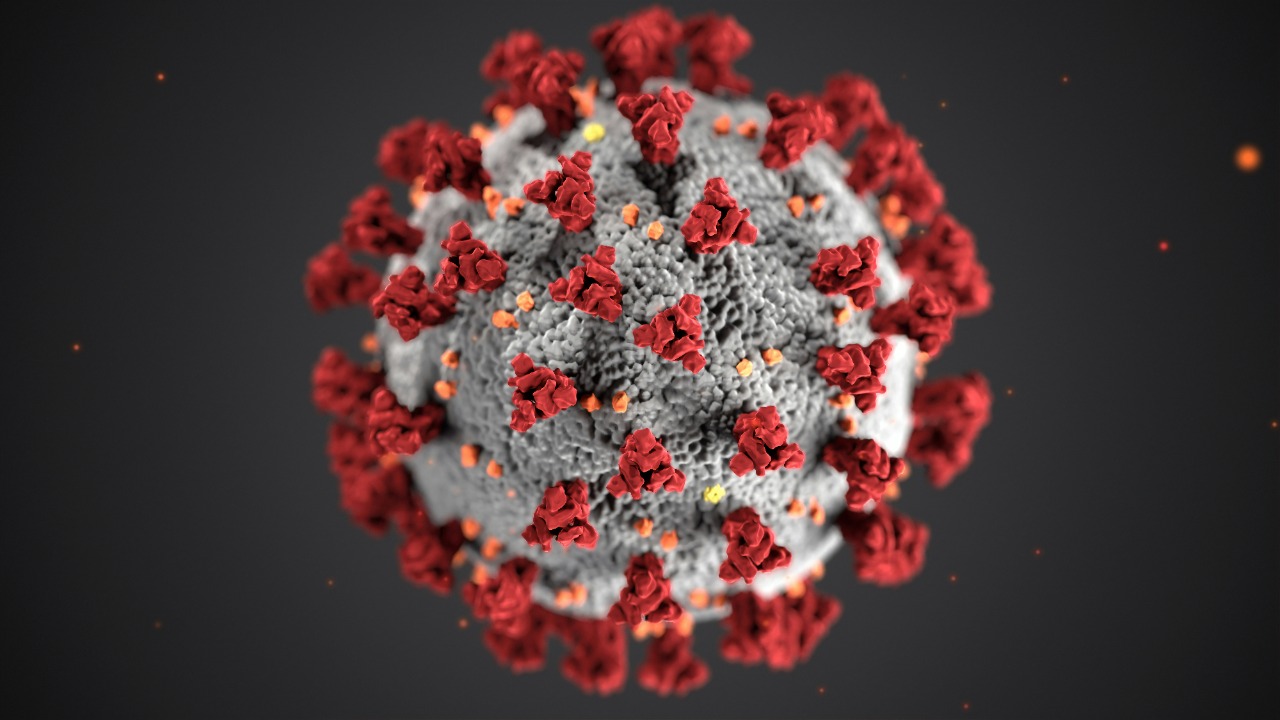

Long COVID has lingered as one of the most unsettling legacies of the pandemic, a condition that can derail lives long after the initial fever and cough fade. A growing body of research now points to a deceptively simple but radical possibility: in many patients, the virus or other microbes never fully left, instead hiding in tissues and quietly stoking chronic illness. If that is true, then tracking down and treating these hidden infections could be the missing key to Long COVID.

I see this shift as more than a scientific curiosity. It reframes long-term symptoms from a vague post-viral syndrome into a problem of ongoing infection and immune disruption, one that might finally be vulnerable to targeted drugs, monoclonal antibodies, and even vaccines against other pathogens that COVID may have stirred awake.

From mystery illness to microbial suspects

For years, Long COVID was often described in broad strokes, a grab bag of fatigue, brain fog, chest pain, and digestive trouble that seemed to defy neat explanation. That picture is starting to sharpen as Dec scientists map out a network of viral suspects, including SARS-CoV-2 itself and other pathogens that may be reactivated or newly acquired in the wake of infection. In new work highlighted by Scientists, researchers describe how COVID can disturb immune defenses in ways that let latent viruses and bacteria flare, creating a layered illness rather than a single-hit event.

That shift in thinking matters because it suggests Long COVID is not just about damage left behind, but about something still happening inside the body. Instead of treating patients as if they are recovering from a storm that has already passed, clinicians are beginning to look for ongoing viral activity, reservoirs of SARS-CoV-2, and signs that other microbes have taken advantage of the chaos. The emerging hypothesis is that hidden infections, sometimes in multiple tissues at once, could be driving persistent symptoms and might be detectable and treatable if we know where to look.

Viral persistence: when SARS-CoV-2 refuses to leave

The most direct version of the hidden infection theory is also the most unsettling: that SARS-CoV-2 itself can linger in the body for months or even years. Earlier research showed that the COVID virus can remain in tissues long after nasal swabs turn negative, and new work has strengthened that case. One study found that the New evidence of viral material persisting more than a year was present even in otherwise healthy people, and that the CO virus can be detected in people with Long COVID as well as in those who never developed chronic symptoms.

Clinicians at major centers have been tracking similar signals. In a broad review of patients five years into the pandemic, experts noted that Viral persistence has become one of the most consistent findings, with Different studies identifying SARS fragments or proteins in blood, gut tissue, and other organs long after acute infection. Here, the pattern is not uniform, which suggests that only a subset of patients harbor these reservoirs, but it is strong enough that many researchers now see persistent SARS as a central pillar of Long COVID biology rather than a fringe idea.

Evidence that hidden reservoirs drive symptoms

Finding viral remnants is one thing, proving they cause symptoms is another. That is where more targeted studies have started to fill in the gaps. In work summarized under the title Study Finds Persistent Infection Could Explain Long COVID, investigators at Brigham reported that Some People with a wide range of lingering symptoms had evidence of ongoing viral activity, while others with similar histories did not. Brigham researchers found people with persistent immune activation and viral markers were more likely to test positive for a COVID infection long after the acute phase, suggesting that reservoirs are not just biochemical curiosities but active drivers of disease.

Other teams have taken a broader view, looking at how these reservoirs might sit at the center of a web of inflammation, clotting problems, and nervous system disruption. A detailed analysis of patients with chronic fatigue, pain, or digestion issues concluded that Here, Viral persistence could help explain why Different organ systems are affected and why SARS infection seems to leave such a long shadow. If viral proteins are still nudging the immune system or damaging cells, then the symptoms are less a mystery and more a chronic infection problem that standard tests have been missing.

Hidden infections beyond COVID: EBV, TB and more

Even as evidence for persistent SARS-CoV-2 grows, another layer of complexity has emerged. Some researchers argue that Long COVID may be as much about other microbes as about the original virus. A sweeping review from Dec experts at Rutgers noted that 44 nations have experienced tenfold increases in at least 13 infectious diseases compared with pre-pandemic levels, a pattern they argue is hard to explain without considering how COVID has reshaped immunity and exposure. The most compelling evidence involves pathogens that were already in the body, lying dormant until the immune disruption of SARS-CoV-2 gave them an opening.

Respiratory specialists have zeroed in on Latent or concurrent infections that seem to flare in a subset of Long COVID patients. Reports describe how Latent viruses such as Epstein and Barr, along with tuberculosis, may drive persistent symptoms in people whose immune systems were weakened by COVID. In parallel, Dec analyses of microbiology data have highlighted that When these infections occur also matters, since Some pathogens that hit before or after SARS-CoV-2 can weaken defenses and set the stage for chronic illness, a pattern that has been reported in Long COVID cohorts.

Reactivation, immune dysfunction and the EBV clue

Among the non-COVID suspects, Epstein-Barr virus has drawn particular attention. EBV is nearly universal and usually quiet, but it is notorious for reactivating when the immune system is under stress. In Dec coverage of a major review, researchers described how Researchers studied existing reviews to map how EBV reactivation might exploit immune dysfunction after Covid, arguing that it could help explain fatigue, cognitive problems, and other hallmarks of Long COVID. Later work linked EBV reactivation to specific symptom clusters, suggesting that Another layer of infection may be shaping who develops which chronic complaints.

Clinicians on the front lines are seeing similar patterns. In a detailed conversation about Long COVID 2025, Unger and colleagues described how COVID appears to leave some patients with a weakened immune system that struggles to control latent viruses like Epstein-Barr virus, as well as other chronic infections. They emphasized that Unger has seen COVID patients whose symptoms only make sense when EBV and similar pathogens are brought into the picture, reinforcing the idea that Long COVID may often be a multi-pathogen syndrome rather than a single-virus aftermath.

Why the timing and scale of infections matter

If hidden infections are part of the story, timing becomes crucial. Immunologists have pointed out that the order in which pathogens hit can shape how the body responds, sometimes for years. Dec analyses of microbiology data stress that When infections occur also matters because Some pathogens that strike before SARS-CoV-2 can weaken the immune system, while others that arrive after COVID exploit the lingering dysfunction. In practice, that means two people with similar acute COVID cases might diverge sharply depending on whether they were already harboring EBV, tuberculosis, or other microbes that could be jolted awake.

The scale of the problem is sobering. The Dec review that highlighted One explanation they cite, called microbial reactivation, noted that 44 nations have seen tenfold increases in at least 13 infectious diseases compared with pre-pandemic levels, a pattern that may reflect both disrupted health systems and deeper immune shifts. The authors argue that understanding Long COVID will require looking beyond COVID itself, tracing how SARS-CoV-2 has reshaped the broader infectious landscape and how those changes feed back into chronic symptoms.

Clinical trials that treat Long COVID as an infection problem

As the infection hypothesis gains traction, it is starting to reshape treatment research. One of the clearest examples is a clinical trial at UCSF that is testing the antiviral ensitrelvir in patients with suspected viral reservoirs. The trial description notes that Persistent viral infection with viral reservoirs and detection of circulating spike protein after the initial illness are central to the study design, reflecting a belief that clearing residual SARS-CoV-2 could relieve symptoms. By directly targeting the virus rather than just managing inflammation or pain, the trial is a real-world test of whether hidden infection is more than a theory.

Other experimental therapies are following a similar logic. Infectious disease specialists have highlighted several Promising clinical trial efforts, including AER002, a long-acting human immunoglobulin being tested in patients with Long COVID, and other agents that aim to modulate immune responses that may be reacting to persistent viral antigens. In parallel, a separate study of a SARS-CoV-2 specific monoclonal antibody for Post-COVID conditions is enrolling patients whose symptoms last beyond the acute infection, randomizing them to receive the antibody or one dose of placebo, as described in the In some patients trial listing. Together, these efforts treat Long COVID less like a static injury and more like an active disease process that might be reversed.

Targeting the SARS-CoV-2 reservoir directly

Behind these trials sits a broader scientific push to map and attack viral reservoirs. A detailed review of the field argues that a growing body of evidence shows that SARS-CoV-2 can persist for months or years following COVID in a subset of individuals, and that targeting this reservoir may require combination approaches. The authors outline how careful tissue sampling, advanced imaging, and immune profiling could help identify where the virus hides, while antiviral drugs, monoclonal antibodies, and even vaccines might be used in tandem to flush it out.

For patients, this reservoir-focused strategy offers a more concrete path than vague promises of “supportive care.” If clinicians can show that SARS is still present in the gut, brain, or other organs, then they can justify aggressive treatment aimed at clearing it, much as they do for chronic hepatitis or HIV. The challenge is that standard tests were never designed to find low-level, tissue-based infection, which is why researchers are calling for new diagnostics and longitudinal assessments to track how viral load, immune markers, and symptoms move together over time as part of these potential combination approaches.

What a hidden-infection model means for patients and policy

For the millions living with Long COVID, the idea that hidden infections are at work is both daunting and hopeful. On one hand, it suggests that their symptoms are not psychosomatic or purely “post-viral,” but rooted in ongoing biological processes that can be measured. On the other, it implies that solving the problem will require more than rest and rehabilitation. Dec analyses from health security experts argue that Resource Links and large-scale study of Long COVID will be needed to untangle how Medical News and Net For millions of patients, persistent breathlessness, brain fog, and other symptoms may be tied to infections that standard care does not yet address.

Public health agencies will have to adapt as well. If Long COVID is partly a story of reactivated EBV, tuberculosis, and other microbes, then surveillance systems must track those pathogens alongside SARS-CoV-2. Dec reporting on a major review emphasized that Rebecca Whittaker and colleagues at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School argue that Yet, Covid can affect the brain, heart, lungs, and digestive system, but there are still no proven treatments because research has not fully accounted for hidden infections. If policymakers take that critique seriously, funding and guidelines may shift toward integrated care that screens for and treats multiple pathogens in Long COVID clinics rather than focusing on COVID alone.

More from MorningOverview