needed to decide where to place habitats, power systems, and industrial facilities that could eventually support mining, science, and tourism.

The rise of Korea’s private rover builders

Government backed research institutes and universities are not the only players in this story. Private companies in South Korea are also positioning themselves as key suppliers of lunar hardware, from small rovers to specialized instruments. These firms see an opportunity to carve out niches in navigation, mobility, and autonomous operations that can plug into both national missions and international partnerships.

One example is highlighted in a profile of how Korea’s First Space Rover Developer Aims for a 2032 Lunar Mission, led by Namsuk Cho, CEO of the Unmanned Exploration Laboratory. That company is developing its own rover platforms while targeting niche fields like space tech, suggesting a future in which university labs, private firms, and national agencies collaborate on modular systems. In such a landscape, the origami wheel could become one component in a broader ecosystem of Korean built robots, each optimized for different tasks but sharing common technologies and design philosophies.

More from MorningOverview