A vanishingly rare genetic glitch in a single enzyme can erase a newborn’s brain cells in a matter of weeks, leaving doctors with almost no way to intervene. Researchers have now traced that devastation to a precise molecular trigger, revealing how a subtle structural flaw in a protective protein flips neurons into a self-destruct mode. The discovery not only clarifies why this mutation is so lethal, it also exposes a hidden vulnerability that could be relevant to far more common forms of dementia.

The ultra-rare disorder that first raised alarms

The mystery starts with an ultra-rare skeletal and neurological condition that strikes in the first days of life. In humans, this specific ultra-rare genetic disorder is called Sedaghatian-type spondylometaphyseal dysplasia, or SSMD, and it combines severe bone abnormalities with catastrophic damage to the nervous system. Babies with Sedaghatian features are typically born with profound muscle weakness, breathing problems, and signs that their brains are already under assault, a pattern that has long suggested a fundamental defect in how their neurons stay alive.

Clinicians have known that SSMD is inherited, but until recently they could only watch as the condition unfolded. Reports describe infants with this diagnosis losing neurological function rapidly, with many dying in early infancy despite intensive care. The combination of skeletal deformities and brain failure made SSMD a grim outlier among pediatric disorders, yet it also offered a stark window into what happens when a core survival pathway in neurons is knocked out from birth.

A single enzyme, GPX4, sits at the center of the storm

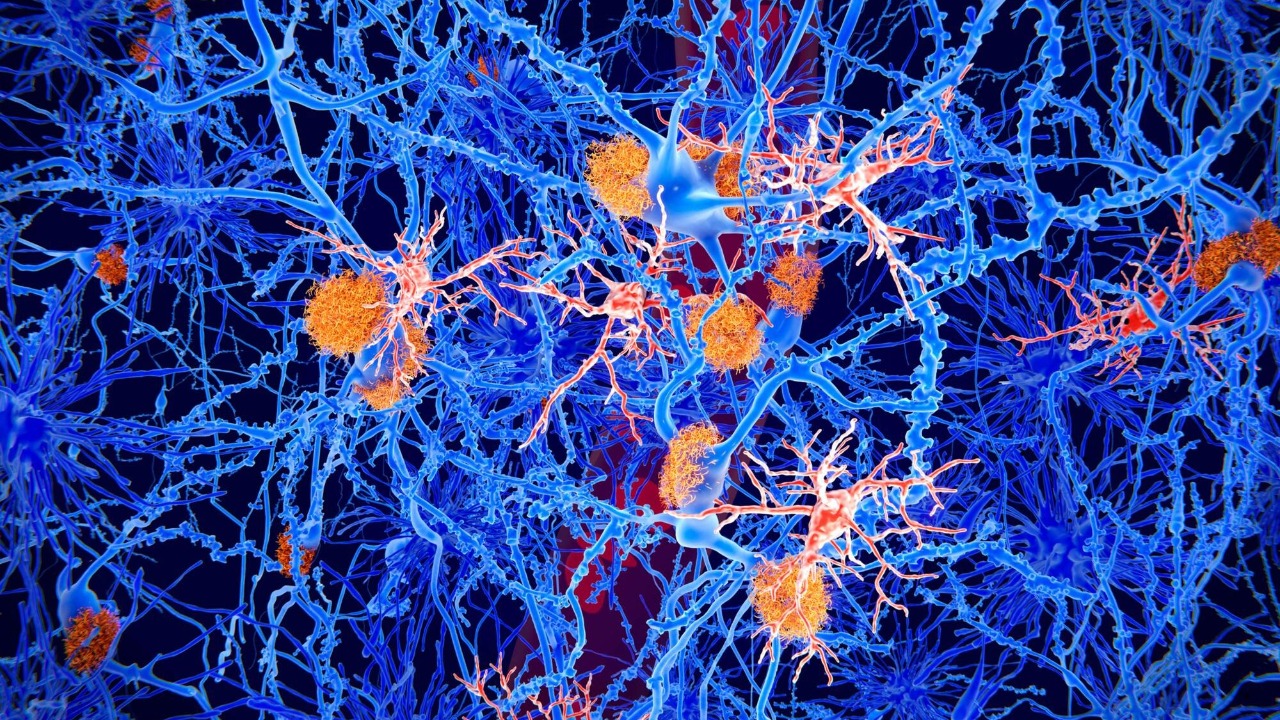

At the molecular level, the trail leads to one enzyme that normally acts as a guardian inside brain cells. That protein, called glutathione peroxidase 4, or GPX4, helps detoxify reactive molecules that would otherwise chew through the fatty membranes surrounding neurons. Earlier this month, researchers reported that a tiny structural feature of GPX4 is crucial for this protective role, and that a rare mutation which removes this feature can be enough to unleash widespread neuronal death.

In the SSMD families that have been studied, the GPX4 gene carries an ultra-rare change that subtly alters the enzyme’s architecture. On paper, the mutation looks modest, but in living cells it appears to cripple a key part of the enzyme’s function. When scientists examined neurons carrying this altered GPX4, they saw a pattern of damage that matched the rapid degeneration seen in affected infants, tying the clinical syndrome directly to a single molecular failure.

The hidden structural flaw that flips neurons into ferroptosis

The new work drills down to an almost atomic level to explain how that failure unfolds. Using structural and biochemical tools, researchers discovered that a tiny structural feature of GPX4, essentially a small protruding element on the enzyme’s surface, is indispensable for keeping neurons safe. The Sedaghatian-linked mutation removes or distorts this feature, leaving GPX4 unable to interact properly with the lipid molecules it is supposed to protect.

Without that structural safeguard, neurons are pushed into a specific form of cell death known as ferroptosis, which is driven by iron-dependent lipid damage. The study provides the first molecular evidence that a single enzyme defect can directly trigger ferroptosis in human brain tissue, turning a once-theoretical pathway into a concrete mechanism. In cells derived from an SSMD patient, the mutated GPX4 failed to stop this cascade, and neurons succumbed in a way that mirrored the clinical course seen in the infants.

From rare infant tragedy to broader dementia clues

Although SSMD affects only a tiny number of families worldwide, its biology reaches far beyond this one diagnosis. The same ferroptosis pathway that destroys neurons in Sedaghatian-type spondylometaphyseal dysplasia has been implicated in more common neurodegenerative conditions, including forms of dementia. In a detailed analysis of patient-derived cells, scientists showed that the GPX4 mutation in SSMD unleashes a wave of lipid peroxidation, strengthening the case that ferroptosis is not just a laboratory curiosity but a real driver of human brain disease.

One report on this rare genetic mutation notes that ferroptosis is linked to Alzheimer’s, suggesting that the same destructive chemistry may be at work in late-life memory loss as in early-onset childhood dementia. By tying a concrete human mutation to this pathway, the SSMD findings give researchers a sharper tool for probing how ferroptosis might contribute to more prevalent conditions, and for testing whether blocking it can slow or prevent neuron loss.

What Sedaghatian-type SSMD does to a child’s body

For families, the science is inseparable from the brutal clinical reality. In humans, this specific ultra-rare genetic disorder is called Sedaghatian-type spondylometaphyseal dysplasia, or Sedaghatian, and it is associated with children dying in early infancy. The skeletal component of SSMD includes severe curvature and shortening of the long bones, along with abnormalities in the spine and ribs that can compromise breathing. These structural problems are visible on imaging soon after birth, but they are only part of the syndrome’s impact.

Neurologically, SSMD overlaps with other devastating early-life conditions in its trajectory, even if the underlying gene is different. In related disorders cataloged in genetic databases, most patients die in the first years of life, and those that survive have spastic quadriplegia, feeding difficulties necessitating tube feeding, cortical blindness, nystagmus, scoliosis, and hearing impairment, a pattern summarized in one MedGen entry that captures the scale of neurological loss. SSMD sits at the extreme end of this spectrum, with GPX4 failure adding a rapid, biochemical assault on neurons to an already heavy burden of structural disease.

How GPX4 normally shields the brain from oxidative damage

To understand why a single mutation is so catastrophic, it helps to look at what GPX4 is supposed to do. In healthy neurons, this enzyme uses the antioxidant glutathione to neutralize peroxides that form when fats in cell membranes react with oxygen. A detailed overview from By Helmholtz Munich December describes how a tiny flaw in this brain-protective enzyme can remove a crucial part of the enzyme’s function, leaving neurons exposed to oxidative stress that they would normally survive.

In the context of SSMD, the GPX4 mutation effectively removes that shield from the very start of life. Instead of quietly mopping up reactive molecules, the defective enzyme lets them accumulate, particularly in the lipid-rich membranes that insulate nerve fibers. Once that process crosses a threshold, ferroptosis kicks in, and neurons begin to die in clusters rather than one by one. The new findings show that this is not a slow, age-related drift but a rapid cascade that can unfold in the first weeks after birth when GPX4 is compromised.

Inside the lab: recreating SSMD in cells and models

To move from correlation to causation, scientists needed to recreate the SSMD mutation in controlled systems. They introduced the Sedaghatian-linked GPX4 variant into cultured neurons and organoid models, then watched how the cells responded to oxidative stress. Compared with cells carrying normal GPX4, the mutated neurons showed a dramatic increase in lipid peroxidation and a sharp rise in ferroptotic cell death, mirroring the pattern seen in tissue samples from an SSMD patient.

One institutional summary of the work notes that the study provides the first molecular evidence that ferroptosis can drive neurodegeneration in the human brain, particularly for severe early-onset childhood dementia, a point highlighted in a research briefing. By toggling ferroptosis inhibitors on and off in these models, the team could show that blocking this specific death pathway rescued neurons with the GPX4 mutation, at least in the dish, strengthening the argument that ferroptosis is the key trigger rather than a side effect.

What Marcus Conrad’s “brake” analogy reveals about treatment

For Marcus Conrad, a cell biologist and director of the Institute of Metabolism and Cell Death at Helmholtz Munich, the GPX4 story is as much about prevention as it is about damage. In his description of the work, he likens GPX4 to a brake that keeps ferroptosis from starting in the first place, a metaphor that captures how the enzyme restrains a destructive process that is always lurking in the background. When that brake is removed by mutation, the car does not just slow less efficiently, it hurtles forward into a crash.

Conrad’s framing, shared in a recent interview, underscores why therapies that simply clean up after the fact may not be enough. If GPX4 is the brake, then drugs that mimic its action or stabilize its structure could, in theory, prevent ferroptosis from being set in motion at all. For SSMD families, that remains a distant hope, but the concept is already influencing how researchers think about protecting neurons in other conditions where ferroptosis appears to be active.

Parallels with other lethal childhood neurodegenerative diseases

SSMD is not the only diagnosis where a single genetic change can erase motor neurons in infancy. In the most severe form of spinal muscular atrophy, for example, patients rapidly lose motor neurons and symptoms such as muscle weakness and delayed development appear in the first months of life, a pattern described in detail in a Novartis overview. That same report notes that this form of spinal muscular atrophy is a leading genetic cause of infant and toddler deaths, underscoring how fragile early neuronal survival can be when a core pathway is disrupted.

What sets SSMD apart is the specific mechanism of ferroptosis, rather than the loss of a structural protein or motor neuron maintenance factor. Yet the clinical parallels with spinal muscular atrophy and related disorders highlight a broader pattern in pediatric neurology, where a single gene can dictate whether a child’s nervous system develops at all. By mapping the GPX4 mutation in Sedaghatian-type spondylometaphyseal dysplasia onto this landscape, researchers can compare how different death pathways, from ferroptosis to apoptosis, shape the course of early-life brain disease and potentially identify shared intervention points.

Why a rare mutation matters for future dementia drugs

The immediate impact of the GPX4 discovery is on how scientists think about SSMD, but the longer-term stakes lie in dementia research. A detailed feature on this rare mutation emphasizes that ferroptosis is linked to Alzheimer’s, raising the possibility that subtle, acquired changes in GPX4 function, or in related antioxidant systems, could contribute to neuron loss in older adults. If that is true, then drugs designed to boost GPX4 activity or to block ferroptosis might have a role far beyond a handful of Sedaghatian cases.

For now, the path from bench to bedside is uncertain, and any therapy for SSMD itself would need to act extremely early, perhaps even before birth, to prevent the first wave of neuronal death. Yet the conceptual shift is already underway. By showing that a tiny structural flaw in a single enzyme can wipe out brain cells through a defined biochemical trigger, the GPX4 work gives dementia researchers a new target to probe and a clearer sense of how protecting neurons from oxidative damage might translate into real-world treatments.

More from MorningOverview