For more than two centuries, astronomers have treated the Sun’s spectrum as a solved problem, a textbook example of how light reveals the chemistry of the cosmos. Now a fresh look at that familiar rainbow has exposed something far stranger: entire colors appear to be missing in ways that do not match any known atom or molecule. The discovery turns a supposedly mature field into an active mystery, forcing scientists to admit that even the nearest star still holds secrets in plain sight.

At stake is not just a curiosity about how the Sun shines, but a core tool of modern astrophysics. If I cannot fully explain the fingerprints in our own star’s light, every spectrum from a distant exoplanet, galaxy, or nebula suddenly looks less certain. The puzzle of the missing colors is a reminder that the universe can still surprise us most where we think we understand it best.

How a 200‑year‑old technique suddenly raised new questions

When physicists first split sunlight with a prism in the 1800s, they saw a smooth band of color interrupted by dark lines, each one a sign that specific wavelengths were being absorbed by atoms in the solar atmosphere. Over time those lines became the foundation of stellar physics, letting researchers measure temperature, composition, and motion from nothing more than a spectrum on a detector. After roughly 200 Years of Study, the assumption was that the Sun’s light had been mapped and cataloged to the point of boredom.

That confidence is exactly what makes the new anomaly so jarring. When scientists assembled one of the most detailed solar spectra ever recorded, they expected to refine existing measurements, not stumble on features that simply do not fit the playbook. Instead they found that some parts of the spectrum are oddly depleted, as if something is erasing narrow slices of color in ways that cannot yet be traced to any familiar process. The result is a quiet but profound shift: the Sun’s spectrum is no longer just a solved reference, it is an active crime scene where some of the culprits are still unknown.

What it means for colors to be “missing” from the Sun

To a casual observer, the Sun looks like a uniform white disk in the sky, or a warm yellow ball in children’s drawings, but its light is far more structured than that. When I spread that light into a spectrum, I see that it is brightest at yellow‑green wavelengths, even though the Sun’s rays cover everything from deep red to violet and beyond. Within that smooth curve sit thousands of tiny gaps, places where specific colors are weaker than they should be because atoms and molecules have absorbed them before the light escapes, leaving what look like missing pieces in the rainbow.

Most of those gaps are well understood, each one tied to a known transition in hydrogen, helium, iron, or other elements that populate the solar atmosphere. The new work, however, highlights a subset of features that do not line up with any cataloged species, even when researchers account for overlapping fingerprints and complex blends. In other words, there are colors missing from the Sun that cannot yet be matched to any known absorber, a conclusion that emerges clearly when scientists compare the observed spectrum to models and see persistent, unexplained deficits in particular wavelength bands.

The Sun’s spectrum as a forest of fingerprints

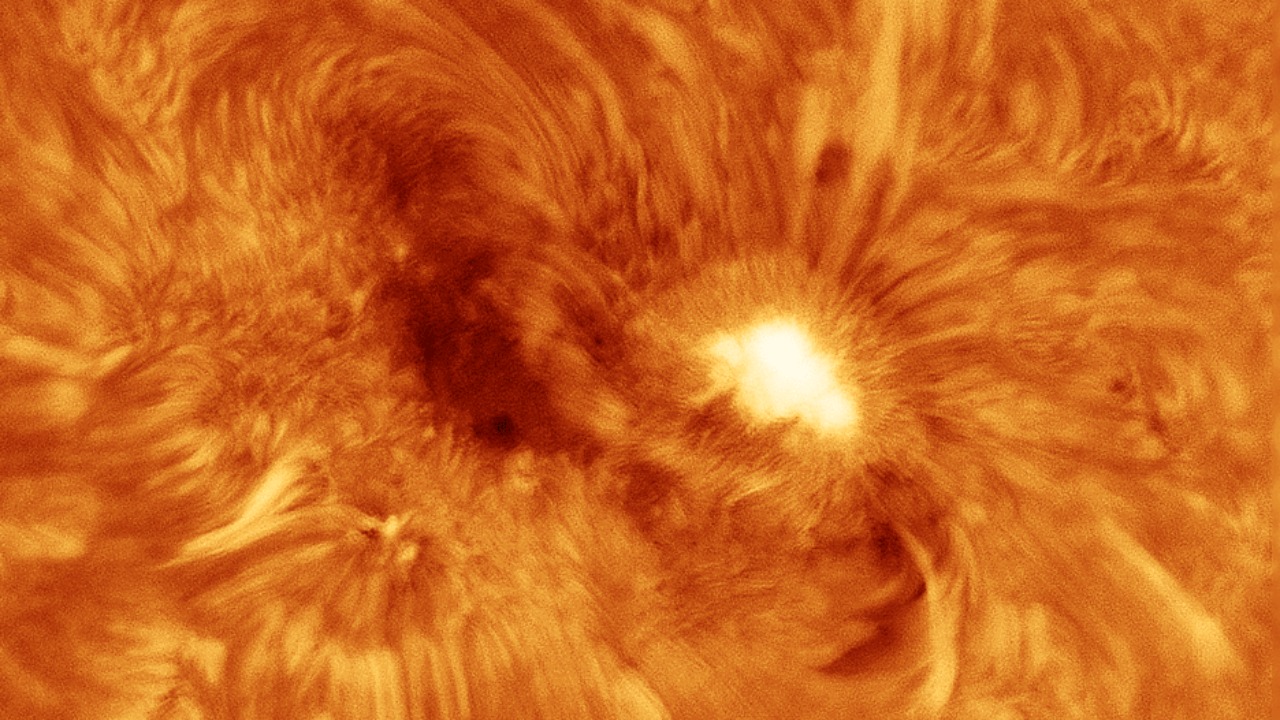

One of the most striking ways to visualize this problem is to treat the spectrum as a dense forest of fingerprints, each line a clue to some physical process in the solar atmosphere. In composite images of the Sun captured in three different colors, structures like sunspots and active regions pop out, but the real forensic power lies in the fine‑grained pattern of absorption features. One of the most detailed views shows that the light is not just a smooth gradient, it is a barcode of physics, with every notch and groove encoding temperature, pressure, and composition in the layers where the photons last interacted with matter.

When I zoom in on that barcode, I see that some fingerprints are crisp and isolated, while others overlap and blur together, making it hard to tell which atom is responsible for which dip in brightness. That complexity is part of why the new missing colors are so intriguing: even after accounting for known overlaps, some features remain stubbornly unassigned. The Sun, which should be the best‑calibrated light source in astronomy, turns out to have spectral marks that look like they belong to something we have not yet identified, challenging the idea that the solar spectrum is a fully decoded reference.

Why familiar physics cannot yet explain the anomaly

At first glance, it might be tempting to blame the unexplained gaps on mundane issues like instrument noise, calibration errors, or incomplete data reduction. Researchers have tested those possibilities, cross‑checking different telescopes and analysis pipelines to see whether the odd features persist. The stubborn conclusion is that the missing colors appear to be real properties of the Sun’s light, not artifacts of the hardware or software, which raises a more unsettling possibility: the standard list of solar absorbers may simply be incomplete.

In principle, every absorption line should correspond to a specific transition in a specific atom, ion, or molecule, but that neat mapping depends on laboratory measurements that are still a work in progress. Determining the spectral fingerprint of a given species often requires painstaking experiments under controlled conditions, and some combinations of temperature, pressure, and ionization that exist in the Sun are hard to reproduce on Earth. The unexplained features suggest that there are still gaps in those laboratory catalogs, or that some solar processes generate absorption in ways that current models do not capture, leaving a residue of lines that do not yet have names.

How scientists hunt for the source of the missing colors

To track down the origin of the unexplained features, researchers start by comparing the Sun’s spectrum to theoretical models that include every known element and molecule at realistic temperatures and densities. When the models fail to reproduce certain dips in brightness, the team systematically varies parameters like magnetic field strength, turbulence, and atmospheric structure to see whether any combination can account for the anomalies. This is a kind of astrophysical detective work, where each adjustment either brings the synthetic spectrum closer to reality or rules out a class of explanations, narrowing the field of suspects behind the missing colors.

In parallel, laboratory physicists work to expand the library of known fingerprints by heating gases, ionizing them, and recording the light they absorb or emit under different conditions. That process is slow and technically demanding, especially for complex ions or transient molecules that exist only briefly in hot plasmas. As a result, some of the Sun’s spectral lines remain unsolved, their chemical origins unknown even after decades of effort, and the newly highlighted gaps underscore just how incomplete the current database still is. Until those lab measurements catch up, the Sun’s spectrum will continue to contain features that resist classification, serving as a standing challenge to both experimental and theoretical physics.

What the mystery reveals about the limits of solar knowledge

The fact that there are still unidentified lines in the spectrum of the nearest star is a humbling reminder of how much remains to be learned about even the most familiar objects in the sky. For years, solar physics has been treated as a mature discipline, with textbooks presenting the Sun as a solved example while attention shifted to more exotic targets like black holes and exoplanets. The discovery that some colors are missing in ways we cannot yet explain forces a reappraisal of that hierarchy, suggesting that the Sun still has the power to surprise us and to expose blind spots in our understanding of high‑temperature plasmas.

Those blind spots matter because the Sun is the benchmark against which astronomers calibrate their tools for studying other stars and planetary systems. If I cannot fully decode the spectrum of The Sun, then interpreting the light from a distant world’s atmosphere becomes more uncertain, especially when I am looking for subtle signatures like water vapor or biosignature gases. The unresolved lines in the solar spectrum therefore act as a warning label on the broader enterprise of spectral analysis, signaling that some of the assumptions baked into models and retrieval algorithms may need to be revisited in light of the new evidence.

Why the puzzle matters beyond pure curiosity

On the surface, the idea that a few narrow bands of color are missing from sunlight might sound like an esoteric detail, the kind of thing that only spectroscopists would care about. In practice, those details ripple outward into many areas of astrophysics and even into practical technologies that rely on precise knowledge of solar radiation. Climate models, for example, depend on accurate solar spectra to calculate how energy is absorbed and scattered in Earth’s atmosphere, and any systematic error in those inputs can subtly skew projections of temperature and circulation patterns over long timescales.

There is also a more philosophical stake in the story, one that speaks to how science progresses. For generations, the Sun’s spectrum has been held up as a triumph of physics, a case where theory and observation lined up so well that the problem was considered essentially closed. The emergence of a new discrepancy, captured in the phrase There Are Colors Missing From the Sun and Scientists Don Know Why, shows that even the most celebrated successes can harbor unresolved questions. That is not a failure of the scientific method, it is a sign that the method is working, revealing its own limits and pointing researchers toward the next frontier.

How the new findings reshape a classic solar puzzle

The recognition that There Are Colors Missing From The Sun, And We Still Can Fully Explain Why, does not erase the progress made over the past two centuries, but it does reframe an old puzzle in sharper terms. Earlier work had already noted that some solar lines were hard to assign, yet those anomalies were often treated as minor bookkeeping issues rather than as clues to deeper physics. By assembling more detailed spectra and highlighting the stubbornly unexplained features, the latest analyses elevate those loose ends into central questions, inviting fresh scrutiny from both observers and theorists.

In that sense, the Sun has shifted from being a static reference to a dynamic laboratory where new phenomena can be discovered simply by looking more closely at familiar data. One you may notice immediately is that the light is brightest at yellow‑green wavelengths, a detail that once seemed trivial but now feeds into more nuanced models of how energy moves through the solar atmosphere and emerges as radiation. As I follow the trail of missing colors through those models, I see not just a technical challenge, but an opportunity to refine the entire framework that connects atomic physics, plasma dynamics, and the light that ultimately reaches Earth.

Why the search for answers will take time

Even with modern instruments and powerful computers, solving the mystery of the missing colors will not be quick. Determining the spectral fingerprint of a specific atom or molecule often requires testing and verification across a range of conditions, and some of the relevant species may only exist in the extreme environments found near the Sun’s surface. That means laboratory teams must design experiments that push equipment to its limits, while theorists develop quantum‑mechanical calculations to predict lines that have not yet been measured, a process that can take years for a single complex ion.

In the meantime, astronomers will keep mining existing solar data for patterns that might hint at the nature of the unknown absorbers, looking for correlations with magnetic activity, sunspot cycles, or changes in the outer atmosphere. Each new clue will help narrow the list of possibilities, but it is likely that some features will remain unexplained for quite some time, serving as a standing reminder that the Sun still holds unsolved problems. For me, that is a marvelous thing too, because it means that even in a field as well trodden as solar spectroscopy, there is still room for genuine discovery every time we split sunlight into its constituent colors.

More from MorningOverview