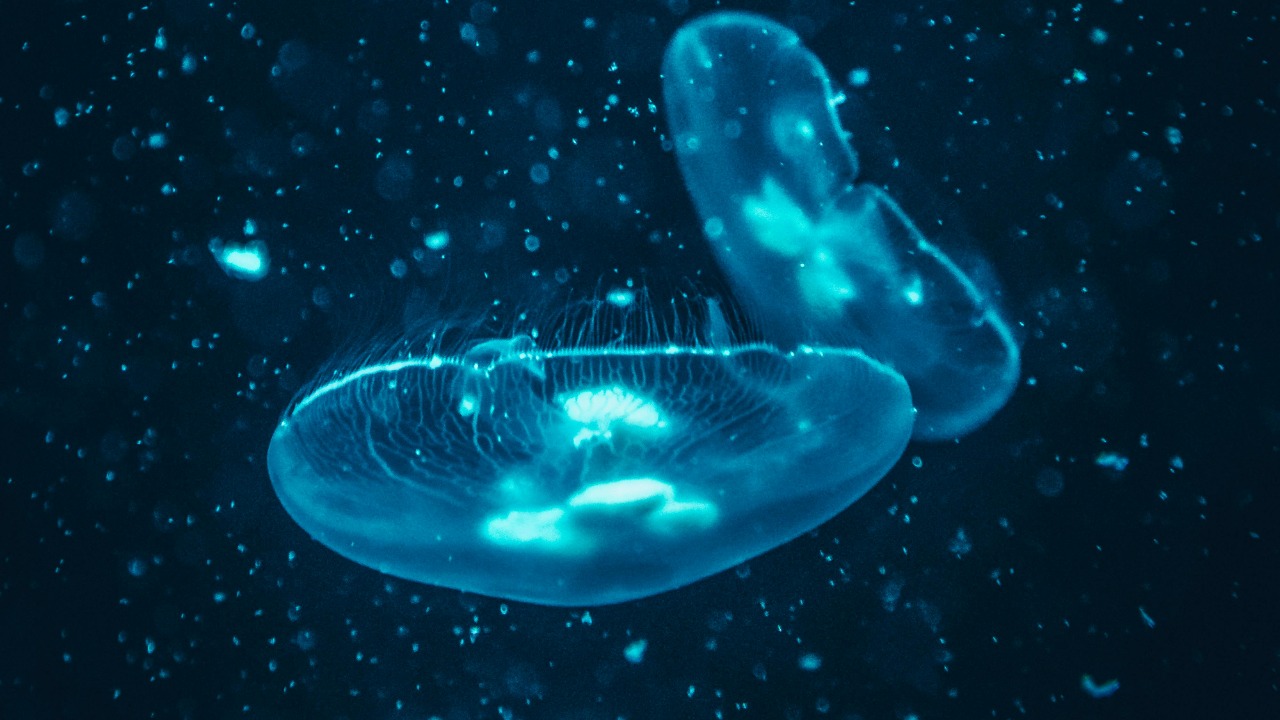

Beachgoers on a popular stretch of U.S. coastline have been stopping in their tracks at the sight of translucent, blue and white blobs scattered along the high-tide line. The creatures look almost ornamental, but marine specialists say they are a warning sign that the ocean is changing in ways that bring animals into places they do not naturally belong. When experts say these strange visitors “shouldn’t be here,” they are talking about more than geography, they are flagging a collision between warming seas, global shipping and a stressed coastal food web.

‘They are beautiful’ – and a red flag

When I talk to marine biologists about odd strandings, they almost always start with the same tension: the animals are stunning, and they are also a problem. That is the case with the unfamiliar jelly-like organisms that recently washed up on a U.S. beach, prompting specialists to warn that the creatures “don’t belong here” even as they described how “beautiful” they looked in the surf. The concern is not that one or two drifters arrived on a current, but that a whole group of these newcomers appeared together, a pattern that suggests a shift in currents, temperature or human activity that helped them cross natural barriers.

Scientists tracing these arrivals have pointed to global shipping as a likely vector, with larvae and tiny adults transported in ballast water that is taken on in one port and released in another. In the case of the Texas sighting, experts linked the animals to an invasive jellyfish that is native to Australian waters and that specialists say is being introduced through ballast water. When a species that evolved in one hemisphere suddenly appears in another, it can outcompete local plankton feeders, sting unsuspecting swimmers and alter the balance of predators and prey that coastal communities depend on.

From Texas to Australia, a pattern of painful arrivals

What is happening on that U.S. shoreline fits into a broader pattern of gelatinous drifters turning up in places where people are not used to seeing them. I have heard lifeguards describe days when the water seems to be “alive” with stinging tentacles, and that image matches reports from Australian beaches where blue, sail-topped organisms have arrived in such numbers that locals say they are “terrorising us.” Those animals, known as bluebottles, are not true jellyfish but colonial hydrozoans that can deliver painful stings and force beach closures when the wind and currents push them ashore in “gobsmacking numbers.”

Bluebottles are part of a complex open-ocean community, and they are themselves preyed upon by a striking predator called Glaucus, a small nudibranch nicknamed the “sea lizard” or “Pokémon slug” for its vivid blue markings. When bluebottles and their predators wash ashore together, they remind coastal residents that what looks like a simple blob on the sand is actually part of a food chain that stretches across ocean basins. The Texas experts who flagged their own “beautiful” but out-of-place visitors are effectively warning that a similar offshore drama may now be unfolding in the Gulf of Mexico, with unfamiliar stingers and their hunters arriving in tandem.

‘Work of art’ on the sand, shock in the surf

For people encountering these creatures for the first time, the reaction is often a mix of awe and unease. In one recent video from the East Coast, beachgoer Natasha Kimmel stands over a cluster of bright blue animals and says you could look at each one “as a work of art,” before adding that it is simply “part of nature” washing ashore. I have heard that same tone from parents trying to decide whether to let their children touch a stranded jelly or steer them away, torn between curiosity and the fear of a sting.

Experts I speak with say that tension is exactly why they want people to recognize that some of these arrivals are not just seasonal visitors but species that have crossed an ocean. When a local community sees a strange creature as a one-off curiosity, it is easy to shrug and move on. When they understand that a cluster of blue, sail-topped drifters or white-spotted jellies might signal a broader shift in currents or shipping patterns, they are more likely to support monitoring programs and ballast water rules that can slow the spread of invasive species.

Giant fish and deep-sea myths

Not every strange animal on a U.S. beach is a jelly-like drifter. Sometimes the surprise is a single, massive fish that looks like it belongs in a science fiction film rather than on a local shoreline. Marine biologists still talk about the day a gigantic sunfish, described as an over-sized version of what you might see in a home aquarium, washed ashore on a Southern California beach. The animal turned out to be a species that specialists had not previously confirmed in North American waters, a reminder that even large vertebrates can turn up far from home when currents, storms or injuries push them off course.

Researchers who examined that specimen said it had traveled “a long way from home” and noted that, based on its body shape and DNA, it matched a type of sunfish that had been documented in the Southern Hemisphere. One scientist explained that “we know it has the ability to move long distances,” which helps explain how it could end up so far north, but that did not make its appearance on a California beach any less startling. The bizarre fish joined a growing list of “out of place” animals that force scientists to revisit assumptions about where a species lives and how often it crosses invisible lines on the map.

Oarfish, folklore and what strandings really mean

Few marine animals capture the public imagination like the oarfish, a long, ribbon-like creature that can grow to 30 feet in length and that has fueled legends of sea serpents for centuries. When one of these silvery giants washes ashore, social media fills with speculation about earthquakes and omens, and I have seen people share old stories that link oarfish to impending disasters. Scientists who study the species offer a more grounded explanation, pointing out that these fish typically live in deep water and only end up on beaches when they are injured or disoriented.

Researchers who have examined stranded specimens in California and Japan say the animals feed on krill and other small prey in the midwater zone, far below the surface chop that most swimmers experience. When an oarfish appears in the surf, it is usually a sign that something has gone wrong for that individual, not that the ocean as a whole is sending a message. A recent analysis of oarfish folklore emphasized that while these strandings are rare and dramatic, they are best understood as data points in a long record of deep-sea animals occasionally crossing into human view, not as reliable predictors of seismic events.

Velella and the Northern California ‘purple tide’

On the other end of the size spectrum from oarfish are the palm-sized drifters that sometimes blanket West Coast beaches in a purple-blue tide line. In the chilly waters off the Northern California coast, these animals, known as Velella velella, float along the surface with a tiny sail that catches the wind. When conditions are right, they can arrive in such numbers that local residents describe the sand as carpeted with translucent bodies, each one a small colony of polyps that normally lives far offshore. The sight is striking, but it also raises questions about how wind patterns and ocean temperatures are shifting.

Marine specialists who track Velella say that while these strandings are a natural part of the species’ life cycle, the timing and scale of recent events suggest that the underlying conditions are changing. When a strong onshore wind coincides with a bloom of surface drifters, thousands can be pushed onto beaches like Marin County’s Bolinas Beach in a single weekend. For coastal managers, that kind of event is both a public curiosity and a logistical challenge, since the stranded animals quickly begin to decompose and can create a smell that drives visitors away. The same dynamics that bring Velella ashore can also influence where other gelatinous species, including invasive jellies, end up along the U.S. coastline.

Plastic rafts and a rewired food web

Beyond currents and wind, one of the most significant new forces shaping where sea creatures appear is the spread of floating plastic. I have heard oceanographers describe the North Pacific as a patchwork of natural debris and synthetic trash, and that mix is changing how animals move and feed. Tiny marine insects that once laid their eggs only on driftwood or pumice now use plastic fragments as nesting sites, effectively turning bottles and bags into mobile nurseries. That shift gives some species more places to reproduce, which can increase their numbers and alter who eats whom at the surface.

Researchers who study the Pacific’s growing plastic problem say this new habitat is not neutral. When insects and other small animals colonize floating trash, they attract predators that would not otherwise spend time in those areas, and the result is a reshaped food web that can ripple down to fish and larger animals. One analysis found that Researchers think plastic gives insects another place to lay their eggs, which in turn changes how surface animals interact and can upset the ocean’s natural food web. When that artificial raft of life drifts toward shore, it can carry hitchhiking species into bays and estuaries where they have never been seen before, setting the stage for more “shouldn’t be here” moments on local beaches.

Comb jellies, boom-and-bust invasions

Among the most disruptive newcomers in coastal ecosystems are comb jellies, translucent predators that look harmless but can transform a food web when they arrive in force. I have heard fisheries scientists describe how a single invasive comb jelly species can bloom so intensely that it strips plankton from the water, leaving little for native fish larvae and other grazers. These animals do not just eat other species, they also consume their own young, a behavior that helps drive dramatic boom-and-bust cycles in their populations.

Studies of invasive comb jellies in enclosed seas have shown that these bloom-and-bust events have huge downstream effects on local food webs, decimating the prey that other sea creatures rely on and contributing to collapses in fish stocks. One recent investigation into their feeding habits found that adults routinely cannibalize their own larvae, a strategy that may help them survive when food is scarce but that also makes their population dynamics hard to predict. The researchers behind that work, published in the journal Aquatic Invasions, concluded that these invasive “comb jellies” can trigger cascading changes that extend far beyond the immediate area where they first appear. When a beach suddenly fills with unfamiliar, shimmering blobs, that spectacle may be the visible edge of a much larger ecological disturbance unfolding just offshore.

How coastal communities should respond

For people who live and work along the coast, the growing list of strange strandings is not just a curiosity, it is a practical challenge. Lifeguards, shellfish harvesters and tourism operators all have to decide how to respond when a new species shows up in the surf, especially if it can sting swimmers or clog fishing gear. I have seen communities move from ad hoc reactions to more systematic approaches, training staff to photograph and report unusual animals, posting clear signage about stinging species and working with scientists to identify which arrivals are harmless drifters and which are invasive threats.

Experts who study these events say the most effective responses combine local observation with broader policy changes. On the ground, that means encouraging beachgoers to admire unfamiliar creatures without touching them, to keep pets away from stranded jellies and to share images with regional monitoring programs that can track new arrivals. At the policy level, it means tightening ballast water rules that allowed the Australian white-spotted jellyfish to reach Texas, supporting research into how plastic rafts are moving species across oceans and investing in early warning systems that can flag comb jelly blooms before they devastate fisheries. When specialists say a creature “shouldn’t be here,” they are not just describing a surprise on the sand, they are inviting coastal communities to help decide what kind of ocean they want lapping at their shores.

More from MorningOverview